LIVING FROM HAND TO MOUTH

A new pattern of food distribution is dividing Britain

concern about the accessibility of good food

EVERY SO often in the history of British food, well-heeled public figures advise Poorer people how to cook and eat things that they themselves would rarely consider palatable. This recurring social quirk is symbolised by Nancy Astor and the cod.

This spring, in their consumer briefings, the

investment analysts Henderson Crosthwaite drew attention to the fragmentation' of the UK retailing food mar- ket during the Eighties. A two-tier food market seems to be developing in the UK in which a small number of big re- tailers are dashing up- market, scenting the spending power of mobile households with a fan of credit cards at their command. Meanwhile, people with- out cars and high creditworthiness are becoming a second tier with less access to affordable good food. Beneath them are the signs of an emergent third tier low-income people who cannot afford to buy sufficient food from any conventional retailer. These people increasingly rely for part of their personal or family food intake on the redistribution of `free food' by often reluctant voluntary bodies. To encourage full debate about the moral, practical and political questions posed by 'food welfare', the recently formed National Food Alliance published a report on 18 July entitled Food Provision for People with Low Incomes in the UK (available from the

National Council for Voluntary Organisa- tions, 26 Bedford Square, London WC1). One factor in the current maldistribution of food in Britain is the gradual removal of credit from lower-income people. Until the early Seventies, people of all classes could get credit for food. At the upper end of the social scale housewives could (and still do) run accounts with butchers and other traditional suppliers, while poorer people had 'tick' at small grocers' shops based on local goodwill and regular personal con-

tact. The chance to get informal credit has been dramatically reduced (`the death of tick') as food retailing becomes dominated by a small number of impersonal giant firms. In February 1986 The Grocer claimed that 20 per cent of expenditure on groceries in Britain is now made by cheque and a further six per cent by credit card. As big retailers follow Marks & Spencer in encouraging more credit card use for food purchase, this percentage will rise.

For airy consumers used to check-out deference when buying three aubergines and a pineapple with a Barclaycard, `second-tier' food shopping is a world apart. Based at Prestatyn in north Wales, Kwik Save (Britain's most rapidly expand- ing food chain) has approximately 640 stores mainly in Wales and the North and is now expanding into the south-east. The Kwik Save PR man at Prestatyn denied that the raison d'être of the operation is `subsistence retailing' (`You should see the F-registered cars in the car parks') but these interesting shops appear to me to be catering for the new `second-tier' food consumers. Kwik Save supermarkets offer a very limited range of brand-name goods and seem to be aimed at low-income women who are afraid to shop in other super- markets in case they are `tempted' and wreck a family budget by blow- ing often a matter of pence more than they should.

Kwik Save offered goods I had never noticed before — packets of Birds' Whisk 'n' Serve Brandy Flavour Sauce at 41p (`Instructions. Put kettle on to boil . . .') and Bird's Eye Potato Ketchips (`Crispy spiky tubes of delicious mashed potato with a real tomato ketchup centre'). Two huge wooden pallets bore mountains of granulated sugar bags and, through a warehouse door, another sugar Everest was waiting in the wings. On the 'de- licatessen' and butchery counter, set out with stiff Dutch-garden rows of red and green plastic parsley, one could buy 5113 of stewing lamb for £2.99. 'That's a best- seller,' said an assistant pointing at 10Ib of chicken legs for £5. 'Mind you, we can't sell joints.' Something long and greyish called 'luncheon sausage' was marked with a sign saying 'not more than 20 per cent added water'. It occurred to me that in the last century people who watered milk were criminals, but today people who water meat are merely food tycoons. Further on I was just noting down the price of tiny pearl pink bars of Cusson's My Fair Lady soap (11p) which I had never before seen, when a supervisor in a red and white dress came up rather sharply. 'We don't like people walking round writing down prices in these shops.' But I'm a consumer. All house- wives compare prices.' As I was suspicious- ly directed towards the checkout a huge red and white placard said, THANKYOU FOR BEING A NO NONSENSE SHOP- PER. Sugars and animal fats were plentiful at Kwik Save but fresh fruit and vegetables were not on sale.

