What North-South divide?

Allan Massie

Edinburgh A t first it was going to be an election .L-A.in which Scotland decisively marked off its difference from the rest of Britain, rejected the Thatcherism which the South endorsed, and so emphasised the famous North-South divide. Then more sensational rumours teased the fancy. The Labour vote was collapsing. Everyone said so. At least Conservative, Alliance and Nationalist spokesmen did. No doubt this was a bit like the massed choirs whistling in the wind. It gave a boost to what had been a surprisingly low-keyed campaign. But then normality re-asserted itself. The hungry sheep were flocking back to the Labour fold. On the day of the election a MORI poll in the Scotsman put Labour at 41 per cent, only half a point down from their May 1979 position.

In fact none of these forecasts worked out. The trend in Scotland was not marked- ly different overall from the trend in England and Wales. The Labour vote did not of course disentegrate as it did in That- cherland — nobody had really thought that possible — but neither did Labour hold its ground. In Scotland as in the South the on- ly party to gain in popular support was the Alliance. Here it actually increased its number of seats.

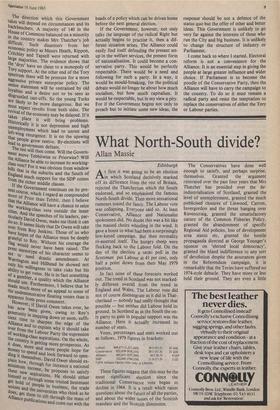

Votes, percentages and seats worked out as follows, 1979 figures in brackets:

Labour 969,475 (1,211,445) 34.3 (41.5) 41 (44)

Conservative 822,654 (916,155) 29.1 (31.3) 21 (22)

Alliance 692,631 (255,395) 24.5 (8.7) 8 (3).

SNP 322,045 (504,259) 11.8 (17.3) 2 (2) "1979 Alliance figures refer only to Liberals.

These figures suggest that this may be the most significant election since the traditional Conservative vote began to decline in 1964. It is a result which raises questions about the future of all the parties, and about the wider issues of the Scottish mandate and the Scottish dimension.

The Conservatives have done well enough to satisfy, and perhaps surprise, themselves. Granted the argument reiterated over the past four years that Mrs Thatcher has presided over the de- industrialisation of Scotland, granted the level of unemployment, granted the much publicised closures of Linwood, Carron, Invergordon and the threat hanging over Ravenscraig, granted the unsatisfactory nature of the Common Fisheries Policy, granted the abandonment of specific Regional Aid policies, loss of development area status etc, granted the hostile propaganda directed at George Younger's squeeze on 'elected local democracy', granted the bland indifference to any sort of devolution despite the assurances given in the Referendum campaign, it is remarkable that the Tories have suffered no 1974-style debacle. They have more or less held their ground. They are even a little

more secure. Whereas in 1979 they regained four seats with majorities of less than a thousand, there are now only two, Albert McQuarrie's Banff and Buchan and (rather surprisingly) Lord James Douglas- Hamilton's Edinburgh West, that are quite so endangered. It is true that there is only one seat (Gordon, won by the Liberals) where the Tories are breathing down the victor's neck; but on the other hand there is nowhere that Labour looks capable of mounting a challenge in a Conservative seat. With the certainty of four years in power, and the possibility of some sort of economic revival, the Tories can look forward with modest optimism. The frightful prospect of the evaporation of the Tory vote that gave them nightmares in the Seventies has receded.

That is significant. It is significant too that Labour has shown its inability to damage a Conservative government that has presided over a major recession. If it can't win Conservative seats now, it may never do so again. Labour may not be in headlong decline — it is still after all the biggest party in Scotland and the one in whose favour the electoral system currently works — but it is certainly in retreat. Its performance in Scotland may bear a super- ficial resemblance to the Tories' victory in Britain. Like Mrs Thatcher Labour has won a considerable majority of seats on a minority of votes; but the differences are more marked than the similarities.

Vfirst, Labour's share of the vote is very much smaller in Scotland than the Con- servatives' in Britain. It has actually lost Scot- tish seats in this election. Second, whereas the Tories' main appeal is directed to the economically progressive parts of the coun- try, Labour looks to those in decline. It is a matter of momentum. In Scotland Labour is now confined to Strathclyde and the in- dustrial seats of the Central Belt. Outside that area, the party holds only one seat in Dundee and one in Aberdeen. More remarkably, over much of Scotland Labour has disappeared as an electoral force. There were 17 seats in the Highlands, Borders, Tayside and Grampian where Labour came either third or fourth; in nine in fact they were fourth. In those 17 seats the party's total vote was 67,346, some 40,000 fewer than the SNP who themselves had a disappointing election. Even in Edin- burgh Labour was pushed into third place in three seats by the Alliance candidate. In fact, outside Strathclyde and the Central Belt, Labour's performance here was every bit as dismal as in the South of England. That should be remembered whenever there is parrot-talk of the North-South divide; we have our own geographical division here too. Labour is now pinned in its industrial (or de-industrialised) citadel, still im- pregnable there, but hardly now possessing a fifth column beyond.

