THE CHANCELLOR MAKES HIS MARK

Helmut Kohl will reject monetary union, Andrew Gimson believes, because he does not want to be the one to ditch the deutschmark

Berlin BISMARCK SAID he 'always found the word "Europe" on the lips of those politi- cians who wanted something from other powers which they dared not demand in their own names'.

Over a century later, one longs for another German statesman who will dispel the noxious clouds of hypocrisy, self- deception and boredom that hover over the word 'Europe'. Instead, we are obliged to cope, in Chancellor Helmut Kohl, with one of the greatest advocates of Europe the world has ever known.

He says so few things that translate well into English, and looks so ungainly in pho- tographs, that one is tempted to write him off as an even greater Euro-bore than the rest of the German governing class. Until a few years ago, many German commenta- tors themselves made the mistake of under- estimating him, perhaps because he gave no sign of valuing them.

But Kohl is in fact a genius, and nowhere more so than in his brilliant exploitation of the word 'Europe', which he has used to win the support of two seemingly irrecon- cilable kinds of German: those who want to extend German power, and those who would rather bind or extinguish it.

The horrors of the Nazi period created, by reaction, a self-abnegating type of Ger- man idealist, for whom nothing is more retrogressive than any hint of nationalism. Many of them are to be found in German politics, including the Chancellor's own party. They are splendid, upright, often youngish people, with good brains, but also with the disquieting air of naivety found in the Oxford Group or at a Billy Graham prayer meeting. When you ask them why they are in politics, they reply, `To build Europe!'

But it would be a gross libel on the Ger- man political class to suggest they are all like that. Many of them have not thrown off the dependable old passions of greed, racism and nationalism.

The contrast is doubtless overdrawn. Most German politicians probably have mixed motives. But now that the astonish- ingly wide political consensus which saw the Maastricht Treaty through to ratific- tion in Germany is breaking down, one can see it was all along composed of two utterly incompatible schools of thought.,

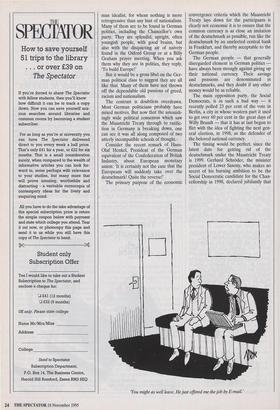

Consider the recent remark of Hans- Olaf Henkel, President of the German equivalent of the Confederation of British Industry, about European monetary union: 'It is certainly not the case that the Europeans will suddenly take over the deutschmark! Quite the reverse!'

The primary purpose of the economic convergence criteria which the Maastricht Treaty lays down for the participants is clearly not economic it is to ensure that the common currency is as close an imitation of the deutschmark as possible, run like the deutschmark by an unelected central bank in Frankfurt, and thereby acceptable to the German people.

The German people — that generally disregarded element in German politics have always been strongly against giving up their national currency. Their savings and pensions are denominated in deutschmarks, and they doubt if any other money would be as reliable.

The main opposition party, the Social Democrats, is in such a bad way — it recently polled 23 per cent of the vote in Berlin, a city in whose western part it used to get over 60 per cent in the great days of Willy Brandt — that it has at last begun to flirt with the idea of fighting the next gen- eral election, in 1998, as the defender of the beloved national currency.

The timing would be perfect, since the latest date for getting rid of the deutschmark under the Maastricht Treaty is 1999. Gerhard SchrOder, the minister president of Lower Saxony, who makes no secret of his burning ambition to be the Social Democratic candidate for the Chan- cellorship in 1998, declared jubilantly that `You might as well leave. He just offered me the job by E-mail.' the party, which seems to have no distinc- tive policies left, had once again found a `national issue' in the deutschmark.

He argued that the enormous transfer payments from north to south Europe which monetary union would require `would overtax the German economy'. Germany could take on 'no additional commitment in Europe', because it is already bearing the huge burden of trans- fer payments from west to east Germany required to finance the German monetary union of 1990. The deutschmark, he added, is one of the Germans' identity symbols, and we don't have so many of those'.