The price of food was recognised by both Rowntree and Beveridge when calcu- lating minimum welfare payments, but it has been ignored by the Fowler review of the Social Security Act. As benefits de- crease and the price of food rises in preparation for the completion of the European market in 1992, low-income families are increasingly forced to 'trade down' to worse and worse quality food in order to survive. 'Diseases of affluence' is a misleading term. The cancers, heart dis- ease and obesity caused by over- consumption of saturated fats, sugar and salt (and under-consumption of fibre) are, in fact, the diseases of the poor in affluent Western societies. Like the patrons of expensively simple Modernism in the Thir- ties, it is only the most affluent who can afford the new dietary consensus of organic bread, pasta, vegetables and fruit and hormone-free poultry and lean meat. It is probably true that if low-income adults confined themselves to two big plates of raw vegetables and a couple of slices of rough wholemeal bread a day they would be healthier, but this ignores the psycholo- gical importance of food so well defined by George Orwell in The Road to Wigan Pier:

The ordinary human being would sooner starve than live on brown bread and raw carrots, and the peculiar evil is this, that the less money you have, the less inclined you feel to spend it on wholesome food. A millionaire may enjoy breakfasting off orange juice and ryvita biscuits . . . [but] . . .

When you are underfed, harassed, bored and miserable, you want something a little bit 'tasty'.

As the food historian Christopher Driver remarked in The British at Table 1940-80 (Chatto, 1983) nutrition bears the same relation to pleasurable eating as births and deaths notices do to great literature.

Unlike absolute starvation, which has been eradicated in the First World, there is no universal definition of hunger. But new interest in nutrition during the Eighties has produced a medically accepted definition that a hungry child or adult is chronically short of the nutrients essential for growth and good health. In Scientific American in February 1987, J. Larry Brown, chairman of the Physician Task Force on Hunger in America (based at the Harvard School of Public Health) estimated from 20 recent national studies that as a result of federal cutbacks in welfare feeding programmes during the Eighties some 12 million Amer- ican children and eight million American adults are hungry (nine per cent of the population). For the past five years, volun- tary agencies like St Bartholomew's Epis- copalian Church in New York have tried to cope with a fraction of this unmet need by giving out weekly packages of free food.

Edinburgh is a city which seems quite unselfconsciously to have begun the wide- spread voluntary distribution of food, in this case through its tightly organised networks of Episcopalian and Roman Catholic churches. Brother Bernard is a young Jericho Benedictine, who with two others moved from the west coast of Scotland to Edinburgh seven months ago to 'try to meet needs as they arose'. The order is presently converting the old church of St Francis in Lothian Street into a hostel to accommodate unwanted people such as discharged psychiatric patients and chronic alcoholics. Meeting hunger in Edinburgh has also become part of their work ('we are approached by a lot of poor families three or four days before their giro appears'). Catholic churches in Edinburgh now hold 'Tin Sundays' on which people are encouraged to bring tins of food (preferably meat and fish), tea-bags and other basics. A local white-sliced Sunblest factory gives the order 30 loaves a week. On Sundays, the Jericho Benedictines try to cater for sometimes as many as 250 people, offering tea and sandwiches in the morning and a substantial cooked lunch. Episcopalian churches also hold tin appeals. When the Revd Geoffrey Connor, Vice-Provost of St Mary's Episcopalian Cathedral, first appealed for food on a church notice-board he received rather hamperish things like tins of game soup- 'But people really need basic things like corned beef, baked beans and spaghetti. If they're regular, I give them money for bread, tea-bags and sugar.'

Edinburgh also has a particularly digni- fied and enlightened example of what are called in Europe 'Restaurants of the Heart', These are restaurants pioneered by a popular comedian in France (they have spread to other north European countries) which offer very cheap but nutritious meals to low-income customers.

A few minutes' walk from the platform at Waverley Station where early-morning travellers emerge rather dazed from the Inter-City sleeper, lies The Old Sailor's Ark, an early 'Restaurant of the Heart' given outright to Old St Paul's Episcopa- lian Church last year. The Ark was opened in 1936 by the will of Captain Charles Taylor who bequeathed his entire fortune to found a restaurant for the 'destitute and deserving poor'. Originally, the five-storey building (in which the Captain, like Glas- gow's tea-room ladies, took a close design interest) also had a sea captain's restaurant on the top floor with waitress service. Coffee pots and other surviving crockery still bear 'The Ark' scripted in blue.

