An outstanding novelist and publisher

John Henshall

HOBSON'S ISLAND by Stefan Themerson

Faber, £11.95, pp. 196

When Stefan Themerson died in Lon- don last September, aged 77, the event was hardly major news, even in literary circles. The death of his wife and partner of 54 years, the artist Franciszka Themerson, in July, had received even less attention. These would have been occasions for sadness anyway, but the case of Stefan Themerson had its own peculiar poignan- cy. He was an outstanding writer, of whom most people who might have been in- terested had simply never heard.

Perverse as it may sound, this is just how Themerson seems to have intended it should be. He was born at Plock, near Warsaw, and studied physics and architecture in the Polish capital; he met Franciszka, and began to make a name as a screen reviewer and producer, with his wife, of experimental films. The Themersons moved to Paris in 1937, and when war came, he joined the Polish forces in France, and she came to England. In 1942, he joined her here; what was to prove perhaps the best-kept literary- artistic secret in post-war Europe was set up and ready for business.

While the war continued, Themerson wrote for the Polish-language weekly, Nowa Polska, and his poetry was published by the old Poetry-London imprint, which also issued his first novel, Bayamus and the Theatre of Semantic Poetry (1949). Themerson had publishing ambitions of his own, however, and in 1948 started the Gaberbocchus Press, which he ran for 31 years, first in Chelsea, then in Maida Vale. With Franciszka as principal illustrator- designer, he created the leading British avant-garde imprint of its day.

Themerson published all his and Fran- ciszka's copious output through Gaberboc- chus, deliberately eschewing the big firms of the mainstream publishing market. His other authors included the novelist Oswell Blakeston, the Irish poet George Bucha- nan, Christian-Dietrich Grabbe, a still- neglected German playwright, Kurt Schwitters, about whom Themerson wrote Kurt Schwitters in England (1958), C. H. Sisson, Stevie Smith, Anatol Stern and Kenneth Tynan.

There was also Bertrand Russell, who was so impressed by Bayamus and the debut of a singular talent, that he wrote to congratulate Themerson on having written a novel 'as mad as the world'. Themerson was the first to publish the Ubu plays of Alfred Jarry in English, and he also issued a superbly presented edition of Apolli- naire's Lyrical Ideograms, (1968), the French poet's `calligrammes' or word- picture poems. Themerson also published Raymond Queneau (with whom he himself has been compared). Queneau's Exercises in Style (published here in 1958) was described as 'ninety-nine different views of a minor brawl on a Paris omnibus' fitting, for the extraordinary Gaberboc- chus list.

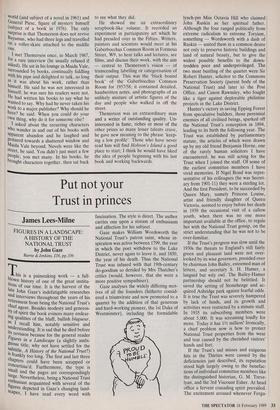

In 1979, Themerson sold his interest in Stefan Themerson, photographed by Francois Lagarde, London, 1977

Gaberbocchus to the Amsterdam imprint, De Harmonie. It was through them, entire- ly by chance, that he came to be published by Faber. In 1985, De Harmonie issued a novel entitled Euclides was een ezel (Euclid was an Ass). This was spotted by a Dutch- speaker with Faber connections and subse- quently appeared here in 1986 as The Mystery of the Sardine (Faber paperback £3.95). The Dutch title is that of a section of the book about a child mathematics prodigy. So pleased were Faber with their 75- year-old discovery that they planned to reissue some of Themerson's Gaberboc- chus novels, including Professor Mmaa's Lecture (1953) and Tom Harris (1967). Now Themerson is dead, it remains to be seen if this will happen, but, meanwhile, Faber have published what turned out to be Themerson's last novel, Hobson's Is- land.

As with The Mystery of the Sardine, this new book weaves several plots into one, and is in many ways a continuation of the bizarre roman fleuve which is Themerson's whole output, as much as any kind of `story' in itself. To appreciate it, it is necessary to remember that its author was probably as interested in philosophy as fiction (he wrote several philosophical books) and in logic in particular. The novel is ostensibly about a deposed African head of state who is smuggled to a 'secret' island in the Channel where, for decades, suitably anonymous Swiss bankers have been con- ducting an experiment with the one resi- dent family, to see how much tourgeoisi- fication' a human group needs in the middle of nowhere.

Themerson contrives to turn this into a consideration of eschatology (eerily enough, it has the feel of a book whose author knew it was his last), the 'genera- tion gap', the motives of government and those governed, and his theories on human nature. He tries throughout to demons- trate his proposition (put to the British Association in 1982) that human nature is essentially benign, with violence the pro- duct of 'imposed' ideas and culture. It is a marvellously impressive book by a first- class intellect; it is also unlikely to make the best-seller lists. Its predecessor, The Mystery of the Sardine, is a similarly arcane work, which begins as a cross between a political thriller and a comedy of international manners set in London, Warsaw and Majorca. The final section, a piece of riveting intensity, concerns an alien being Who returns home in a flash, after spending 74 years on earth (during which he has always been 34, to the puzzlement of mere humans around him) fruitlessly seeking 'the mystery of the sardine', or how the sardine-canners of Portugal pack their products (not that We meet any Portuguese sardine-canners In the book). Both these last two books feature Themersonian stock characters like Cardinal Polatuo, the oldest man in the world (and subject of a novel in 1961) and General Piesc, figure of mystery himself (subject of a book in 1976). The only surprise is that Themerson does not revive Bayamus, who had three legs and travelled on a roller-skate attached to the middle one.

I met Themerson once, in March 1987, for a rare interview (he usually refused if asked). He sat in his lounge in Maida Vale, surrounded by books, continually fiddling with his pipe and delighted to talk, so long as it was about his work, rather than himself. He said he was not interested in himself; he was sure his readers were not. He had written his books to say what he wanted to say. Why had he never taken his work to a major publisher? Why should he have? he said. When you could do your own thing, why do it for someone else? I asked about the recurring characters who wander in and out of his books with apparent abandon and he laughed and gestured towards a shuttered window and Maida Vale beyond. Novels were like the street, he said. You didn't just meet a few People, you met many. In his books, he brought characters together, then sat back to see what they did.

He showed me an extraordinary scrapbook-like volume. It recorded an experiment in participatory art which he had presided over in the Fifties. Writers, painters and scientists would meet at his Gaberbocchus Common Room in Formosa Street, W9, to hear talks and lectures, see films, and discuss their work, with the aim — central to Themerson's vision — of transcending labelling or categorisation of their output. This was the 'black bound book' of the Gaberbocchus Common Room for 1957/58; it contained detailed, handwritten notes, and photographs of an unlikely mixture of artistic figures of the day and people who walked in off the street.

Themerson was an extraordinary man and a writer of outstanding quality. Un- interested in fame, riches or most of the other prizes so many lesser talents crave, he gave new meaning to the phrase 'keep- ing a low profile'. Those who have never read him will find Hobson's Island a good place to start; I think he would have liked the idea of people beginning with his last book and working backwards.

Previous page

Previous page