WHAT KIND OF MAN WAS DRAKE?

A.L.Rowse reviews the character

and achievements of a West Country hero

FRANCIS Drake was a folk hero down here in the West Country, where I write, and there is a good deal of folklore about him still. But, of course, dull, disillusioned historians, like myself, have to stick to the facts. We have our uses: many years ago I was able to settle the year of his birth, hitherto unknown, as 1541.

Why was he the most famous English- man in the world in his time? How come? Those are the questions that take answer- ing.

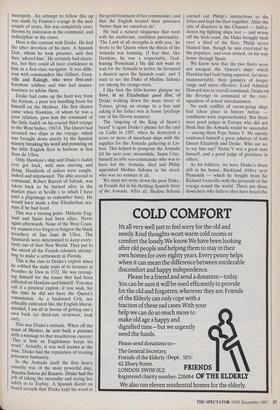

He earned his fame by the voyage around the world, 1577-80, on the whole the most famous in history, for Magellan after all died in the East Indies and never got back home. Drake did what Magellan did in getting through the Straits — in 16 days, the shortest passage of the century in those often impossible conditions. He did what Bartholomew Diaz had done in rounding the Cape of Good Hope, and what Vasco da Gama had done in crossing the Indian Ocean. All three in that one voyage — the more you know about it the more wonderful it becomes.

The Queen was the chief investor in the enterprise, and Drake sailed with her commission. And the Crown, not Drake, got the enormous swag from his capture of the treasure ship, Cacafuego. The Govern- ment spent it on keeping going resistance to Spain in the Netherlands, so that Philip II could never concentrate his resources on us. Elizabeth I graciously rewarded Drake with £10,000 out of the half-million he brought back and, it is said, another £10,000: that made him a rich man. She was in fact more generous than people have made out. Her motive in the enter- prise was clear. 'I would be revenged on the King of Spain for divers injuries that I have received at his hands,' she told Drake. 'But, of all men, my Lord Treasur- er must not know.'

This was her chief minister, Lord Bur- ghley, who had become more conservative with the years and was against challenging Spain's claim to a monopoly of the Pacific. It was indeed a challenge, and Drake had to bear the blame; for, as she told the ambassador when he came to protest, 'the gentleman careth not if I disavow him'.

But the voyage made such a sensation in the world that she resolved to recognise it and knighted him (that meant something then) in face of the world on board The Golden Hind at Deptford. She handed the sword for the ceremony to the French ambassador — just to inculpate the French a bit in the proceedings.

We cannot go in detail into the conse- quences — the immense addition to geog- raphical knowledge, exemplified by Mer- cator's map of the course of the circum- navigation; the plants and rarities brought back. One of his aims was to effect an entrance for England into the lucrative spice-trade, another Spanish-Portuguese monopoly. An attempt to follow this up was made by Fenton's voyage in the next couple of years; this was completely over- thrown by indecision in the command, and indiscipline in the crews.

Here is the contrast with Drake. He had the utter devotion of his men. A Spanish Don, whom he took prisoner, said that they 'adored him'. He certainly had charis- ma, but they could all have confidence in him as a first-class navigator. It was diffe- rent with commanders like Gilbert, Gren- ville and Raleigh, who were first-and- foremost soldiers and who had master- mariners to advise them.

Drake had come up the hard way from the bottom, a poor boy handling boats for himself on the Medway. His first chance came when Hawkins, of whom he was a poor relation, gave him the command of the little Judith on his crucial third voyage to the West Indies, 1567-8. The Queen had invested two ships in the voyage, which was brought down utterly by the Spanish viceroy breaking his word and pouncing on the little English fleet in harbour at San Juan de Ulloa.

Only Hawkins's ship and Drake's Judith ever got back, with men starving and dying. Hundreds of sailors were caught, lashed and imprisoned. The able second in command, Robert Barrett of Saltash, was taken back to be burned alive in the market place at Seville ( to which I have paid a pilgrimage to remember him). He would have made a fine Elizabethan sea- man if he had lived.

