The Secret Sacrament

wATE, INTO WINE. By E. S. Drawer. (John Murray, 25s.) MIN, in his Apologia, records how deeply impressed he was nglican days by Wiseman's quotation of Securtis iudicat iii te .rariiin and how large was the influence of this quotation Pers tailing him into leaving the Anglican for the Roman athoii ,Q4cierse Church. It must, I think, have occurred to many io a that, whatever the claims of the Catholic Church N..wina;reater universality than the Church of England, ft have r I was nevertheless invoking a principle which might

or him dangerous. consequences. For the Christian

religion at man Utt any form has only been accepted by a small proportion t ind and over a tiny period. It would seem then, at first !"'iversalat, whatever the positive beliefs to which consensus may lead us, it must, at any rate, forbid us from accept- 1)1(1)gsstelluenclaim of the Christian or any other religion to be the 1r of unique truth. t Vet comparative religion shows that the results of, an appeal " cons the conenslis universalis are not really negative. They show us, on !Amon lrarY, that there is a remarkable general agreement in beliefs t belief among mankind—an agreement not merely in such Vstern Is that in a Supreme Being or in some future life and of rewards and punishments, which might have been 1:re4ciled nnity, bY natural reason, but also in a belief in such things as a %rile n. a mysterious reverence for virginity, a faith that there is reaso tethod of obtaining the assistance of God—beliefs the or which is by no means easily apparent. Even debased

and satanic beliefs, such as the belief in human sacrifice, appear as perversions of purer beliefs more generally held. And these general beliefs of the earlier religions are continued and re- produced in Christianity. Yet Christianity differs from them in that its claims are historical whereas theirs are mythological. The other religions say, 'This is the sort of way that things must be. Otherwise they do not make sense.' Christianity gives the assurance of revelation and says, `Yes, this is the sort of way that things are. It has been revealed to us.'

To these conclusions either of two interpretations can be given. Either we can say, 'There is a universal religion of which Christianity. is one of the forms. Where the other religions tacked on the eternal stories to certain mythological persons, the Christians tacked them on to certain historical or pseudo-historical persons.' Or we can say, 'The Divine plan has two stages. GOd first gave to men these vague and shadowy ideas and yearnings which they could follow out for themselves, and then, when Man had come himself to feel the necessity for something more, when the Incarnation had been in a manner, if in a very imperfect manner, demanded, the demand was at last granted. The other , religions were a part of the prteparatio evangelica for the unique religion.' Which interpretation we accept depends upon whether we decide that the Christian historical claims are acceptable or not.

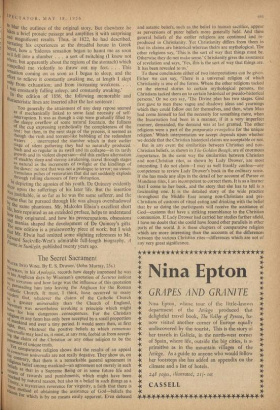

But in any event the similarities between Christian and non- Christian beliefs, as shown in The Golden ough, are of enormous .importance. In the same way the similarities between Christian and non-Christian rites, as shown by Lady Drower, are most interesting. I do not claim—I may as well frankly confess—any competence to review Lady Drower's book in the ordinary sense. If she has made any slips in the detail of her account of Parsee or Mandan rites, I am incompetent to correct them. It is as a learner. that I come to her book, and the story that she has to tell is a fascinating one. It is the detailed story of the wide practice throughout the Middle East among non-Christians and pre- Christians of customs of ritual eating and drinking with the belief that by so doing the participants will receive the assistance of God—customs that have a striking resemblance to the Christian communion. If Lady Drower had carried her studies farther afield, I have no doubt that she could have found other parallels in other parts of the world. it is these chapters of comparative religion which are more interesting than the accounts of the differences between the various Christian rites—differences which are not of any very great significance.

, l9 5 ! It is very interesting to know how the Parsees do these thing It is by no means so easy to understand what purpose they thin'

to be served by doing them. It is easy, of course, to say 'fertilill rite.' Primitive man observes, of course, that the condition obtaining a crop is that the seed be first buried in the earth. Of he observes that the condition of his own physical vigour is tb$1 he, from time to time, eats and drinks things. But it is not to see why he should think that his crops will be the better becal0 he enacts some sort of pantomime of the process of nature; clt why, if he eats and drinks according to a special rite, he shell believe that God will give him an especial assistance over 011,7 above the normal accession of strength of the food and dri°l The Christian, of course, believes that the Christian sacratlia confers grace because he believes that he has the divine Walls.: that it will do so. It is hard to see what reason any beli ve cr lot a non-revealed religion can have for a faith in the efli acY his sacraments. To one who accepts the truth of the Christian story, Chriso t/ death and resurrection become inevitably the central eN ea history : the one divine event to and from which the whole ( ;realts° A moves, and, therefore, in so far as there is a parallelism betvie,„'" the story of Christ and the processes of nature, it is not 11' Christian story which is the symbol of the fertility rite, but 1,11,1 fertility rite which is the symbol of the Christian story. The bur' and resurrection of the seed is the prefigurement of the burial resurrection of Christ rather than the reverse. It is a pity that Lady Drower, while describing the comi nuai° rites—Christian and non-Christian—of the East, did not them with the rites of the West. Christ gave His command 01411 disciples to eat and drink in communion, but there was no ) divi" command as to the detail of the way in which this comint# COP should be held. Therefore naturally enough the early Christians followed in detail the general customs of that part of° world for the details of their ceremony, and thus it is rea: sol0 enough that there should be considerable similarity betweell tiled Eastern Christian Mass and the Masiqta and Yasna of Parsecs 'd Mandmans. But what is interesting is the mark of contrast bet all such Eastern rites, Christian or non-Christian, and the cust°'

.00 of the Western world. Throughout the Eastern world the mYs'

it oa$1 are always performed in secret out of sight of the congreg:a as, in the Eastern Church, behind the eiconostasis. It is the 01,4 mark of Western religion that its mysteries should be perforni.i before the public eye. The reminder of older custom still su' re fle in the Roman Mass, where the priest says Introibo ad (dab 4 'I will go into the altar of God.' He is, in fact, standing beforeL visible altar. The words `go into' are in modern times meanilly

„(00 They are, of course, relics of an older time, when he stood u`' a screen which divided the congregation from the altar.

CHRISTOPHER

Previous page

Previous page