Exhibitions

Turner Prize Shortlist (Tate Gallery, 3 December)

Love him or loathe him ...

Martin Gayford

Iwent to see the Tamer Prize Shortlist exhibition the day that Damien Hirst's dead cattle went on view. Somehow, it didn't seem worth looking at the show until then. After all, Hirst is the epitome of the Turner Prize — or what it has lat- terly come to stand for — and the pickled fauna in glass-tanks are the essence of Hirst. Without them, this little display would have been Hamlet without the Prince. This exhibit — 'Mother and Child, Divid- ed' to give it its proper title — of course consists of a cow and a calf, both neatly sliced from head to tail and arranged in four tanks. It had been withheld by the Tate Gallery for reinforcement of the glass walls of the tanks — which in itself is an interesting proof that this work of Hirst's belongs to two modish categories: danger- ous art and provocative art. That is, the piece is likely to encourage attacks from anti-avant-garde art vandals (who often turn out to be artists of another type), and, if molested, would deluge the public with formaldehyde.

`Mother and Child, Divided' is also a paradigm example of the kind of Turner Prize-ish artefact which prompts people to ask themselves the question: But is it art?' This is understandable. It is, however, the wrong question — if only because it leaves the questioner highly vulnerable to antago- nists who pounce with the retort, `Aha, but what is art?'

Far better to accept that this kind of arrangement of real objects is art of a kind. Think of it as a tableau, or real life still-life, if you find this point troubling. Then you can go on to ask whether a particular example of this genre — given that it is art — is good, beautiful, effective or spiritually sustaining art. These are the interesting questions.

Whether one loves Hirst or loathes him, I think it has to be acknowledged that what he is doing is different from what art used to be. It is a mutation. On the video which rolls unceasingly at the entrance to the exhibition — and is essential viewing for anyone who wants to make sense of what goes on within — he says as much: 'Art should be like going to the cinema. It has a lot of impact, and it's visual, and you get a message.'

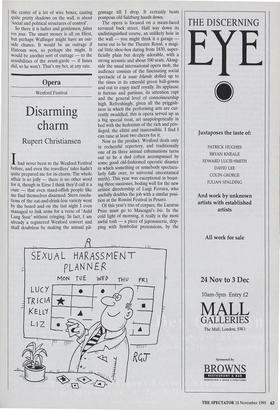

Now, that is actually not what art used to be about. It represents a definite reorienta- tion in the direction of brashness, sound- bite glibness, and superficiality. This may Damien Hirst's 'Mother and Child, Divided', 1993 be what is destined to happen to art in the age of the ad-man and information super- highway. But it's not all that's going on these days, even in the Turner Prize. Cal- lum Innes, the Scottish abstract painter, is still hanging on to the old view of art, if only by his fingertips.

Admittedly, many people might find his extremely pared-down, minimally austere paintings just as but-is-it-art-ish as Hirst's. One consists of a field of saturated red, with a dot of unstained canvas in the cen- tre; another consists of an expanse of white, stained and pock-marked as if left out in slightly dirty rain. But he talks about the effect of atmospheric light on his work, about beauty, about finding the right sort of tension in the image — old-fashioned, visual considerations. And, for all it's about not doing very much with not very much, subtly, when it works Innes's painting is rather beautiful. Hirst's paintings, on the other hand — which consist either of polka dots or swirls produced by dripping paint on a revolving disc — are all about present- ing utterly meaningless and emotional neu- trality with pzazz: nihilism with attitude.

Mark Wallinger is a rather engaging fig- ure — or at least he is in this careful selec- tion of his work. His exhibition at the Serpentine last spring was far scrappier and more tiresome. This collection leads off with his paintings connected with horse racing, the most likable of his work by far. These are pictures with a point — the `Half-Brothers' series, for example, consists of the front and back halves of two differ- ent horses from the same blood line, joined together (cutting animals into segments is a leitmotiv of this year's Turner).

This raises, according to the artist, ques- tions concerning the class system, heredi- tary principle and so forth. Selective breeding of the kind applied to race horses would have 'sinister connotations' if applied to human beings, he suggests. But since no one is currently breeding people to run faster, or for any other purpose, this worry seems a trifle unurgent. On the other hand, despite their carefully 'ironic' glossy finish, there is something about the paint- ings — perhaps because as well as having a Marxist-critical 'position' Wallinger also loves racing.

With Mona Hatoum, on the other hand, you just get the message, no love. 'Corps Etranger' is her most striking exhibit strikingly nasty, that is — comprising views of the interior of the artist's alimentary canal (both ends) with associated orifices. It differs only from the similar sort of footage often shown in medical pro- grammes on television by being vastly mag- nified, projected up through the floor and accompanied by very loud globberty-glob- berty noises. Apparently, it is about the vulnerability of the body and also the fears it arouses — being re-engulfed by the womb, for example. So that's the message, you needn't upset yourself by looking at it. Another work made up of a light bulb in the centre of a lot of wire boxes, casting quite pretty shadows on the wall, is about `social and political structures of control'.

So there it is ladies and gentlemen, fakes vos jewc. The smart money is all on Hirst, but perhaps Wallinger might have an out- side chance. It would be an outrage if Hatoum won, so perhaps she might. It would be another sort of outrage — to the sensibilities of the avant-garde — if Innes did, so he won't. That's my bet, at any rate.

Previous page

Previous page