ARTS

Dance

The state of the Lake

Giannandrea Poesio

Aithony Dowell's production of Swan Lake for the Royal Ballet, which had its premiere in 1987, is still causing discontent among many ballet-goers. Yet, far from being radically innovative, Dowell's first aim was to revert to an idealised 'original' version, trimming off the numerous addi- tions introduced over the past 100 years.

Considered the embodiment of classical theatrical dancing, Swan Lake is, historical- ly speaking, a problematic ballet. The stan- dard versions of the work performed worldwide derive mainly from the 1895 production, created in St Petersburg by the French-born ballet-master Marius Petipa — the 'ballet genius' to whom works such as Don Quixote, La Bayadere, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker are credited — in collaboration with Lev Ivanov, one of the most innovative chore- ographers of the time.

Arguably considered by many as the defini- tive 'original' Swan Lake (the ballet had been unsuccessfully premiered in 1877 in Moscow), the 1895 pro- duction was recon- structed in 1934 by Nicholas Sergueev, Petipa's regisseur, for the Vic Wells Ballet in London — a reason let-goers consider Swan Lake exclusive to their cultural heritage. Although the authenticity of the Sergueev staging has never been questioned or assessed in full, a comparative analysis of the available sources reveals that there were substantial discrepancies between this production and its St Petersburg predeces- sor.

Neither the 1895 nor the 1934 staging, however, stood the test of time. The dra- matic content of the ballet and its score inspired a myriad of choreographic and dramatic changes; also, a constant updating was required to make the ballet accessible and acceptable through the years. In most cases, these additions have contributed sig- nificantly to the survival of the work, often becoming an integral part of its choreo- graphic tradition.

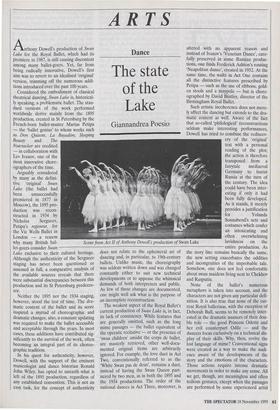

In his quest for authenticity, however, Dowell, with the support of the eminent musicologist and dance historian Ronald John Wiley, has opted to unearth what is left of the 1895 production, regardless of any established convention. This is not an easy task, for the concept of authenticity why many British bal- Scene from Act II of Anthony Dowell's production of Swan Lake does not relate to the ephemeral art of dancing and, in particular, to 19th-century ballets. Unlike music, the choreography was seldom written down and was changed constantly either to suit new technical developments or to appease the whimsical demands of both interpreters and public. As few of these changes are documented, one might well ask what is the purpose of an incomplete reconstruction.

The weakest aspect of the Royal Ballet's current production of Swan Lake is, in fact, its lack of consistency. While features that are generally omitted, such as the long mime passages — the ballet equivalent of the operatic recitative — or the presence of `swan children' amidst the corps de ballet, are masterly retrieved, other well-docu- mented original items are arbitrarily ignored. For example, the love duet in Act Two, conventionally referred to as the `White Swan pas de deux', remains a duet, instead of having the Swan Queen part- nered by two men, as in both the 1895 and the 1934 productions. The order of the national dances in Act Three, moreover, is altered with no apparent reason and instead of Ivanov's 'Venetian Dance', care- fully preserved in some Russian produc- tions, one finds Frederick Ashton's rousing `Neapolitan dance', created in 1952. At the same time, the waltz in Act One contains all the distinctive features prescribed by Petipa — such as the use of ribbons, gold- en stools and a maypole — but is chore- ographed by David Bintley, director of the Birmingham Royal Ballet.

None of the ballet's numerous metaphors is taken into account, and the characters are not given any particular defi- nition. It is also true that none of the cur- rent Royal ballerinas, with the exception of Deborah Bull, seems to be remotely inter- ested in the dramatic nuances of their dou- ble role — the good Princess Odette and her evil counterpart Odile — and the dancers focus exclusively on a technical dis- play of their skills. Why, then, revive the lost language of mime? Conventional signs were created as a way to make the audi- ence aware of the developments of the story and the emotions of the characters. Those actions require intense dramatic movements in order to make any sense. All we get, though, are meaningless and often tedious gestures, except when the passages are performed by some experienced artist such as Sandra Conley, who is superb as the Queen Mother.

Male dancers in this production, howev- er, seem to get more involved with the characters they portray — Irek Mukhame- dov, for example, as a troubled Prince Siegfried — probably because they are not given many chances; in this version of the ballet, the Prince is merely a supporting character. In the previous Royal Ballet's production, Rudolph Nureyev's solo at the end of Act One might have been a blatant example of artistic egotism as well as a whimsical interpolation, but it helped us to believe in the hero and, to a certain extent, in the entire story.

Giannandrea Poesio is the new dance critic of The Spectator.

Previous page

Previous page