This was a turning point. Hitherto Eng- land and Spain had been allies. Never again afterwards. None of the West Coun- try seamen ever forgot or forgave the black treachery of San Juan de Ulloa. The Spaniards were determined to keep every- body out of their New World. They put to the sword all the French colonists attemp- ting to make a settlement in Florida.

This is the clue to Drake's exploit when he robbed the mule train of its treasure at Nombre de Dios in 1572. He was recoup- ing himself for the losses that had been inflicted on Hawkins and himself. You may call it a piratical exploit, if you wish, for this time he did not have the Queen's commission. As a backward Celt, not ethically cultivated like the English liberal- minded, I am all in favour of getting one's own back (so third-rate reviewers, look out).

This was Drake's attitude. When off the coast of Mexico, he sent back a prisoner with a message to that treacherous viceroy: This is how an Englishman keeps his word.' Actually, it was well known at the time, Drake had the reputation of treating prisoners humanely. In the Armada itself the first heavy casualty was of the most powerful ship, Nuestra Senora del Rosario. Drake had the job of taking the surrender and seeing her safely in to Torbay. A Spanish diarist on board records that Drake kept his word in the good treatment of her commander, and that the English treated their prisoners `better than we ourselves do'.

He had a natural eloquence that went with his exuberant, confident personality. `The Lord of all strengths is with you,' he wrote to the Queen when the threat of the Armada was looming. (I fear that, like Hawkins, he was a respectable, God- fearing Protestant.) He did not want to wait for the Armada to arrive; he favoured a descent upon the Spanish coast, and 'I trust to see the Duke of Medina Sidonia yet among his orange-trees.'

I like best the little-known glimpse we have, in an Elizabethan quod libet, of Drake walking down the main street of Totnes, giving an orange to a boy and asking if his father was at home (perhaps one of his Devon seamen).

The 'singeing of the King of Spain's beard' is again Drake's phrase for the raid on Cadiz in 1587, when he destroyed a score or more of merchant ships with the supplies for the Armada gathering at Lis- bon. This helped to postpone the Armada till the next year; meanwhile, Santa Cruz, himself an able sea-commander who was to have led the Armada, died and Philip appointed Medina Sidonia in his stead, who was no seaman at all.

We must not write down the poor Duke, as Froude did in his thrilling Spanish Story of the Armada. After all, Medina Sidonia carried out Philip's instructions to the letter and kept the fleet together. After the tale of disasters in the Channel — half-a- dozen big fighting ships lost — and worse off the Irish coast, the Duke brought back over a third of the fleet. Philip never blamed him, though he was execrated by the populace, and even stoned, on his way home through Spain.

We know now that the two fleets were not unequal, the 'Queen's ships' which Hawkins had built being superior, far more manoeuvrable, their gunnery of longer range and more effective. Lord Admiral Howard was in overall command, Drake on the Revenge in command of the rear- squadron of armed merchantmen.

No such conflict of ocean-going ships had taken place in history before conditions were unprecedented. But there were good judges in Europe who did not think that the Armada would be successful — among them Pope Sixtus V. He openly confessed himself a great admirer of both Queen Elizabeth and Drake. Who are we to say him nay? Sixtus V was a great man himself, and a good judge of greatness in others.

As for folklore, we have Drake's drum still in his house, Buckland Abbey near Plymouth — which he bought from Sir Richard Grenville with the proceeds of the voyage round the world. There are those down here who believe they have heard the drum beat when danger threatens the country. Believe it or not, some heard it at the surrender of the German fleet at Scapa Flow, after the First German War. And we can recite Newbolt's poem:

Drake he's in his hammock and a thousand mile away (Cap'n art tha sleepin' there below?)

I would rather have written that poem than I would Paradise Lost.

Previous page

Previous page