Architecture

The Golden City: The Architecture and Imagination of Beresford Pite (1861-1934) (RIBA Heinz Gallery, till 23 October)

Architect with a mission

Alan Powers

The wind, the wind, the wind blows high The snow is falling from the sky, Maisie Drummond says she'll die For want of the Golden City.

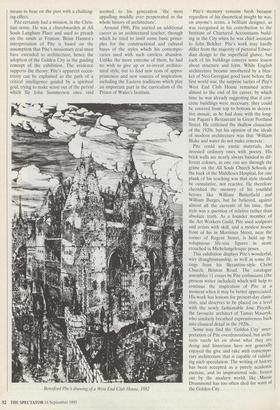

This children's rhyme provided the title for Sacheverell Sitwell's final prose book in 1973, a testimony of stoic resistance to the modern world. Beresford Pite, as a young, combative, visionary architect, used the motto 'El Dorado Yo Trovado' CI have found the Golden City') for the entry he submitted for the annual Soane Medallion competition in 1882. The subject was a West End Club House, but Pite produced no routine Barryesque palazzo. Instead, his vision of the Golden City at this date con- sisted of crumbling Gothic turrets, with London redesigned in the manner of Nuremburg to match.

This drawing, given its widest currency as an illustration in Sir John Betjeman's First and Last Loves, has often appeared an inexplicable piece of eccentricity. Pite's buildings, over a long career, are all indi- vidually remarkable, down to the lower arch on the Piccadilly entrance to the Burlington Arcade, completed in 1931, with its great scrolls and tiny sculpture.

During the revival of interest in Edwar- dian architecture in the 1970s, Pite was established as one of the heroes, with his fluid treatment of classicism in the insur- ance offices at the corner of Euston Square and his meticulous but down-to-earth buildings in the poorer parts of Maryle- bone. The exhibition at the Heinz Gallery (21 Portman Square, W1) offers an addi- tional layer of interpretation. It is curated by Brian Hanson, director of studies at the Prince of Wales's Institute of Architecture, who brings the Institute's active concern with the regeneration of building and architecture through practical and spiritual means to bear on the past with a challeng- ing effect.

Pite certainly had a mission, in the Chris- tian sense. He was a churchwarden at All Souls Langham Place and used to preach on the sands at Frinton. Brian Hanson's interpretation of Pite is based on the assumption that Pite's missionary zeal must have extended to architecture, hence the adoption of the Golden City as the guiding concept of the exhibition. The evidence supports the theory: Pite's apparent eccen- tricity can be explained as the path of a critical intelligence guided by a spiritual goal, trying to make sense out of the period which Sir John Summerson once said seemed to his generation `the most appalling muddle ever perpetrated in the whole history of architecture'.

Around 1900, Pite started an additional career as an architectural teacher, through which he tried to instil some basic princi- ples for the constructional and cultural bases of the styles which his contempo- raries used with such careless abandon. Unlike the more extreme of them, he had no wish to give up or re-invent architec- tural style, but to find new tests of appro- priateness and new sources of inspiration, including the Eastern traditions which play an important part in the curriculum of the Prince of Wales's Institute.

Beresford Pite's drawing of a West End Club House, 1882

Pite's memory remains fresh because regardless of his theoretical insight he was, on anyone's terms, a brilliant designer, as was recognised in his contribution to the Institute of Chartered Accountants build- ing in the City when he was chief assistant to John Belcher. Pite's work may hardly differ from the majority of pictorial Edwar- dian design to the superficial glance, but each of his buildings conveys some lesson about structure and form. While English architecture became smothered by a blan- ket of Neo-Georgian good taste before the first world war, the surprise tactics of Pite's West End Club House remained active almost to the end of his career, by which time he was already suggesting that if con- crete buildings were necessary, they could be covered from top to bottom in decora- tive mosaic, as he had done with the long- lost Pagani's Restaurant in Great Portland Street. He criticised the shallow classicism of the 1920s, but his opinion of the ideals of modern architecture was that 'William Blake and water do not make concrete'.

Pite could use exotic materials, but invested ordinary ones with poetry. His brick walls are nearly always banded in dif- ferent colours, as one can see through the grime on the All Souls Church Schools at the back of the Middlesex Hospital, for one plank of his teaching was that style should be cumulative, not reactive. He therefore cherished the memory of his youthful heroes like William Butterfield and William Burges, but he believed, against almost all the currents of his time, that style was a question of relative rather than absolute truth. As a founder member of the Art Workers Guild, Pite used sculptors and artists with skill, and a modest house front of his in Mortimer Street, near the corner of Regent Street, is held up by voluptuous life-size figures in stone crouched in Michelangelesque poses.

This exhibition displays Pite's wonderful, wiry draughtsmanship, as well as some fit- tings from his Byzantine-style Christ Church, Brixton Road. The catalogue assembles 11 essays by Pite enthusiasts (the present writer included) which will help to continue the inspiration of Pite at a moment when it may be better appreciated. His work has lessons for present-day classi- cists, and deserves to be placed on a level with the newly fashionable Jose Plecnik, the favourite architect of Tamas Masaryk, who similarly breathed expressiveness back into classical detail in the 1920s.

Some may find the 'Golden City' inter- pretation of Pite overdratnatised, but archi- tects rarely let on about what they are doing and historians have not generally enjoyed the give and take with contempo- rary architecture that is capable of validat- ing such speculation. The writing of history has been accepted as a purely academic exercise, and its inspirational side, frozen out by the modern world, like Maisie Drummond has too often died for want of the Golden City.

Previous page

Previous page