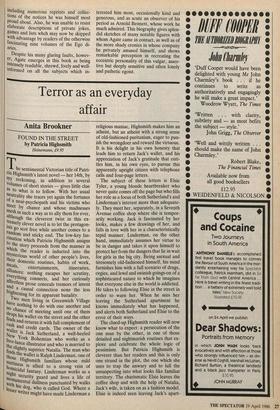

Terror as an everyday affair

Anita Brookner

FOUND IN THE STREET

by Patricia Highsmith Heinemann, f9.95

The sentimental Victorian title of Patri- cia Highsmith's latest novel — her 14th, by MY reckoning, in addition to several volumes of short stories — gives little clue as to what is to follow. With her usual neutrality she traces yet again the fortunes of a near-psychopath and his victims who meet by chance and whose madnesses mesh in such a way as to ally them for ever, although the cleverest twist in this ex- tremely clever novel is to let the protagon- ists go scot free while another comes to a random and sticky end. The low-key fas- cination which Patricia Highsmith assigns to the story proceeds from the manner in Which the reader is inducted into the mysterious world of other people's lives, their domestic routines, habits of work, meals, entertainments, itineraries, alliances: nothing escapes her scrutiny, everything connects, and her curiously affectless prose conceals tremors of intent and a causal connection none the less frightening for its apparent banality. Two men living in Greenwich Village have nothing to do with one another and no chance of meeting until one of them drops his wallet on the street and the other finds and returns it with full complement of cash and credit cards. The owner of the Wallet is Jack Sutherland, a well-heeled New York Bohemian who works as a free-lance illustrator and who is married to the slightly superior Natalia. The man who Inds the wallet is Ralph Linderman, one of those Highsmith familiars whose mild .nuttiness is allied to a strong vein of homicidal fantasy. Linderman works as a night security guard and lives a life of monumental dullness punctuated by walks with ith his dog, who is called God. Where a lesser writer might have made Linderman a religious maniac, Highsmith makes him an atheist, but an atheist with a strong sense of old-fashioned puritanism, eager to pun- ish the wrongdoer and reward the virtuous.

It is his delight in his own honesty that leads him to return Jack's wallet, and his appreciation of Jack's gratitude that enti- tles him, in his own eyes, to pursue this apparently upright citizen with telephone calls and four-page letters. The subject of these letters is Elsie Tyler, a young blonde heartbreaker who never quite comes off the page but who fills her role as a focus of both Sutherland's and Linderman's interest more than adequate- ly. They meet her, separately, in a Seventh Avenue coffee shop where she is tempor- arily working. Jack is fascinated by her looks, makes a few drawings of her, and falls in love with her in a characteristically tepid manner. Linderman, on the other hand, immediately assumes her virtue to be in danger and takes it upon himself to protect her from the dangers that lie in wait for girls in the big city. Being asexual and tiresomely old-fashioned himself, his mind furnishes him with a full scenario of drugs, orgies, and lewd and swinish goings-on of a sophisticated nature to which he imagines that everyone else in the world is addicted. He takes to following Elsie in the street in order to warn her. When he sees her leaving the Sutherland apartment he knows immediately what has happened, and alerts both Sutherland and Elsie to the error of their ways. The clued-up Highsmith reader will now know what to expect: a persecution of the one man by the other, in one of those detailed and nightmarish routines that ex- plore and celebrate the whole logic of pessimism. But Patricia Highsmith is cleverer than her readers and this is only one strand in the plot, the one which she uses to trap the unwary and to lull the unsuspecting into what looks like familiar territory. The charismatic Elsie leaves the coffee shop and with the help of Natalia, Jack's wife, is taken on as a fashion model. Elsie is indeed seen leaving Jack's apart- ment but as Elsie is gay she is in little danger. Elsie is in fact a mildly unpleasant character, despite Patricia Highsmith's evi- dent indulgence towards her, but perhaps she is no more unpleasant than Linderman. Her blamelessness, like that of Sutherland himself, is mainly a negative affair and consists of not doing a great deal of harm to others. All the characters are flawed, and perhaps Linderman alone represents a lesser degree of venality. But Linderman is a nuisance and a bore. In the country of the laid-back he is an intruder.

Elsie, as Natalia's protegee, is intro- duced to the Sutherlands' circle of friends and attends various parties in their com- pany. These tend to limp on into the small hours and on one occasion Linderman, walking his dog, sees Elsie and her friend Marion leaving the Sutherland apartment at 6 a.m. He knows what to conclude from this, of course, and redoubles his efforts to intercept and, if possible, to interrogate either Elsie or Jack or preferably both. His grand design is to bring Elsie and Jack together and accuse them in the presence of Jack's wife. What he does not know is that Elsie is not Jack's lover but Natalia's: him imagination will not stretch that far. Nor will he ever understand what is hap- pening because his world view is too febrile to allow for the slyer and more subtle connections that these bored and healthy people make with each other.

The Sutherlands' circle now consists of Jack and his wife, Elsie, and Elsie's friend, Marion. These people tend to telephone to warn each other of Linderman's most recent approach. Just when this second routine is becoming familiar, a murder is committed.

The peculiar spell which Patricia High- smith lays on the reader is one of apparent inevitability. There seems to be no escape from the remorseless logic of what has been set up. In this she is effortlessly superior to other writers of suspense stor- ies because she does not furnish her char- acters with anything but the most thread- bare of personalities: their interaction is like the ticking of a clock. The author does not seem to intervene at any point to establish authorship, and the bare colour- less prose and the circumstantial detail contribute to a narrative style so curiously insistent as to instil feelings of genuine uneasiness. There is no one quite like her, although her morbidity may raise the ghosts of some of Simenon's finest novels, like Tante Jeanne or Le Temps d'Anais. She presents terror as something impassive, unnoticeable, almost, an everyday affair.

Her great gift, apart from the mastery of her plotting, is to make one curious about other lives, to restore to them their dimen- sion of strangeness, too often eroded in fiction by the easy process of identification. It is to be hoped that not too many people identify with Patricia Highsmith's charac- ters: if they do they are in more danger than they know, and so are the rest of us.

Previous page

Previous page