The present leader of the Social Democrats, a crashingly dull man called Rudolf Scharping, fought and lost against Kohl last year and has since ridden out wave upon wave of unrest within his own ranks. The bearded Scharping, whose main hobby is bicycling, is described by another of his rivals for the leadership, the person- able Heide Simonis, minister president of Schleswig-Holstein, as an `autisf.

His ability to create a feeling of unease among those around him is so enormous, it compels one's reluctant admiration. Surely politics is not quite the right line for him? Surely he understands that he's got to go? But by the time this article appears he will probably have survived another spate of backstabbings at this week's party conference in Mannheim.

Scharping tried, with characteristic clumsiness, to guard his flank against Schroder by saying the Germans would certainly not give up the deutschmark `because of any old idea'. But this exposed Scharping's other flank to an onslaught from his party's large contingent of True Believers.

There could scarcely be a truer German Social Democrat European than Klaus Hansch, the chillingly dedicated President of European Parliament, who announced in Brussels that economic and monetary union was a completely unsuitable subject for electioneering. 'One begins to burn the timbers of one's own house simply in order to heat the electoral soup,' he declared. Hansch says a common currency is in the true political and economic interests of Germany. The former Social Democrat Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, who employs his declining years writing articles for Die Zeit, agrees. He contends that without a common currency the deutschmark will soon dominate the whole of Europe, creat- ing 'fear and envy' in Germany's neigh- bours and leading to the formation of an anti-German alliance.

Kohl has been leader of the Christian Democrats since 1973 and Chancellor since 1982, but a recent poll of Christian Democrat voters suggested that only 36 per cent of them are in favour of a com- mon currency. Yet enquiries at his office after the last election confirmed that his great project is European union. He aspires to make the process of union 'irre- versible', brushes aside the objections of his economic advisers, who have always had cold feet, and says it is a question of war and peace. He treats the Bundesbank, which produces a stream of cogent objec- tions, like a windy group of general staff officers who don't realise the attack is sure to succeed.

But Kohl also has a far better feel for public opinion than most German politi- cians, and in the end he will act pragmati- cally. As his own backbenchers say, he is much too crafty to let himself be manoeu- vred into a 1998 election where he is the one trying to ditch the deutschmark. If past form is anything to go by, he will preserve a statesmanlike silence until it is absolutely certain which way the wind is blowing and the cries of distress from his own side have become desperate. Then the great man will declare that the princi- ple of monetary union is more important than the timetable, will remark (in tones of regret) that almost every other Euro- pean country is not yet ready for it, and will postpone the starting date. German politicians of all shades have already sug- gested doing this. An expert on these matters says now is the moment to buy German bond futures for the year 2000, which currently offer a substantially higher rate of interest than will be obtainable once the postponement has been announced. Postponement most likely means the death of monetary union. But year by year, the Germans need it less, because they are less afraid of being German. In 1989-90, East Germany was taken over by West Germany, but the influence of the easterners within reunit- ed Germany is growing more and more apparent. Day by day, they help dissipate the petit bourgeois inhibitions of the Bonn Republic. So too does the end of the struggle against communism. So too does the passing of the 50th anniversary of the end of the war.

The last Allied troops have marched away from the once and future capital, Berlin: the culmination of the process in which Germany regained its independent, sovereign status by the paradoxical means of swearing its undying commitment to supranational institutions, primarily the European Union and Nato. The country itself is more often referred to as Germany, less often as the Federal Republic. The German army is getting ready to operate around the globe.

This swift psychological change is infinitely more important than all the tech- nical arguments for and against monetary union which fill the serious newspapers. If he really tries, Chancellor Kohl can bully the central bankers into creating a common European currency, but what even he, the pre-eminent European statesman, cannot do is bully the German people into accepting it.

Previous page

Previous page