BOOKS

Survival of the nicest

Conn Welch

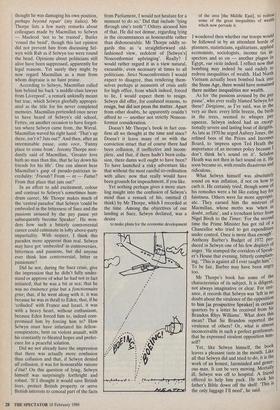

SELWYN LLOYD by D. R. Thorpe

Cape, £16, pp.504

It was one of the greatest moments of my years of Parliamentary reporting. It was at once hilarious and deeply touching. After a long and chequered career, full of unex- Pected promotions, muddles and unpre- dicted disasters, poor old Selwyn, dear old Selwyn had become in 1963 Sir Alec Douglas-Home's Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House. On 24 October he had to speak on the Address. Fred Willey interrupted to accuse him as Chancellor in 1961-2 of needlessly cutting education spending. Selwyn conceded that he'd had to contend with pressures on the economy and with the problem of resources avail- able. He testily countinued that public spending on education had actually risen in that year by £141m. Labour roared in unison, 'You got the sack!' — a reference to Macmillan's hideous night of the long knives, when so many prominent heads rolled, including Selwyn's. Mr Thorpe records Selwyn's retort as 'immediate'. I recall a typical moment of hesitation, a few urn's and er's, a short struggle with a sword slightly bent and rusty, hard thus to draw, to flash and flourish aloft. Nor could the words which eventually emerged be de- scribed as memorable, if they did not remain indelibly in the memory. 'W- whatever may have happened', Selwyn blurted out triumphantly, `I-I-I am back again now!'

All sides of the House exploded in a long roar of affection and amusement. Selwyn was indeed 'back again', not for the first hole, nor for the last. He had yet another resurrection ahead of him as Speaker of the House, an appointment greeted by him (privately and wryly, maybe, yet with a grain of truth) with relief that he `no longer had to pretend to be a Tory'. If he wasn't a Tory or not wholly a Tory, what on earth Was he? Mr Thorpe has several shots at telling us, without complete success. The resultant confusion may quite accurately reflect the normal state of Selwyn's mind. On one occasion Mr Thorpe describes Selwyn as 'an old-style Gladstonian Free Trade Liberal'. Really? For this old-style free trader left the Liberal party, for which he had stood at Macclesfield in 1929, precisely because he favoured an emergen- cy tariff in 1931.

When this old-style Gladstonian was Chancellor, moreover, dirigisme was all the rage. Concepts like planning, mostly French inspired, incomes policies, guiding lights, Nickies and Neddies, pay pauses and wage restraint obsessed Selwyn and his master, Macmillan, as also the Treasury mandarins of the day. (Only the great Sir Frank Lee seems to have stood out against the corporate trend, to emphasise the importance of competition in economic management.) I doubt if Mr Gladstone would have approved of these prestigious panaceas, though some of them in various forms still infest what is laughingly called Labour's economic thinking. Another shot from Mr Thorpe seems to me nearer the mark. He defines Selwyn as 'in modern parlance a Tory "Wet".' His attitudes on many social issues (notably capital punish- ment) were decidedly liberal'. His attitude to inflation, however, was decidedly un- Wet.

Mr Thorpe's dust-jacket excitedly crows about revealing many unexpected facets of Selwyn's personality, about new light shed on various episodes and about widely received opinions countered by hitherto unknown details. Yet the new light falls on much that remains obscure, confused and incomprehensible, and more widely re- ceived opinions and expected facets of Selwyn's personality are confirmed than are corrected. No one, to be sure, ever thought of Selwyn as an aesthete. Yet his philistinism is here revealed as almost boundless, if endearingly unpretentious. He liked Westerns, films about the Spanish Main and Robin Hood, Georgette Heyer (why not, indeed?) and South Pacific. Invited by the Soviet Ambassador to the `prestigious' (Mr Thorpe's word) closing night of The Cherry Orchard, Selwyn said that he'd sat through Uncle Vanya and that was all that heroism could require. As Mr Thorpe puts it, 'he loved the beautiful, but with economy' — yes, with great economy.

