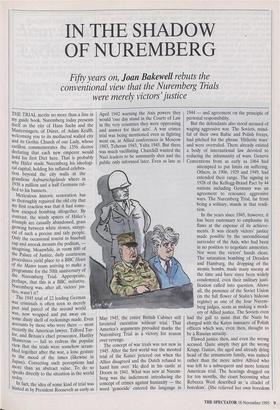

IN THE SHADOW OF NUREMBERG

Fifty years on, Joan Bakewell rebuts the

conventional view that the Nuremberg Trials were merely victors' justice

THE TRIAL merits no more than a line in my guide book. Nuremberg today presents itself as the city of Hans Sachs and the Mastersingers, of Darer, of Adam Krafft, welcoming you to its mediaeval walled city and its Gothic Church of our Lady, whose carillon commemorates the 1356 decree declaring that each new emperor would hold his first Diet here. That is probably why Hitler made Nuremberg his ideologi- cal capital; holding his inflated celebra- tion beyond the city walls at the grandiose Aufmarschgelande where in 1938 a million and a half Germans ral- lied to his banners.

Meticulous historic restoration has so thoroughly repaired the old city that mY first reaction was that it had some- how escaped bombing altogether. By contrast, the windy spaces of Hitler's triumph are casually abandoned, grass growing between white stones, untypi- cal of such a precise and tidy people. Only the occasional tourist in baseball cap and anorak mounts the podium, — imagining. Meanwhile, in room 600 of the Palace of Justice, daily courtroom procedures yield place to a BBC Heart of the Matter team arriving to make a programme for the 50th anniversary of the Nuremberg Trial. Appropriate, perhaps, that this is a BBC initiative. Nuremberg was, after all, victors' jus- tice, wasn't it?

The 1945 trial of 22 leading German war criminals is often seen as merely part and parcel of the second world war, now wrapped and put away on some dusty shelf of reckonings made. Even accounts by those who were there — most recently the American lawyer, Telford Tay- lor, and Britain's chief prosecutor, Hartley Shawcross — fail to redress the popular view that the trials were somehow scram- bled together after the war, a lone gesture to the mood of the times (likewise in Japan). Correcting such perceptions had more than an abstract value. To do so speaks directly to the situation in the world today.

In fact, the idea of some kind of trial was hinted at by President Roosevelt as early as April 1942 warning the Axis powers they would 'one day stand in the Courts of Law in the very countries they were oppressing and answer for their acts'. A war crimes trial was being mentioned even as fighting went on, at Allied conferences in Moscow 1943, Teheran 1943, Yalta 1945. But there was much vacillating. Churchill wanted the Nazi leaders to be summarily shot and the public only informed later. Even as late as May 1945, the entire British Cabinet still favoured execution without trial. That America's arguments prevailed marks the Nuremberg Trial as a victory for reason over revenge. The concept of war trials was not new in 1945. After the first world war the mooted trial of the Kaiser petered out when the Allies disagreed and the Dutch refused to hand him over. He died in his castle at Doom in 1941. What was new at Nurem- berg was the indictment introducing the concept of crimes against humanity — the word 'genocide' entered the language in 1944 — and agreement on the principle of personal responsibility.

In the years since 1945, however, it has been customary to emphasise its flaws at the expense of its achieve- ments. It was clearly victors' justice made possible by the unconditional surrender of the Axis, who had been in no position to negotiate amnesties. Nor were the victors' hands clean. The saturation bombing of Dresden and Hamburg, the dropping of the atomic bombs, made many uneasy at the time and have since been widely condemned, even their military justi- fication called into question. Above all, the presence of the Soviet Union (in the full flower of Stalin's hideous regime) as one of the four Nurem- berg judges, seem as making a mock- ery of Allied justice. The Soviets even had the gall to insist that the Nazis be charged with the Katyn massacre of Polish officers which was, even then, thought to be a Russian atrocity.

