GET OUT OF JAIL FREE: TO MAKE A BILLION

Robert Philip reveals the bottom line of professional boxing:

Mike Tyson's conviction for rape was a smart career move, and now the ex-champion is set to reap the benefits

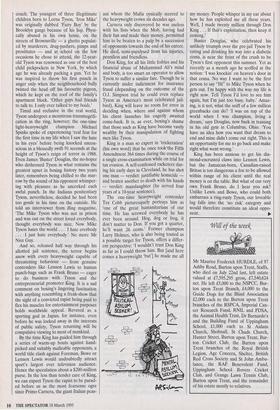

ON 25 MARCH, the gates to the Indiana Youth Correction Center will swing open and prisoner 922335 (aka Mike Tyson) will issue forth into the sudden glare of the television arc lights; free at last, free at last as some commentator will almost certainly feel moved to pronounce, free at last to resume his life of legalised violence.

An estimated 5,000 journalists, photogra- phers and cameramen will be in attendance to record the moment, for this is no ordi- nary hoodlum being released after serving three years of a six-year sen- tence for raping a beauty pageant contestant in his hotel bedroom. Assuming his talent for inflicting grievous bodily harm on opponents inside the boxing ring is undiminished by 37 months locked away in the slammer, inmate 922335 is poised to become the wealthi- est athlete in sporting history.

In his previous existence as heavyweight champion of the world, Tyson earned $150 mil- lion, allowing him to buy huge tracts of New York real estate, a collection of cars, including two Rolls-Royces, a Jaguar, an Aston Martin, a Lagonda, a Ferrari, a couple of Bentleys and the pre-requisite Lam- borghini; he also favoured a full-length white mink coat, loafers by Gucci, watches by Rolex and chunks of gold by Tiffany's, while displaying a rapacious thirst for Dom Perignon and beautiful women such as the singer Whit- ney Houston and the star of the Cosby Show, Lisa Bonet.

'One hundred and fifty million?' scoffs Don King, boxing's notorious Mr Fixit (more of whom later). 'You can multiply that tenfold second time around. Mike Tyson will be sport's first billionaire. He's gonna be bigger than Jack Nicklaus, bigger than Ali, bigger than the Pope.'

King's calculating enthusiasm is shared by many; not since Muhammad Ali was 'pardoned' a quarter of a century ago, after being stripped of the heavyweight title fol- lowing his refusal to serve in the United States Army during the Vietnam war, has boxing awaited the return of a champion warrior with such slavering anticipation. For just as Ali made millions for everyone with whom he exchanged punches — not to mention his motley entourage of promot- ers, aides, managers, trainers, advisers and Black Muslim teachers, all of whom syphoned off their various percentages so Tyson's emergence from behind bars will mean vast riches for others by associa- tion.

At present, the fractured heavyweight division can paw ade three different 'title- holders' — Riddick Bowe, Oliver McCall and 46-year-old George Foreman — but no matter what the World Boxing Council (WBC), the World Boxing Association (WBA), the World Boxing Organisation (WBO), or any other alphabet-spaghetti self-interest group would have us believe, it is Tyson who remains the undisputed Peo- ple's Champion, the natural heir in a noble pugilistic line stretching down through Ali to Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis and Jack Johnson, all the way back to the great prize-fighters of old.

Traditionally regarded as the 'richest prize in sport', the heavyweight champi- onship will become a global industry the instant our prisoner from Cell Block H pulls on gloves and raises his dukes (the odd unpaid prison spat notwithstanding) for the first time since 1991. Bowe, who cheerfully and accurately describes Tyson as 'a commodity', received a mere $600,000 for bruising his fists on the chin and ribs of Britain's Her- bie Hide in Las Vegas last weekend. Contrast that with a possible contest involving Tyson and Foreman, who lost the title to Ali in the famous 'Rumble in the Jungle' in Zaire 21 years ago, only to regain the WBC version as a grandfather last winter, which is estimated to be worth at least $100 mil- lion for each fighter. No great surprise, then, that Frank Bruno and Lennox Lewis are among a host of applicants eager to trade blows with this soon-to-be-ex-con who was reckoned to be 'the most dan- gerous unarmed man in the world' when he became the youngest ever heavyweight champion as a 20-year-old in 1986.

Only in the brutal world of boxing could a conviction for rape be seen as a smart career move, but there can be no denying that at the time of his trial in February 1992 Tyson's mystique was on the wane; from 1986 to February 1990, he had been invincible, an old-fash- ioned —some would say primeval — fight- ing machine who enjoyed boasting: 'Every punch I throw has bad intentions. I always try to catch them on the tip of the nose . . . to try and push the bone into their brain.'