Selwyn does emerge as more quirky and amusing than I'd expected, much given to little jokes. He was apparently the real author of Alec Douglas-Home's most famous crack. Harold Wilson had jeered about half a century of democratic advance being arrested by a 14th Earl. 'As far as the 14th Earl is concerned', Douglas-Home dryly commented, 'I suppose Mr Wilson, when you come to think of it, is the 14th Mr Wilson'. Selwyn also emerges as kind, decent, unenvious, devoid of rancour and spite, uncensorious, to opponents warm and courteous, forgiving, generous and convivial — 'his hospitality was one of cases, not bottles', not bad for one with a strict teetotal Nonconformist background. None of these facets is exactly unexpected, except in sheer extent: he really must have been an extraordinarily nice man. Richard Crossman once declared that no sort of impeachment about Suez or the like would wash, 'because everyone liked Selwyn'.

A widely received opinion which is confirmed is, alas, the ruthless treachery and duplicity of Harold Macmillan. It is the more confirmed because Mr Thorpe, like Selwyn himself, is devoid of partisan bile. On the whole, he lets the facts speak for themselves, though even he, when speak- ing of Selwyn's sacking, cannot suppress words like shameful, unworthy and un- grateful. Selwyn's own restraint about the matter was prodigious. He recalled Mac- millan's various kindnesses to him. He expressed sorrow for him, 'because I thought he was damaging his own position, perhaps beyond repair' (my italics). Mr Thorpe lists a few nasty remarks about colleagues made by Macmillan to Selwyn — Macleod 'not to be trusted', Butler `round the bend', though this last opinion did not prevent him from discussing Sel- wyn with Rab as if Selwyn too were round the bend. Opinions about politicians still alive have been suppressed, apparently for legal reasons. Yet surely they might by now regard Macmillan as a man from whom dispraise is no faint praise.

According to Selwyn, Macmillan called him behind his back 'a middle-class lawyer from Liverpool', a remark unkindly meant but true, which Selwyn gleefully appropri- ated as the title for his never completed memoirs. Macmillan pretended once never to have heard of Selwyn's old school, Fettes, on another occasion to have forgot- ten where Selwyn came from, the Wirral. Macmillan waved his right hand: 'That's up there, isn't it? Juts out?' And then, after an interminable pause, sotto voce, 'Funny place to come from'. Jeremy Thorpe mor- dantly said of Macmillan, 'Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life'. One can almost hear Macmillan's gasp of pseudo-patrician in- credulity: 'Friends? From — er — Fattus? From that place that juts out?'

In an effort to add excitement, colour and contrast to Selwyn's sometimes hum- drum career, Mr Thorpe makes much of the 'central paradox' that Selwyn 'could be embroiled in the bitterness of Suez and the passions aroused by the pay pause yet subsequently become Speaker'. He won- ders how such a bitterly controversial career could culminate in lofty above-party impartiality. With respect, I think this paradox more apparent than real. Selwyn may have got 'embroiled' in controversies, bitterness and passions, but did anyone ever think him controversial, bitter or passionate?

Did he not, during the Suez crisis, give the impression that he didn't fully under- stand or approve of what he had not in fact initiated; that he was a bit at sea; that he was no eminence grise but a fonctionnaire grise; that, if he went along with it, it was because he was in thrall to Eden; that, if he 'colluded' with France and Israel, it was with a heavy heart, without enthusiasm, because Eden forced him to, indeed com- promised him by forcing him to? How Selwyn must have infuriated his fellow- conspirators, bent on violent assault, with his constantly re-bleated hopes and prefer- ence for a peaceful solution.

