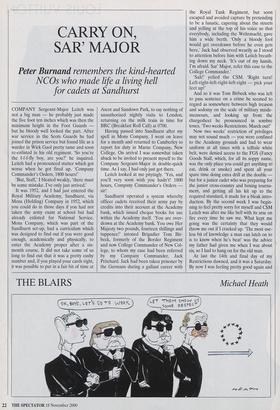

CARRY ON, SAR' MAJOR

Peter Burnand remembers the kind-hearted

NCOs who made life a living hell for cadets at Sandhurst

COMPANY Sergeant-Major Leitch was not a big man — he probably just made the five foot ten inches which was then the minimum height in the Foot Guards but he bloody well looked the part. After war service in the Scots Guards he had joined the prison service but found life as a warder in Wick Gaol pretty tame and soon re-enlisted in his old regiment. 'So you're the f-f-f-fly boy, are you?' he inquired. Leitch had a pronounced stutter which got worse when he got fired up. 'Company Commander's Orders, 1800 hours!'

`But, Staff,' I bleated weakly, 'there must be some mistake. I've only just arrived.'

It was 1952, and I had just entered the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, via Mons (Holding) Company in 1952, which you could do in those days if you had not taken the army exam at school but had already enlisted for National Service. Mons Company, which was part of the Sandhurst set-up, had a curriculum which was designed to find out if you were good enough, academically and physically, to enter the Academy proper after a six- month course. It did not take some of us long to find out that it was a pretty cushy number and, if you played your cards right, it was possible to put in a fair hit of time at Ascot and Sandown Park, to say nothing of unauthorised nightly visits to London, returning on the milk train in time for BRC (Breakfast Roll Call) at 0700.

Having passed into Sandhurst after my spell in Mons Company, I went on leave for a month and returned to Camberley to report for duty in Marne Company, New College. On arrival I was somewhat taken aback to be invited to present myself to the Company Sergeant-Major in double-quick time. As I say, I had only just got there.

Leitch looked at me pityingly. 'Yes, and you'll very soon wish you hadn't! 1800 hours, Company Commander's Orders sir!

Sandhurst operated a system whereby officer cadets received their army pay by credits into their account at the Academy bank, which issued cheque books for use within the Academy itself. 'You are over- drawn at the Academy bank. You owe Her Majesty two pounds, fourteen shillings and tuppence!' intoned Brigadier Tom Bir- beck, formerly of the Border Regiment and now College Commander of New Col- lege, to whom my case had been referred by my Company Commander, Jack Pritchard. Jack had been taken prisoner by the Germans during a gallant career with the Royal Tank Regiment, but soon escaped and avoided capture by pretending to be a lunatic, capering about the streets and yelling at the top of his voice so that everybody, including the Wehrmacht, gave him a wide berth. 'Only a bloody fool would get overdrawn before he even gets here,' Jack had observed wearily as I stood to attention before him with Leitch breath- ing down my neck. 'It's out of my hands, I'm afraid. Sar' Major, refer this case to the College Commander.'

'Sall!' yelled the CSM. 'Right turn! Left-right-left-right-left-right — pick your feet up!'

And so it was Tom Birbeck who was left to pass sentence on a crime he seemed to regard as somewhere between high treason and sodomy on the scale of military misde- meanours, and looking up from the chargesheet he pronounced in sombre tones, 'Two weeks Restrictions. March out!'

Now two weeks' restriction of privileges may not sound much — you were confined to the Academy grounds and had to wear uniform at all times with a telltale white belt, were denied access to the FGS (Fancy Goods Stall, which, for all its soppy name, was the only place you could get anything to eat, drink or smoke) and spent all your spare time doing extra drill at the double but for a junior cadet who was preparing for the junior cross-country and boxing tourna- ment, and getting all his kit up to the required standard, it made for a bleak intro- duction. By the second week I was begin- ning to feel pretty sorry for myself and CSM Leitch was after me like hell with its arse on fire every time he saw me. What kept me going was the certainty that they would throw me out if I cracked up. 'The most use- less bit of knowledge a man can latch on to is to know when he's beat' was the advice my father had given me when I was about six, so I had to hang on for the old man.

At last the 14th and final day of my Restrictions dawned, and it was a Saturday. By now I was feeling pretty good again and had worked out that if I could get away in time from my extra drill, I could get to Tweseledown for the last four races. My Restrictions ended officially at midnight, but what the hell!

The drill staff at Sandhurst were decent men and I had already discovered that Sergeant Murphy, Irish Guards, who was in charge of extra drill that day, was a thor- oughly good egg. Sure enough, he let me go a few minutes early and I was leaning over the rails of the paddock at Twesele- down 40 minutes later.

At BRC on Monday morning CSM Leitch called us to attention and then shouted my name.

`Staff!' I yelled back.

`My office straight after this!'

The wheel had come off again, and this time it was serious. An unspeakable brute, a senior cadet in Marne Company, had spotted me at Tweseledown and blown the whistle on me. Needless to say, he sank immediately into total military obscurity after Sandhurst, but he did for me that day. Tom Birbeck had a major sense of humour failure, Leitch went ballistic and I got another 28 days' Restrictions, during which I was knocked out cold in the junior boxing by a right hook I never even saw, thrown by a paragon of military virtue who, as well as having a mean right hand, went on to become a four-star general.

Leitch had me on the run and he knew it. If there was one thing he could not stand, it was what he considered a `f-f-f-fly boy', and he had me down as just that. To say he made my life unbearable over the next month would be over the top, but he did his best. It was character-building stuff.

Halfway through the extra dose of Restrictions I was making my way back from extra drill and feeling pretty low when I turned a corner and found myself face to Flippin' heck; Dad. There's no need to cross- examine me just because I come in half an hour late.' Eh-oh.'

face with the imposing figure of Academy Sergeant-Major J.C. Lord, Grenadier Guards. 'Good afternoon, Mr Burnand, sir!' he said with a broad smile which clear- ly meant, 'I know all about the trouble you're in but I'm counting on you to come through it!' Jack Lord was a man among men and a soldier through and through.

To suggest he swore at people or insult- ed them (Letters, 27 May) is about as far from the truth as you can get, as the for- mer members of the staff of the RMA Sandhurst pointed out in their letter of 16 September. Lord had great style and a sense of humour, which meant you ended up on his side even when you found your- self on a charge.

Towards the end of my senior term I decided to cultivate my hair to a length becoming a cavalry officer but had not progressed very far before the next Acade- my parade, over which Jack Lord presided. As he swept majestically past Manic Com- pany, giving us the once-over, he stopped and turned to face us. 'Take off your cap, that gentleman in the Third Reich!' Tucked away in the comparative safety of the rear rank, I knew who he was after; a lot of time had been spent on reshaping my cap so that it looked like the type favoured by Rommel's Afrika Korps. 'Yes, you, sir, Mr Burnand, sir!' Off came the cap and down fell the hair. 'Idle haircut, Sar' Major.' Sahr yelled Leitch. I was in the book but I still felt good.

A few days before I was due to pass out I caught the milk train back from London, only to find there were no taxis at Camber- ley station. This had the makings of a dis- aster as I had to walk back and was bound to miss BRC. On a short cut through the woods Leitch overtook me on his bicycle, but never turned his head or said a word then or later.

From that year onwards, wherever I was in the world, a Christmas card somehow arrived with the simple message: 'To Mr Bumand from Murdo Leitch.' That was all he said and all he needed to say. The cards kept coming until he died.

Previous page

Previous page