Three tall windows filled The Ark with the promise of a Scottish summer morning. On the stone-flagged floor were 20 or so small wooden tables topped with very clean oil-cloth. Beyond them, on the win- dow sills and on a corner piano, was a haze of bright pink Busy Lizzies and geraniums. Behind the serving counter, in a welcoming atmosphere of scrubbed Scottish decency, six volunteers worked steadily at a big Thirties' catering range, cooking breakfast orders as they came in. Over the counter hung a glazed wooden menu holder with a Gothic top, listing porridge, sausages, black pudding, bacon, eggs, hamburgers, milk and coffee (all at 10p each) and beans, toast, marmalade or jam and tea (all at 5p). The Ark is open from seven to 11.30 a.m. and specialises in big Scottish break- fasts. Marilyn Chatterly, who runs it, decided that it was best to 'do a bit of the day and do it well'. Jenner's department store on Princes Street gives her day-old bread and cakes, but she lamented that an Edinburgh branch of Safeways had just installed an expensive machine to shred unwanted loaves.

Marilyn Chatterly is a loving but shrewd woman who has no use for 'sugary charity'. She feels that hand-outs are 'a condescend- ing way to minister to people' and that seine organisations 'more or less throw the stuff at them and run'. Poor or destitute people 'should have a menu from which they can choose'. On the counter she keeps a red-backed credit book in which people are allowed to run up about £2 credit according to her knowledge of them. 'The rest of the world lives on Access and credit, so why shouldn't they?' The diners, some of whom arrived on the dot of 7 a.m, were more socially various than I had expected. Some were rootless homeless men, some were chronic alcoholics (only allowed in when sober), and apparently one-fifth are now homeless single people who are forced by social security regulations to 'move on' and who then return a few days later. There was a South African man in a green jacket, a woman with big earrings who seemed to be with a heavily-built man, and one diner in a tweed jacket, cavalry twills and brogues Was a Sparkian Man of Slender Means who ordered breakfast with a vaguely Oxford accent. (If you have finished with your paper, may I do the crossword?') While a frail Edinburgh gentlewoman wiped the tables, a very blue-eyed man went round the room longing for a chat. 'A man said tae me, "If I gie ye money ye'll only spend it on drink." So he went intae a shop and came oot wi' a bunch o'grapes.' Outside seagulls blown in from Leith dawdled and Yapped over Canongate. Like Meals on Wheels (a form of food welfare through which the voluntary sector keeps an unobstrusive eye on the elderly), Restaurants of the Heart may be one answer for single, childless and elderly People who need food and perhaps a little loose-knit companionship. But for people with children, the inability to provide proper' nourishing food is a source of maternal distress which only a suitable level of income can resolve. The double blow of food hardship and lack of cooking facilities for homeless people with children is particularly hard to bear.

On the baking pavements of Sussex Gardens, near Paddington, a young man marched up to greet me with an off-duty barracks' air of vest-on, boots-off. He turned out to be an ex-regular soldier (who had joined the army after leaving a north Wales children's home at the age of 17). With his Northern Irish wife and three children he has lived in bed-and-breakfast hotel rooms for three years ('this is our fifth hotel'). We entered a basement room about 12 feet square with a window which over- looked a dark high-walled yard (the chil- dren sleep in a room next door which even this July reeks of wet rot). When making this place home, one of Ted and Ann's first jobs was to scrape up domestic rubbish and used tampons thrown down into the yard from upper windows of the hotel and to put it in plastic bags. They then put up a small line on which to dry clothes and to which the hotel manager objects. That morning the breakfast dishes were neatly stacked in a washing-up bowl on top of a chest of drawers because the blue pedestal wash- basin in which they wash, clean their teeth, prepare food and do some laundry, had been thickly covered with white powder to destroy a plague of ants. There was a desire for cleanliness. The top of the windowsill, a coffee table and a miniature second-hand fridge (which had broken within days) were spread with folded pure white terry towels. Ann cooks as best she can with two or three items salvaged from the Northern Ireland council house they prematurely gave up when Ted got a security-man job plus a privately rented house (he thought) in Docklands. There is an electric kettle, a large square electric frying pan with a lid and a plug-in casserole known as a 'slow- crock'. They make stews in the slow-crock and when meat is too expensive the chil- dren like sausages at 55p a lb cooked in it with an onion and a packet of Paxo stuffing mix. Another very cheap stew is baked beans cooked with a tin of meat balls. Ann is fairly health-conscious and doesn't want the family to eat 'too much grease'. As shallow-frying chips in an unventilated basement bedroom in July is rather stifling, she shakes bought ones in kitchen paper to blot off the grease. Once their meal is ready, there is no table to sit round. The parents eat off their knees on the bed and