Did we not already have the impression that there was actually more confusion than collusion and that, if Selwyn denied all collusion, it was for honourable raisons d'etat? On this question of lying, Selwyn himself was surprisingly forthright and robust. 'If I thought it would save British lives, protect British property or serve British interests to conceal part of the facts from Parliament, I would not hesitate for a moment to do so.' Did that include 'lying through one's teeth'? Others accused him of that. He did not demur, regarding lying in the circumstances as honourable rather than dishonourable. Mr Thorpe oddly re- gards this as 'a straightforward old- fashioned view, redolent of [Selwyn's] Nonconformist upbringing'. Really? I would rather regard it as a view natural, excusable, even necessary at times to all politicians. Strict Nonconformists I would expect to disagree, thus rendering them- selves perhaps at moments of crisis unfit for high office, from which indeed, forced to lie, I would expect them to resign. Selwyn did offer, for confused reasons, to resign, but did not press the matter. Apart from other doubts, he apparently couldn't afford to — another not strictly Noncon- formist consideration.

Doesn't Mr Thorpe's book in fact con- firm all we thought at the time and since? Doesn't it leave many of us with the conviction intact that of course there had been collusion, if ineffective and incom- plete, and that, if there hadn't been collu- sion, there damn well ought to have been? To have launched a risky adventure like that without the most careful co-ordination with allies: now that really would have been grounds for impeachment, if you like.

Yet nothing perhaps gives a more start- ling insight into the confusion of Selwyn's mind than a remark of his, omitted (I think) by Mr Thorpe, which I recorded at the time. Among the objectives of our landing at Suez, Selwyn declared, was a desire

to make plans for the economic development of the area [the Middle East], to redress some of the great inequalities of wealth which now pervade it.

I wondered then whether our troops would be followed in by an attendant horde of planners, statisticians, egalitarians, applied economists, sociologists, income tax in- spectors and so on — another plague in Egypt, vae victis indeed. I reflect now that bombing may indeed be said rudely to redress inequalities of wealth. Had North Vietnam actually been bombed back into the Stone Age, there would have remained there neither inequalities nor wealth. As for 'the passions aroused by the pay pause', who ever really blamed Selwyn for these? Dirigisme, as I've said, was in the very air then: every little breeze, the birds in the trees, seemed to whisper pay squeeze. Selwyn indeed had an excep- tionally severe and lasting bout of dirigitis. As late as 1970 he urged Aubrey Jones, the refined • boss of the Prices and Incomes Board, to 'impress upon Ted Heath the importance of an incomes policy because I don't think he's sound on it'. Selsdon Heath was not then in fact sound on it. He soon became so, with results disastrous and ridiculous.

What Selwyn himself was absolutely sound on was inflation, if not on how to curb it. He certainly tried, though some of his remedies were a bit like eating hay for faintness. Others were far more appropri- ate. They earned him the mistrust of Macmillan, whose motto was 'when in doubt, reflate', and a trenchant letter from Nigel Birch to the Times: 'For the second time the Prime Minister has got rid of a Chancellor who tried to get expenditure under control. Once is more than enough . Anthony Barber's Budget of 1972 pro- duced in Selwyn one of his few displays of anger. 'He stumped the corridors of Speak- er's House that evening, bitterly complain- ing, "This is against all I ever taught him • To be fair, Barber may have been angrY too.

Mr Thorpe's book has some of the characteristics of its subject. It is diligent, not always imaginative or clear. For inst- ance, it records that Selwyn was 'left in no doubt about the virulence of the opposition to him [as prospective Speaker] in certain quarters by a letter he received from Sir Brandon Rhys Williams'. What does this mean? That Sir Brandon reported the virulence of others? Or, what is almost inconceivable in such a perfect gentleman, that he expressed virulent opposition him- self? Yet, like Selwyn himself, the book leaves a pleasant taste in the mouth. Like all that Selwyn did and tried to do, it is the work of an honest, fairminded and gener- ous man. It can be very moving. Mortally ill, Selwyn was off to hospital. A friend offered to help him pack. He took his father's Bible down off the shelf: 'This is the only luggage I'll need', he said.

Previous page

Previous page