THE AMERICAN RECESSION By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

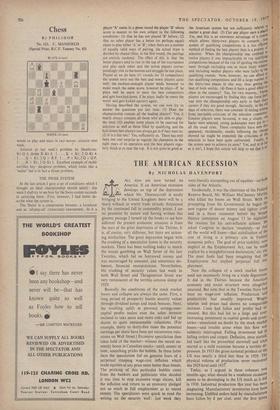

is, of course, very different, but there are sicken- ing similarities. The great depression began with the crashing of a speculative boom in the security markets. There has been nothing today to match the insane gambling on Wall Street of the late Twenties, which fed on borrowed money and was encouraged by unsound, and sometimes dis- honest, financial manipulations. Nevertheless, the crashing of security values last week in both Wall Street and Throgmorton Street was very reminiscent of the terrible autumn slump of 1929.

Basically the conditions of the stock market boom and collapse are always the same. First, a long period of prosperity boosts security values through dividend jumps and stock bonuses. Next, the resulting uplift in personal savings-cum- capital profits makes even the sober investor inclined to take more and more risks and bid up shares to quite unreasonable valuations. (For example, thirty to thirty-five times the potential earnings per share have been not uncommon valu- ations on Wall Street.) Excessive speculation then takes hold of the market—witness the recent un- seemly boom in Canadian stocks—until, sooner or later, something pricks the bubble. In these latter days the speculation fed on genuine fears of a perpetual creeping wage-cost inflation which made equities at any price seem better than bonds. The pricking of this particular bubble came from the bankers and politicians who decided it was time to stop excessive wage claims, kill the inflation and return to an economy pledged not so much to full employment as to sound money. The speculators were quick to read the writing on the security wall : last week they were literally stampeding out of equities—on both sides of the Atlantic.

Incidentally, it was the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Mr. William McChesney Martin, who killed the boom on Wall Street. With n° prompting from the Government he began the new regime of dearer money and tighter credit and in a blunt statement before the Senn°, finance committee on August 13 he explain the reasons for his anti-inflation actions. He asked Congress to declare 'resolutely—so that all the world will know—that stabilisation of the cost of living is a primary aim in Federal economic policy. The goal of price stability, novi implicit in the Employment Act, can be made explicit by a straightforward declaration,' etc. etc' The poor fools had been imagining that the Employment Act implied perpetual full env ployment. Now the collapse of a stock market boom need not necessarily bring on a -trade depression. It did in the Thirties because the American economy and social structure were altogether unsound. But note that in the Twenties there had, been no wage-cost inflation. Production and productivity had steadily improved. Wages, salaries and prices had shown no comparable increase. Costs had fallen and profits had in- creased. But this had led to a large and ever' increasing investment in capital goods and inven' tories—stimulated no doubt by the stock market boom—and trouble arose when this flow so5 suddenly interrupted. Falling investment led 10 falling orders and output. Deflation, once started, fed itself like the proverbial snowball and what started as a mild recession became a terrible de' pression. In 1933 the gross national product of the US was nearly a third less than in 1929. The physical volume of production never recovered the 1929 level until 193/..

Today, as I argued in these columns two months ago, what should be a moderate recession seems to be developing in the US much as it did in 1930. Industrial production tbis year has been stagnating. Manufacturers' inventories have been increasing. Unfilled orders held by manufacture" have fallen by 8 per cent, over the first seven

months; new orders received in June and July were the lowest for the past two years. Capital spending on new plant and equipment is 'topping

• off': estimated expenditures for the fourth quarter are lower and deeper cuts are anticipated for 1958. Defence spending is being reduced from $42,400 million to $38,000 million a year in the fiscal year ending next June. The oil industry is , suffering from a temporary over-production: the automobile trade is facing the annual gamble of model changes on which it has staked a huge in- vestment. It is obviously a very critical time. Consumer spending is still increasing, but, as in

• the Thirties, this will not be enough to offset a serious decline in investment spending if that develops.

And it surely will develop if the confidence

of the businessman is not quickly restored-by increased government spending (on missiles?) or by cheaper money. At the moment it has been upset by the rise in wages ahead of productivity, by the fall in profit margins and by the determina- tion of Mr. William McChesney Martin to pro- duce sound money, which means, in effect, producing sufficient unemployment to break the wage-cost inflation. What businessman would not cut his projected capital programme on such a prospect?

Yet the American business prospect, uncertain and critical though it is, is surely brighter than the British. Here the Government has gone out of its way to shatter business confidence with a Bank rate shock. It will be many moons-and satellites -before it is restored.

Previous page

Previous page