Exhibitions 2

Seurat (Grand Palais, Paris, till 11 August)

Getting to the point

Elizabeth Mortimer

The Seurat retrospective exhibition currently being held in Paris at the Grand Palais is the occasion of much breast-beat- ing. This is the first full appraisal of his work in his native city since his death at the early age of 31 a century ago, and the sad fact is that three of his four major composi- tions left France in the mid-1920s, unwant- ed by the art establishment and unap- preciated by the general public. These three, now among his best-known works, have not been able to travel, and have only a spectral presence here in the form of life- size black-and-white photographs. It is odd to see all the preparatory oil sketches and drawings without their culmination, like a banquet without the guest of honour. In spite of this, however, Seurat's genius is apparent in the subtlety and originality of the works on show, and the optical effects of the divison of colour, for which he is most famous, seem the least of his achieve- ments.

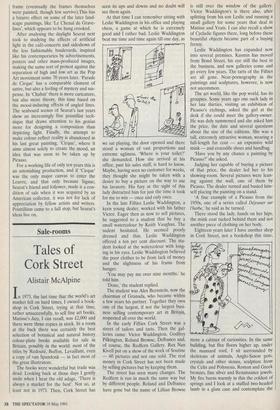

The missing works, all huge in scale and monumental in conception, were designat- Seurat's 'Le aineur, 1883-84, drawing in conte crayon ed by Seurat as toiles de lutte, and had the character of manifestos. They were mile- stones on his way to the creation of a new classicism to fit the modern scientific age, replacing that of the academic tradition which had prevailed since the days of Poussin and which still dominated the pub- lic art of the late 19th century, and also the teaching of the Beaux-Arts. The paintings in question are 'Bathers, Asnieres' (National Gallery), 'Sunday on the Island of the Grande Jatte' (Chicago, Art Institute) and `Poseuses' (Merion, Barnes Foundation), completed in 1884, 1886 and 1888. They show an increasingly consistent attempt at organising the surface in accor- dance with the scientific principles of optics, now generally known as pointillism, although Seurat called it 'chromoluminar- ism', a term that not surprisingly failed to catch on. Until now we have seen the grand statement but have not been party to the discussions leading up to it, and it is fascin- tating to see in this exhibition the workings of the artist's mind revealed.

It starts with a series of remarkable drawings. The first few are conventionally shaded academy studies of the male nude or after casts of antique sculpture, with the beginnings of an interest in describing fore- shortening through outline. However, Seurat abandoned this approach when he left the Beaux-Arts after one year in the undistinguished atelier of Henri Lehmann. He did a year's military service, then, aged 21, set himself up in a studio with his friend Arnan Jean and embarked on an indepen- dent career. The new drawings are extraor- dinarily original and powerful. They are done in black conte crayon, a kind of soft chalk, on rough-grained, off-white paper, whose luminous surface is left bare where the light falls, or lightly touched so that the grain shows through for the mid-tones. Most are of a single figure, often a work- man or a passer-by seen from behind or in full profile, carefully positioned within the rectangle of the sheet against a neutral background in such a way that their per- sonality or their mood dominates the com- position, though their faces are almost always averted. The silhouette is reduced to its essentials, the pose expressive with- out using gestures. The drawings are dark with a crepuscular gloom, the forms struck rather than moulded by light. Edges are accentuated, the shaded side against a halo of light, the lit one against dense shadow. There are also a number of landscapes, equally minimal in content, but with the same withdrawn and subdued atmosphere, all astonishingly evocative.

The paintings are in complete contrast to this, though they share a preoccupation with edges, where one colour impinges on another. Loosely brushed in a variety of strokes, they first take up the themes favoured by Millet and Courbet, the coun- tryside and its outdoor labourers. Then the scene shifts to the semi-industrial Parisian banlieue on the banks of the Seine, much loved by the Impressionists, and Seurat's treatment of water, recalls that of Renoir and Monet. He paints a number of oil- sketches which he calls croquetons, often on small panels of varnished wood, but although they are apparently spontaneous they also show great care in their composi- tion. From these scenes by the river at Asnieres the idea of the 'Bathers' evolves, founded on direct observation but also including the fruit of Seurat's studies of optics, notably Ogden Rood's Scientific Theory of Colours, together with an ele- ment of social comment. The resulting pic- ture, two metres by three, was rejected by the Salon and exhibited with the newly founded Groupe des Artistes Independ- ents. The stages leading up to it show Seurat's systematic method of preparation, from the first free sketches through a clos- er observation of the setting to the posed studies of the figures made in his studio. But nothing quite prepares us for the fin- ished painting, which is unlike anything seen before. The fact that it is not there (for reasons of fragility) emphasises the gaping chasm between the sum of the parts and the whole, and the creative leap of the artist's imagination. The preparation of the 'Grande Jatte' is still more thorough. By now Seurat's stern ambitions for reforming art have become clearer: 'They see poetry in what I do; no, I apply my method, and that is all.' He pro- poses to underpin the Impressionists' intu- itive understanding of light with recent sci- entific discoveries in the field, and by stripping away accidental elements from his figures to arrive at a new archetype which will be the enduring essence of modern man. The resulting masterpiece fails to demonstrate the colour theory because it is not possible to do so in pigment. In any case the principle is not consistently applied, but the myriad small touches give the surface a vibrant atmospheric richness, which Seurat tests and elaborates in the preliminary sketches. Among the most intriguing are those that show the setting before the people arrive. The recession is plotted by the alternation of light and shad- ow under the trees, exactly in the manner of classical landscape painting, and the grass is a tissue of complementary colours. The figures, when they take their places, confirm the mastery of expressive form apparent in the earliest drawings. Furthermore, a brilliantly observed econo- my of means allows the combined effect of their scale and the angle of the shadows to suggest the undulations of the turf. These are the immediate ancestors of the stylised forms of Art Deco.

Around this time Seurat became inter- ested in the framing of his pictures, and many of them are surrounded by pointillist rims in complementary colours, designed to bridge the transition from the image to the frame (eventually the frames themselves were painted, though few survive).This has a bizarre effect on some of the later land- scape paintings, like `Le Chenal de Grave- lines', which appears to be hung crooked.

After analysing the daylight Seurat next took to studying the effects of artificial light in the café-concerts and sideshows of the less fashionable boulevards, inspired like his contemporaries by advertisements, posters and other mass-produced images, making the same sort of protest against the separation of high and low art as the Pop Art movement some 70 years later. 'Parade de Cirque' has a comparable element of satire, but also a feeling of mystery and sus- pense. In `Chahue there is more caricature, but also more theory, this time based on the mood-inducing effects of angled lines. The seaboard scenes of Seurat's last years show an increasingly fine pointillist tech- nique that draws attention to his genius more for designing a composition than depicting light. Finally, the attempt to make colour reflect reality is abandoned in his last great painting, 'Cirque', where it aims almost solely to create the mood, an idea that was soon to be taken up by Picasso.

For a working life of only ten years this is an astonishing production, and if 'Cirque' was the only major canvas to enter the Louvre, and that only because Signac, Seurat's friend and follower, made it a con- dition of sale when it was acquired by an American collector, it was not for lack of appreciation by fellow artists and writers. Pointillism came to a full stop, but Seurat's ideas live on.

Previous page

Previous page