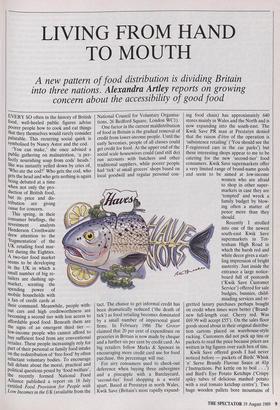

Food Fish* • Fresh fruit* Fresh vegetables* Poultry* Biscuits and cakes Vegetable oils* Bread — wholemeal* Whole milk Bread — white Meat products Sugar Butter *Indicates foods recommended in a healthy diet Source: National Food Surveys 1982 and 1986, HMSO 1984 and 1987

Relative price rises of recommended and less recommended foods, 1982-86.

Percentage price rise 1982-86 37 32 31 26 23 20 19 17 15 14 13 9

'I am happy to report much reduced tak-

the three children sit on the matted nylon carpet in front of them.

There are now three or four days a fortnight when Ted and Ann do not themselves eat, 'but we see the children never go without'. They survive on cups of tea and the occasional cheap Berkeley brand cigarette which they feel guilty about Out if I didn't have a cigarette living in this place, I'd go mad'). 'On days we don't eat we go to an aunt in Shepherd's Bush. We hope to get a cup of tea but, of course, we don't tell her we have no money. Some days she might offer us a meal.'

Their food cupboard is a narrow shelf at the top of a wardrobe. It contained some tins of Safeway baked beans, a tin of Marvel dried milk, a tub of Flora margar- ine, a white sliced loaf, Nescafe ('this is our luxury at £1.09 for a small jar') and several tins of Cadbury's Smash. Ted seized the Smash tin and explained why instant pow- dered potato is so important to them. When people live in one room they do not want to sleep at close quarters with real 'messy' vegetables (the better food is, the sooner it goes bad). With no separate place for food storage or preparation, processed package food gives some degree of neat- ness and control. It can be quickly mixed in a basin with boiling water from the kettle. (They have no means of boiling or steam- ing potatoes). 'Another reason we like Smash is because you get the container' with a tightly fitting plastic lid. Ted opened a Smash tin. At the bottom were several inches of granulated sugar, then a partition made from a piece of cardboard and then, on top of that, a deep layer of tea-bags. 'We know that when we're hitting this, we're in a real emergency.'

Later, Ann recalled in loving detail the 'salad baps' she had made for the children when she had a little money to spare. There had been a choice between a round floppy lettuce at 28p and a crisp 'iceberg' lettuce at 65p. Aware of the fact she was blowing almost 40p on a whim about lettuce, she went ahead in the Bayswater branch of Safeways and bought the ice- berg. 'Just because I'm homeless, I'm not common.'

Once upon a time, families in B&B hotels received an eating-out allowance of £1.55 for lunch and £1.55 for dinner (for each member of the family) to compensate for the fact they had poor cooking facilities and would have quite often to buy take- away meals. Since April, a typical couple with two children are now only permitted 61p per person per meal. Recently debat- ing this change in the Lords, Lord Skel- mersdale, speaking on the behalf of the Government, remarked:

The main point to remember is that meal allowances payable under the old rules were too generous . . . there will be occasions when it is not appropriate to have cooked meals all the time.

As the Nineties dawn morue a la Astor is on the menu.

Previous page

Previous page