Political Commentary

Police and pickets whose violence?

Hugh Macpherson

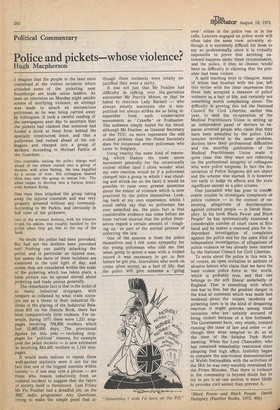

I imagine that t'ne people in the land most concerned at the violent incidents which attended some of the picketing near Scunthorpe are trade union leaders. As seen on television on Monday night amidst scenes of terrifying violence, an attempt was made to attack an unconscious policeman as he was being carried away by colleagues. It took a careful reading of the newspapers next day to ascertain that the pickets had claimed that someone had hurled a brick at them from behind the specially constructed fence, and that a policeman had rushed ahead of his colleagues and charged into a group of dockers. According to Michael Parkin of the Guardian. . . .

One constable leading the polic charge well ahead of the others rushed into a group of dockers with arms flailing. He was engulfed by a scrum of men. His colleagues heaved their way into the group to rescue him. The affair began to develop into a furious brawl, with helmets flying.

One man then attacked the group taking away the injured constable and was very properly arrested without any ceremony. According to Mr Parkin, and obviously in full view of the picketers,

One of the arrested dockers, with his trous3rs round his ankles, was roughly handled by the police when they got him to the top of the bank.

No doubt the police had been provoked. But had not the dockers been provoked too? Nothing can justify attacking the police, and in particular an injured man, but unless the facts of these incidents are examined in the cold light of day, and unless they are considered within the scale of the picketing which has taken place, a false picture can be spread abroad about picketing and trade unions generally.

' The remarkable fact is that in the midst of so many industrial stoppages, with tempers so inflamed by what trade unionists see as a threat to their industrial liberties in the placing of the Industrial Relations Bill on the Statute Book, there has been comparatively little violence. For example, during 1971 there were 1,221 stoppages involving 704,800 workers which' lost 10,965,000 days. The provisional figures for this year — excluding stoppages for ' political' reasons, for example over the jailed dockers — is now estimated as involving 883,400 workers in 1,194 stoppages.

It would seem tedious to repeat these well-quoted statistics were it not for the fact that one of the biggest enemies within society — if one may coin a phrase — are those who reason inductively from an isolated incident to suggest that the fabric of society itself is threatened. Last Friday Mr Vic Feather had a dreadful job, on the BBC radio programme Any Questions, trying to make the simple point that al

though these incidents were totally unjustified they were a rarity.

It was not just that Mr Feather had difficulty in talking over the garrulous astonomer Mr Patrick Moore, or that he failed to convince Lady Barnett — who always stoutly maintains she is nonpolitical but always strikes me as being inseparable from such conservative monuments as ' Crawfie ' or Foxhunter. The audience simply bayed for his blood, although Mr Feather, as General Secretary of the TUC, no more represents the odd violent picketer than the Home Secretary does the occasional errant policeman who turns to burglary.

Using exactly the same kind of reasoning. which blames the trade union movement generally for the occasionally violent striker (and I often wonder what my own reaction would be if a policeman charged into a group in which I was standing and struck me on the face) it would be possible to raise even greater questions about the extent of violence which is now practised by the police themselves. Looking back at my own experience, whilst I could safely say that no policeman has ever assaulted me, the plain fact is that considerable evidence has come before me from various sources that the police themselves regard a certain amount of 'roughing up' as part of the normal process of enforcing the law.

One of the sources is from the police themselves and I felt some sympathy for the young policeman who told me that when going to arrest a man with a violent record it was necessary to get in first before he got you. Journalists who work on crime often accept, as a fact of life, that the police will give someone a 'going over' either in the police van or in the cells. Lawyers engaged on police work will often take the same view privately although it is extremely difficult for them to say so professionally since it is virtually impossible to prove that anything untoward happens under these circumstances, and the police, if they so choose, would have no difficulty in claiming that the prisoner had been violent.

A spell teaching boys in Glasgow, many of whom had brushes with the law, left this writer with the clear impression that these lads accepted a measure of police' violence as a fact of life, and certainly not something worth complaining about. The difficulty in proving this led the National Council for Civil Liberties, earlier this year, to seek the co-operation of the Medical Practitioners Union in setting up an independent panel of doctors to examine arrested people who claim that they have been assaulted by the police. Like lawyers involved in the same problem, doctors have their professional difficulties and the monthly publication of the Medical Practitioners Union made it quite clear that they were not reflecting on the professional integrity of colleagues who were police surgeons. In fact the Association of Police Surgeons did not object and the scheme was started. It is however too early to judge its effects and the scale significant except as a pilot seneme.

One journalist who has gone to constderable trouble to investigate complaints of police violence — in the context of examining allegations of discrimination against coloured people — is Derek Humphry. In his book Black Power and Black People* he has systematically examined a considerable number of court cases at first hand and he makes a reasoned plea for independent investigation of complaints against the police and for the same kind of independent investigation of allegations of police violence as has already been started by the National Council for Civil Liberties.

To write about the police in this vein is, of course, an open invitation to authors of abusive letters who claim that we have the least violent police force in the world, which is probably true, and that one belongs to the soft liberal underbelly of England. That is something with which one has to live, but the greatest danger in the kind of comment which was made last weekend about the violent incidents at picketing lines is in the kind of despairing reaction it might provoke among trade unionists who are unfairly accused of being violent because of a few hotheads. The Government have, very wisely, resisted running the issue of law and order — although they were tempted to do so at the time of the Selsdon Park Hotel meeting. When the Lord Chancellor, who has remained remarkably restrained since adopting that high office, foolishly began to compare the non-violent demonstrations of Welsh Nationalists with the activities of

the IRA he was very sensibly restrained by the Prime Minister. That there is violence

in the community is beyond doubt but to try to pin it on one section is more likely to provoke civil unrest than prevent it.

Black Power and Black People Derek Humphry (Panther Books, 1972: 40p)

Previous page

Previous page