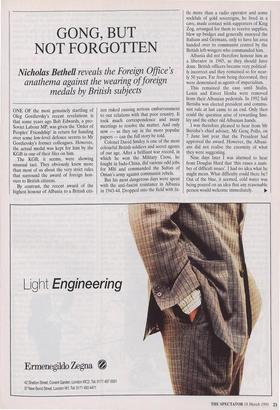

GONG, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

Nicholas Bethell reveals the Foreign Office's

anathema against the wearing of foreign medals by British subjects

ONE OF the most genuinely startling of Oleg Gordievsky's recent revelations is that some years ago Bob Edwards, a pro- Soviet Labour MP, was given the 'Order of Peoples' Friendship' in return for handing over some low-level defence secrets to Mr Gordievsky's former colleagues. However, the actual medal was kept for him by the KGB in one of their files on him.

The KGB, it seems, were showing unusual tact. They obviously knew more than most of us about the very strict rules that surround the award of foreign hon- ours to British citizens.

By contrast, the recent award of the highest honour of Albania to a British citi- zen risked causing serious embarrassment to our relations with that poor country. It took much correspondence and many meetings to resolve the matter. And only now — as they say in the more popular papers — can the full story be told. Colonel David Smiley is one of the most colourful British soldiers and secret agents of our age. After a brilliant war record, in which he won the Military Cross, he fought in Indo-China, did various odd jobs for MI6 and commanded the Sultan of Oman's army against communist rebels. But his most dangerous days were spent with the anti-fascist resistance in Albania in 1943-44. Dropped into the field with lit- tie more than a radio operator and some sockfuls of gold sovereigns, he lived in a cave, made contact with supporters of King Zog, arranged for them to receive supplies, blew up bridges and generally annoyed the Italians and Germans, only to have his area handed over to communist control by the British left-wingers who commanded him.

Albania did not therefore honour him as a liberator in 1945, as they should have done. British officers became very political- ly incorrect and they remained so for near- ly 50 years. Far from being decorated, they were demonised as agents of imperialism.

This remained the case until Stalin, Lenin and Enver Hoxha were removed from their Albanian pedestals. In 1992 Sali Berisha was elected president and commu- nist rule at last came to an end. Only then could the question arise of rewarding Smi- ley and the other old Albanian hands.

I was therefore pleased to hear from Mr Berisha's chief adviser, Mr Genc Pollo, on 7 June last year that the President had approved the award. However, the Albani- ans did not realise the enormity of what they were suggesting.

Nine days later I was alarmed to hear from Douglas Hurd that 'this raises a num- ber of difficult issues'. I had no idea what he might mean. What difficulty could there be? Out of the blue, it seemed, cold water was being poured on an idea that any reasonable person would welcome immediately. The Vice-Marshal of the Diplomatic Corps then said to me, 'The award and wearing of foreign medals is a very compli- cated matter.' It had never occurred to me. Many British ex-soldiers wear their Croix de Guerre with pride and I once saw the chest of Sir Freddie Bennett MP shining like a Christmas tree through the reflected glory of a dozen foreign stars. Why should the brave Colonel Smiley be deprived?

Slowly the secret emerged. It seems that in the late 16th century the Pope had the temerity to make Lord Arundell of War- dour a Count of the Holy Roman Empire. Queen Elizabeth I was very angry. These were days when the Pope was the enemy, and Roman Catholics who kept the faith were seen as disloyal.

She sent the unfortunate Lord Arundell to the Fleet prison for two months and banished him from court. 'I will not have my dogs wearing foreign collars, nor my sheep branded with another man's mark,' she said. From then on it has been the rule that a British subject must obtain permis- sion from the monarch before wearing any foreign medal. And today, in such matters, the Queen acts on Foreign Office advice.

The FCO were quick to reassure me that it is not accepting a foreign medal without permission that is the problem. Any medal may be accepted 'as a souvenir or keepsake'. It is wearing it that 'raises difficult issues'. It is not a criminal offence. An Englishman will not, nowadays, be sent to prison for wearing his Legion d'Hon- neur without permission, but he will be, according to Lord Cranborne, committing `a discourtesy to the sovereign', even if the medal is worn on a civilian suit.

The FCO rule also says — I do not know why — that permission can only be given if the offer of the foreign medal occurs less than five years after the events in question. The effect of this rule is to cut out those British soldiers who helped the peoples of Eastern Europe against Hitler. Communist governments did not reward them when they had the chance, and now that they are gone it is too late, because of the FCO's rule. For instance, last year the Polish government struck a medal to com- memorate the 50th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising. They wanted to award it to British airmen who dropped supplies in August 1944. Permission has still not been given by London, although according to the Polish embassy 'many British veterans wear the medal anyway'.

The Soviet Union played down the con- tribution made to their war effort by the famous Arctic convoys. It rankled with the Royal Navy and Merchant Navy veterans of the convoys that, for political reasons, they were given no British or Soviet cam- paign medal.

Then in 1985 the Soviets struck a medal to celebrate the 10th anniversary of victo- ry. They also announced, since it was the early days of Mr Gorbachev and glasnost, that the medal would be available to British seamen from the Russian convoys.

`We were delighted,' says Robert Allan, chairman of the veterans' body. `If was the first official recognition given to the con- voys by any government. We were given the medal by the Soviet ambassador and we wore it at British Legion functions and on Remembrance Sunday. Then suddenly we were told that we weren't allowed to.'

In April 1993 the junior minister Vis- count St Davids made the stark announce- ment, 'The Russian commemorative medal can be accepted as a souvenir only and is not to be worn.' The House of Lords was very angry. The members of the Russian Convoys Club were even more angry and their anger was in no way assuaged by news that British soldiers were receiving and wear- ing, with permission, European Communi- ty medals for 21-day tours of duty in Croatia. They felt that their efforts on the convoys were more important than the Foreign Office's rules and so, totally ignoring the words of Viscount St Davids, they carried on wearing their medals.

Meanwhile a campaign to legalise them continued. Sir Ludovic Kennedy, a veteran of the Convoy, says, 'I spoke to the Foreign Office, but all I got was a lot of guff about how the Queen might be offended. Eventu- ally it was sorted out, I think by the Duke of Edinburgh.'

On 4 January last year the London Gazette announced that the Queen had given permission for the Russian medal to be worn. It was, said Lady Chalker, 'a very special circumstance' that 'justified excep- tional treatment'.

This was the difficulty that Douglas Hurd was referring to in his conversation with me over Colonel Smiley's medal. An exception had already been made, over the convoys, and it would be wrong to allow the Albani- ans to make another so soon.

He had a meeting with other depart- ments, then wrote to me outlining the com- promise that he had in mind: 'One solution might be for the Albanian government to present letters of citation .. , This could be done for example at a formal ceremony, banquet or reception.'

And this is how it turned out. At the end of last year, Smiley was invited to Albania and presented with a certificate that con- ferred on him 'The Order of the Freedom of Albania — First Class'.

This specially devised Order has, from the Foreign Office's point of view, one very important merit. It is a piece of paper. And a piece of paper cannot be worn. So it falls within their rules.

Smiley, who already holds the Order of the Sword (Sweden) and the Order of Jebel Akhdar (Oman) as well as a host of other honours, British and foreign, remains sanguine. 'It is more like a university diplo- ma than a medal,' he says. 'I've never had one like that. I must frame it and hang it on the wall.'

Lord Bethell is a Commander of the Order of Merit (Poland).

Previous page

Previous page