Flawed justice then, and even the wrong accused. Quite simply they got the wrong Krupp. Gustav, the aged and already dying head of the armaments family, was named rather than the more active Alfried who was left to a subsequent and more lenient American trial. The hearings dragged on for ten months, the court becoming what Rebecca West described as 'a citadel of boredom'. (She relieved her own boredom by having an affair with one of the Ameri- can judges.) In the end, twelve were sen- tenced to hang (one, Martin Bormann, in absentia), seven given prison sentences and three acquitted. The hangings numbered ten; Goering committed suicide in his cell.

Fifty years on, it is time to take the trial off history's shelf and re-evaluate the lega- • cy. Much can be found that was good: important indictments thrashed out between different legal systems; the princi- ple of individual responsibility written into international law; the importance of setting the historical facts straight. Two hundred thousand affidavits, 360 witnesses, 22 vol- umes, laid before the world the plan to exterminate the Jews. With typical thor- oughness the Germans had documented and filed the appalling evidence. This, then, was the record for historians, for humanity and more specifically for the Jews who had struggled to sustain a sense of moral order amid the horror, and now saw it acknowledged.

But what happened next surprises us today. Hartley Shawcross among others urged a list of some 500 further individuals to be tried. But Britain was tired of the war and its legacy. The public was bored. Par- liament voted without a single dissenting voice that trials should cease by the end of 1947. Nor were there any more trials by the International Military Tribunal. Many thousands who had committed odious crimes went unpunished. But history can- not close doors on the past that neatly. When justice is not satisfied, recriminations and pursuit continue. The work of Simon Wiesenthal, the kidnap and trial of Eich- mann, and in 1990 the passing by a British government of a War Crimes Act to revive prosecutions of a few now-aging war crimi- nals testify to the knowledge that unless some form of public resolution and concili- ation is reached the pain and outrage go on. It is a lesson for South Africa, for Rwanda and for Bosnia.

In 1993, for the fiist time since Nurem- berg, an International War Crimes Tri- bunal was set up to try charges of war crimes in former Yugoslavia. The United Nations has also authorised prosecutions of the genocide in Rwanda. These are ad hoc proceedings. But why only now? There have been plenty of wars and atrocities since 1945 that have prompted no such response, Vietnam, Cambodia and East Timor among them. The truth is that his- toric circumstances rarely converge to make such moves possible. Now they do. Now there is international outrage that ethnic cleansing is being openly promoted in former Yugoslavia. That it is happening in Europe, which long thought such things could never happen again, adds to the dis- gust. The world's media have thrust atroci- `Now dear, it's just that when you described her as a living doll, we assumed she was life-sized.' ties into every home and many consciences. Finally, and most significantly, the fall of the Berlin Wall and communism has meant that the UN Security Council can begin to act unanimously without the veto that stalled previous attempts. The times are ripe to bring the concepts of international law estab- lished at Nuremberg into play again.

There are many stumbling blocks, of course. Today's wars rarely end in the out- right victory of one side over the other, let alone of the good over the bad. Perpetra- tors of war crimes are needed at peace talks, when they can attempt to make amnesties for themselves the price of end- ing the slaughter. The Bosnian Serb leaders Karadzic and Mladic are two such. But the court at the Hague has brought indictments in absentia, and can now draw up and pub- lish the evidence. One day such leaders may be pariahs even in their own land.

South Africa also has currently to deal with its past and has chosen a different route. Its Commission for Truth and Rec- onciliation is offering the prospect of amnesty to many of those who come for- ward and confess the wrongs they did. But already Steve Biko's widow and various vic- tims groups are pressing for trials. In coun- tries where such commissions have been adopted — Chile and Argentina — discon- tent continues to rumble and former offenders still occupy positions of power.

What is needed is a permanent Interna- tional Criminal Court of Justice. This could apply an objectivity to proceedings. It could decide whether there should be a statutory limit on war crimes prosecutions, and how far down the line of command to bring charges. There have been many calls over the years for such a court. It is even now being drafted by the International Law Commission. It is pending before the Gen- eral Assembly. No time could be more pro- pitious. If not now, when?

Joan Bakewell will chair a BBC 1 Heart of the Matter Special from Nuremberg on 19 November at 10.50 p.m.

armany calling ... armany calling ...

Previous page

Previous page