That propensity for violence becomes immediately understandable when you place Tyson — gently — on the psychiatric couch. The youngest of three illegitimate children born to Loma Tyson, 'Iron Mike' was originally dubbed 'Fairy Boy' by the Brooklyn gangs because of his lisp. Physi- cally abused in his own home, on the streets of Brownsville — a ghetto populat- ed by murderers, drug-pushers, pimps and prostitutes — and at school on the few occasions he chose to attend, the 12-year- old Tyson was renowned as one of the best child pickpockets in New York, by which age he was already packing a gun. Yet he was inspired to throw his first punch in anger only when the neighbourhood bully twisted the head off his favourite pigeon, which he kept on the roof of the family's apartment block. 'Other guys had friends to talk to. I only ever talked to my boids: Timid and reclusive in the real world, Tyson undergoes a monstrous transmogrifi- cation in the ring, however; the one-time light-heavyweight champion Michael Spinks spoke of experiencing 'real fear for the first time in my life when I saw the hate in his eyes' before being knocked uncon- scious in a blessedly swift 91 seconds at the height of Tyson's reign of terror in 1988. Even James 'Buster' Douglas, the no-hoper who dethroned Tyson in what remains the greatest upset in boxing history two years later, remembers being chilled to the mar- row by the sound of his opponent whimper- ing with pleasure as he uncorked each awful punch. In the Indiana penitentiary Tyson, nevertheless, decided he had been too gentle in his time on the outside. He told an interviewer from Ring magazine, `The Mike Tyson who was not in prison and was out on the street loved everybody, thought everybody was nice. Now Mike Tyson hates the world . . . I hate everbody . . . I just hate everybody.' No more Mr Nice Guy.

And so, released half way through his allotted jail sentence, the terror begins anew with every heavyweight capable of threatening behaviour — from genuine contenders like Lennox Lewis to human punch-bags such as Frank Bruno — eager to do business with Tyson and the entrepreneurial promoter King. It is a sad comment on boxing's lingering fascination with anything resembling a freak-show that the sight of a convicted rapist being paid to flex his muscles for entertainment purposes holds worldwide appeal. Revered as a sporting god in Japan, for instance, even before he was locked away in the interests of public safety, Tyson returning will be compulsive viewing to most of mankind. By the time King has guided him through a series of warm-up bouts against hand- picked and suitably malleable opponents, a world title clash against Foreman, Bowe or Lennox Lewis would undoubtedly attract sport's largest ever television audience. Hence the speculation about a $200-million purse. In the less than tender care of King, we can expect Tyson the rapist to be parad- ed before us as the most fearsome ogre since Primo Camera, the giant Italian peas- ant whom the Mafia cynically steered to the heavyweight crown six decades ago.

Camera only discovered he was useless with his fists when the Mob, having had their fun and made their money, permitted him to be beaten to a pulp by a succession of opponents towards the end of his career. He died, semi-paralysed from his injuries, penniless and friendless.

Don King, for all his little foibles and his financial abuse of Muhammad Ali's mind and body, is too smart an operator to allow Tyson to suffer a similar fate. Though he is currently under indictment for insurance fraud (depending on the outcome of the O.J. Simpson trial he could even replace Tyson as America's most celebrated jail- bird), King will leave no room for error in deciding when, where and against whom his client launches his eagerly awaited come-back. It is, as ever, boxing's shame that those such as King have become vastly wealthy by their manipulation of fighting men like Tyson. King is a man so expert in `trickeration' (his own word) that he once took•the Fifth Amendment 364 times during the course of a single cross-examination while on trial for tax evasion. A self-confessed racketeer dur- ing his early days in Cleveland, he has shot one man — verdict: justifiable homicide and beaten another to death with his hands — verdict: manslaughter (he served four years of a 10-year sentence). The one-time heavyweight contender Tex Cobb picturesquely portrays him as `one of the great humanitarians of our time. He has screwed everybody he has ever been around. Hog, dog or frog, it don't matter to Don. If you got a quarter, he'll want 26 cents.' Former champion Larry Holmes, who is also being touted as a possible target for Tyson, offers a differ- ent perspective: 'I wouldn't trust Don King as far as I could throw him. But [and here comes a heavyweight 'but] he made me all my money. People whisper in my ear about how he has exploited me all these years. Well, I made twenty million through Don King . . . If that's exploitation, then keep it coming.'

Buster Douglas, who celebrated his unlikely triumph over the pre-jail Tyson by eating and drinking his way into a diabetic coma, is near the front of the crush to be Tyson's first opponent this summer. Yet as recently as a month ago he scoffed at the notion: 'I was knockin' on heaven's door in that coma. No way I want to be the first person to say "Hi" to Mike Tyson when he gets out. I'm happy with the way my life is right now. Tell Tyson I'd love to see him again, but I'm just too busy, baby.' Amaz- ing, is it not, what the sniff of a few million greenbacks can do? 'I was on top of the world when I was champion, living a dream,' says Douglas, now back in training in his old gym in Columbus, Ohio. 'You have an idea how you want that dream to end and mine didn't come out right. This is an opportunity for me to go back and make right what went wrong.'

King has been anxious to get his dia- mond-encrusted claws into Lennox Lewis, but the Jamaican-born, Canadian-raised Briton is too dangerous a foe to be allowed within range of his client until the real money is on the table. But what of our very own Frank Bruno, do I hear you ask? Unlike Lewis and Bowe, who could both embarrass a ring-rusty Tyson, our loveable lug falls into the 'no risk' category and would therefore constitute an ideal oppo- nent. A three-time loser in world title bouts, Bruno does look like a champion. He just does not fight like one. Muscled and mag- nificent, one British writer once compared him to Michelangelo's David. 'Only Bruno's not as fast,' came a dismissive American riposte.

Tyson will be a lethally angry man when the bell sounds to resume his career, har- bouring a grudge against the world. His opponent will assume the identity of the prison guard he despises above all others. `Pantomime' Frank v. Indiana State Prison- er 922335? The only question is, could Tyson's hands take the punishment?

Meanwhile, the cash register rings louder than the ambulance's siren.

Robert Philip is a columnist with the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page