Doubtless Scottish Labour suffered from difficulties at British level, from left-wing extremism in the Manifesto and from the failure of Mr Foot to appeal to any but committed Labour supporters. Never- theless over the last four years Scottish Labour has been in much better heart than the party in the South, suffered far fewer debilitating splits, is less evidently decayed; yet contrived to lose a quarter of a million votes and three seats.

The real beneficiaries have been the Alliance parties. They alone have increased their vote, very substantially too. They have eight members of Parliament whereas previously they had six, one of whom, the SDP defector Dickson Mabon, had to switch to a new seat (which he lost). Moreover they finished second to Labour in 18 seats and second to the Conservatives in ten. Certainly they weren't challenging closely in many of these; especially in Glasgow Labour continues to pile up huge majorities (more than 50 per cent of votes cast in eight of Glasgow's eleven consti- tuencies, where it should be said polls were generally low). Nevertheless the message is clear. Both the Conservative and Labour parties are abandoning the middle ground; neither is mounting much of a challenge in the other's strongholds. As in England, a way through the middle exists for the Alliance parties.

It does begin to look, in both countries, as if social changes are detaching an in- creasing number of voters from automatic allegiance to one party or the other. In par- ticular the continuing decline here of the Labour vote, falling below a million for the first time since before the war, suggests that wherever voting has become an expression of opinion rather than a matter of habit, reflex action, or class loyalty, where fron- tiers have become fluid, the electorate lives in Debatable Land and will be won over by character, party ethos and policies. The old arrogant notion that votes really belong to Labour or Conservative and are only lent to any other party has been exploded. The only dynamism in this election in Scotland came from the Alliance parties. No doubt they were helped by the presence of the par- ty leaders in Scottish seats, but that hardly begins to explain their advance.

In fact their movement seems to have taken over, and carried on, the SNP surge

`Stand back, my dear, I think it may be some political animal.'

Spectator 18 June 1983 of the Seventies. (Together the Alliance and the Nationalists topped the million mark). The SNP themselves lost ground, though still prominent where they had previously done best, in Tayside and around the Moray Firth. Gordon Wilson had a good win in Dundee. Douglas Henderson came close to recovering the seat he lost to Albert McQuarrie last time. They came second in Perth and Kinross, Tayside North, Moray and Angus East without however quite threatening to win seats they had formerly held, and in which they had done better in 1979. Not helped by their internal disputes, the SNP have lost all semblance of representing 'tine idee en marche'. The success of the Alliance — the parties who want to 'change the system', with the Liberals at least being completely committed to Home Rule — is likely to draw voters in in- creasing numbers from the Nationalists; Alliance candidates wiped the floor with them in the Highlands and Borders (except Galloway) and in Gordon, the old West Aberdeenshire seat. It is hard to see the SNP recovering. The part of their suPPort which was as much an expression of dislike for Conservative and Labour as of a wish for an independent Scotland will find a home in the Alliance parties.

The mention of Home Rule brings us to

the question of the Tories' mandate. The cry goes up that they haven't got one.Not only did they receive less than a third of the votes, but they are also the only partY not committed to a Scottish Assembly. (Th,e, depth of Labour's commitment is still doubtful despite the fact that Robin Cook apparently discovered on election night that the road to Damascus ran through his Liv- ingstone New Town constituency). Yet, for ntwoothstnoglid but reasons, hot air.

'No Mandate' cry is

theFilrasstt, tphaerlsiamituaetnior.n cheasonrg'te cyhnatingnegdersion cde his team had no difficulty in governing Scotland then. The machinery of Scottish government does not require a majority of Scottish seats. The suggestion being floated that the opposition parties might combine — none of them of course having an !rt" dividual mandate in the form of a majority of the popular vote — is not a horse likely to run, if only because the Alliance, to ad- vance, must train its guns on Labour.

More important is the answer given by

Malcolm Rifkind on television. Seventy ot the 72 Scottish constituencies, he pointed out, elected a member representing one of the United Kingdom parties. The Scots had a clear opportunity to choose candidates who would separate them from Englaned. and an English Tory ascendancy; we t,n jected tthhaet cuhnanitceed. By preferringto remai to play the game by Westminster we agree

rules. Tories should the This is not to say that the

not be more sensitive than they have been to Scottish opinion. In fact, the rise of tr e Alliance parties representing a force capable of winning votes from the Tories a:. Labour can't, will itself exercise that sort t influence on the Conservatives.

Previous page

Previous page