NEWBOLT FOR POETS' CORNER

Paul Webb calls for

a sterling English poet to be commemorated

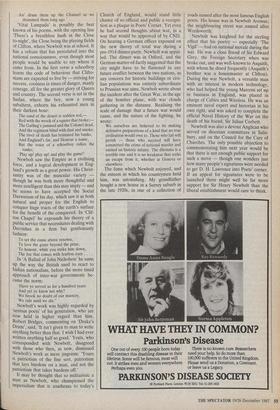

HENRY Newbolt deserves a memorial in Poets' Corner. When better than 1988, his 50th anniversary? He is a worthy candidate for a number of reasons. He was an immensely popular poet in his time (1862- 1938), and his first volume of verse, Admirals All, ran to 21 editions within a year. His next, The Island Race, was as successful. Although he was accused of writing verse which, though stirring, and full of 'swing and rattle', was essentially `rhetoric' and not real poetry, he was admired by the whole cross-section of English society. In his own words:

I could afford to smile [at the criticism] when I heard that men like Frederic Myers and Butler of Trinity and Leslie Stephen had been learning me by heart, and that in one expedition after another solidiers were carrying me in their knapsacks and reciting me round their camp fires. The time even came when Ministers quoted me in the House, and Bishops recited me in sermons

at St. Paul's before the King and Queen.

Newbolt's best known poems are con- cerned with the greatness of the Royal Navy, the public school ethos which his poems both represented and, to a remark- able degree created, and the Empire. He differed from the other great Imperial poet, Kipling, in that his heroes .tended to be clean-cut public school boys. In contrast to Kipling's fascination with the Indians, and their relationship with the Raj, New- bolt saw them as a servant race who could turn nasty — as in 'He Fell Among Thieves'. He wrote about 18th-century admirals, not Tommy Atkins, and he once referred, slightingly, to Kipling using 'the language of the street'. The nearest that Newbolt ever came to this was the Devon dialect that he used in one of his most famous poems, 'Drake's Drum'.

Drake he was a Devon man, an' ruled the Devon Seas, (Cap'n, art tha sleepin' there below?), Rovin' tho' his death fell, he went wi' heart at ease, An' dreaming arl the time o' Plymouth Hoe. `Take my drum to England, hang et by the shore, Strike et when your powder's runnin' low; If the Dons sight Devon, I'll quit the port o' Heaven, An' drum them up the Channel as we drummed them long ago.'

`Vital Lampada' is possibly the best known of his poems, with the opening line `There's a breathless hush in the Close to-night', the Close being the playing fields of Clifton, where Newbolt was at school. It has a refrain that has percolated into the national consciousness, even though most people would be unable to say where it came from. In the first verse a schoolboy learns the code of behaviour that Clifto- nians are expected to live by — striving for success, coolness in times of danger, manly courage, all for the greater glory of Queen and country. The second verse is set in the Sudan, where the boy, now a young subaltern, exhorts his exhausted men in their darkest hour:

The sand of the desert is sodden red,— Red with the wreck of a square that broke;— The Gatling's jammed and the Colonel dead, And the regiment blind with dust and smoke. The river of death has brimmed his banks, And England's far, and Honour a name, But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks; `Play up! play up! and play the game!'

Newbolt saw the Empire as a civilising force, and a logical development in Eng- land's growth as a great power. His Christ- ianity was of the muscular variety though he was both more thoughtful and more intelligent than this may imply — and he seems to have accepted the Social Darwinism of his day, which saw it as both natural and proper for the English to conquer huge tracts of the earth's surface for the benefit of the conquered. In 'Clif- ton Chapel' he expounds his theory of a public service that necessitates dealing with Dervishes in a firm but gentlemanly fashion:

To set the cause above renown, To love the game beyond the prize, To honour, while you strike him down, The foe that comes with fearless eyes . . .

In 'A Ballad of John Nicholson' he sums up the way the British used to react to Indian nationalism, before the more timid approach of inter-war governments be- came the norm:

`Have ye served us for a hundred years And yet ye know not why?

We brook no doubt .of our mastery, We rule until we die.'

Newbolt's work was highly regarded by `serious poets' of his generation, who are now held in higher regard than him. Robert Bridges, commenting on 'Drake's Drum', said, 'It isn't given to man to write anything better than that. I wish I had ever written anything half so good.' Yeats, who corresponded with Newbolt, disagreed with those who then, as now, dismissed Newbolt's work as mere jingoism: 'Yours is patriotism of the fine sort, patriotism that lays burdens on a man, and not the patriotism that takes burdens off.'

It may be thought that so militaristic a man as Newbolt, who championed the imperialism that is anathema to today's Church of England, would stand little chance of so official and public a recogni- tion as a plaque in Poets' Corner. Yet even he had second thoughts about war, in a way that would be approved of by CND. On hearing a German officer expound on the new theory of total war during a pre-1914 dinner-party, Newbolt was appal- led. The dinner was in Oxford, and the German matter-of-factly suggested that the city might have to be flattened in any future conflict between the two nations, as any concern for historic buildings or civi- lian populations was entirely subordinate to Prussian war aims. Newbolt wrote about the incident after the Great War, in the age of the bomber plane, with war clouds gathering in the distance. Realising the scale of damage that a future war would cause, and the nature of the fighting, he wrote:

We ourselves are believed to be making defensive preparations of a kind that no true civilisation would own to. Those who fail will perish — those who succeed will have committed the crime of national murder and earned an historic infamy. The dilemma is a terrible one and it is no weakness that seeks an escape from it, whether at Geneva or elsewhere.

The fame which Newbolt enjoyed, and the esteem in which his countrymen held him, was astonishing. My grandfather bought a new house in a Surrey suburb in the late 1920s, in one of a collection of roads named after the most famous English poets. His house was in Newbolt Avenue; the neighbouring street was named after Wordsworth.

Newbolt was knighted for the sterling effect that his poetry — especially 'The Vigil' — had on national morale during the war. He was a close friend of Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary when war broke out, and was well-known to Asquith, with whom he dined frequently (Asquith's brother was a housemaster at Clifton). During the war Newbolt, a versatile man with an interest in modern technology, who had helped the young Marconi set up in business in England, was placed in charge of Cables and Wireless. He was an eminent naval expert and historian in his own right, and was asked to complete the official Naval History of the War on the death of his friend, Sir Julian Corbett.

Newbolt was also a devout Anglican who served on diocesan committees in Salis- bury, and on the Council for the Care of Churches. The only possible objection to commemorating him next year would be that there is not enough public support for such a move — though one wonders just how many people's signatures were needed to get D. H. Lawrence into Poets' corner. If an appeal for signatures were to be launched there might well be far more support for Sir Henry Newbolt than the liberal establishment would care to think.

Previous page

Previous page