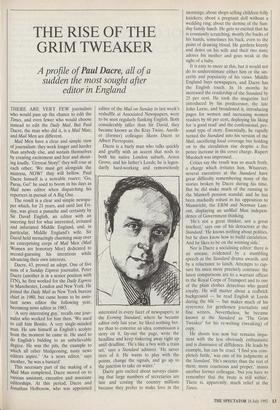

THE RISE OF THE GRIM TWEAKER

A profile of Paul Dacre, all of a

sudden the most sought after editor in England

THERE ARE VERY FEW journalists who would pass up the chance to edit the Times, and even fewer who would choose instead to edit the Daily Mail. But Paul Dacre, the man who did it, is a Mail Man; and Mail Men are different.

Mail Men have a clear and simple view of journalism: they work longer and harder than anybody else, and sustain themselves by creating excitement and fear and shout- ing loudly. `Grrreat Story!' they will roar at each other; 'We must get alongside the mistress, NOW!' they will bellow. Paul Dacre himself is a noteable roarer: 'Go, Paras, Go!' he used to boom in his days as Mail news editor when dispatching his reporters in pursuit of A Big One.

The result is a clear and simple newspa- per which, for 21 years, and until last Fri- day, was given a panache and certainty by Sir David English, an editor with an unerring feel for what interested, irritated and infuriated Middle England, and, in particular, Middle England's wife. Sir David held menacingly charming sway over an enterprising corps of Mail Men (Mail Women are honorary Men) dedicated to second-guessing his intentions while advancing their own interests.

Dacre, 43, proved an adept. One of five sons of a Sunday Express journalist, Peter Dacre (another is in a senior position with ITN), he first worked for the Daily Express in Manchester, London and New York. He Joined the Daily Mail as New York bureau chief in 1980, but came home to be assis- tant news editor the following year, becoming news editor in 1983.

'A very interesting guy,' recalls one jour- nalist who worked for him then. 'We used to call him Benito. A very single-minded man. He saw himself as English's acolyte from the moment he came in. He used to do English's bidding to an unbelievable degree. He was the pits, the example to Which all other bludgeoning, nasty news editors aspire.' As a news editor,' says another, 'he was a bastard'.

This necessary part of the making of a Mail Man completed, Dacre moved on to various assistant, executive and associate editorships. At this period, Dacre and Jonathan Holborow, who was appointed editor of the Mail on Sunday in last week's reshuffle at Associated Newspapers, were to be seen regularly flanking English. Both considerably taller than Sir David, they became known as the ICray Twins. Anoth- er (former) colleague likens Dacre to Albert Pierrepoint.

Dacre is a burly man who talks quickly and gruffly with an accent that nods to both his native London suburb, Amos Grove, and his father's Leeds; he is legen- darily hard-working and remorselessly

interested in every facet of newspapers; at the Evening Standard, where he became editor only last year, he liked nothing bet- ter than to conceive an idea, commission a story on it, lay-out the page, write the headline and keep tinkering away right up until deadline. 'He's like a boy with a train set,' says a Standard admirer. 'He never tires of it. He wants to play with the points, change the signals, and go up to the junction to take on water.'

Dacre gets excited about surveys claim- ing that large numbers of secretaries are late and costing the country millions because they prefer to make love in the mornings; about shops selling children frilly knickers; about a pregnant doll without a wedding ring; about the demise of the Sun- day family lunch. He gets so excited that he is constantly scratching, mostly the backs of his hands, sometimes his back, even to the point of drawing blood. He gardens keenly and dotes on his wife and their two sons; adores his mother and goes weak at the sight of a baby.

It is easy to sneer at this, but it would not do to underestimate either him or the sin- cerity and popularity of his views. Middle England buys newspapers, and Dacre has the English touch. In 16 months he increased the readership of the Standard by 25 per cent. He took the magazine feel introduced by his predecessor, the late John Leese, and broadened it, introducing " pages for women and increasing women readers by 60 per cent, deploying his liking for 'a good read' and the confessional, per- sonal type of story. Essentially, he rapidly turned the Standard into his version of the Mail, sacrificing local coverage but holding on to the circulation rise despite a five pence increase in the cover charge. Rupert Murdoch was impressed.

Critics say the result was so much froth, a charge which irritates him. Whatever, several executives at the Standard have great difficulty remembering many of the stories broken by Dacre during his time. But he did make much of the running in the Maxwell pension scandal; and he has been markedly robust in his opposition to Maastricht, the ERM and Norman Lam- ont, displaying an unMail Man indepen- dence of Government thinking.

'He's not a great thinker, not a great intellect,' says one of his detractors at the Standard. 'He knows nothing about politics, but he does know how to build circulation. And he likes to be on the winning side.'

Nor is Dacre a socialising editor: there is an unease, evidenced by a stumbling speech at the Standard drama awards, and by a reluctance to lunch. Attempts to cap- ture his mien more precisely continue: the latest comparisons are to a warrant officer in the Royal Corps of Transport and to one of the plain clothes detectives who guard royalty. He will mutter about a redbrick background — he read English at Leeds during the 60s — but makes much of his reverence for gentlemen journalists and fine writers. Nevertheless, he became known at the Standard as 'The Grim Tweaker' for his re-writing (tweaking) of copy.

He shouts less now but remains impa- tient with the less obviously enthusiastic and is dismissive of diffidence. He leads by example, but can be cruel. find you com- pletely futile,' was one of his judgments at the Standard. 'He's sweeter than the rest of them, more courteous and proper,' insists another former colleague, 'but you have to remember that the brute is still within'. There is, apparently, much relief at the Times.

Previous page

Previous page