ARTS

Art

Ask a silly question

Giles Auty

My recent, unexpected appearance in the Sunday Times Magazine revealed to many, including professional colleagues, that I was formerly a painter. Some have been kind enough to ask me about this period. To amuse, rather than instruct, during a time of year when many galleries are closed, I have jotted down a few memories beginning, in the time-honoured tradition of chat shows, with some of my odder, but appropriately seasonal recollec- tions. (In the next issue I return to order with a review of Lucian Freud's important exhibition from the Pompidou in Paris.) When in my twenties I was possessor of an odd and inexplicable attraction for the mildly deranged. Wild-looking men or gesticulating women would regularly cross busy streets to harangue me. A personable and, so far as I knew, stable young woman once calmly informed me that we had been lovers in Egypt some 4,000 years earlier; should we not resume our former liaison more or less at once? Perhaps owing to a failure of memory on my part and conse- quent hesitation to accede instantly, she boarded an express train and set fire to a fellow passenger's luggage. A full exposi- tion of this story caused a fellow artist to fall from his ladder while we were painting the house of a further friend. I cannot laugh wholeheartedly because the young woman was returned to a place of treat- ment from which she had been on tempor- ary holiday. Such are the dilemmas of a young painter's life.

A more protracted acquaintance took place with an elderly man who, for some months, materialised regularly, about twi- light, at the door of my studio. The latter's preferred mode of conversation was to ask obscure or unanswerable questions which I suspected he worked out carefully between visits. If I made a fair stab at answering one, he would follow up keenly with a second. Given the location, one inevitable subject of our conversations was art, of which my visitor had little knowledge. I tried patiently to explain 'some of the theories then current; he was not so much disinclined as uninterested. Also he prefer- red to pursue his obsessive line of ques- tions. With misguided conceit, I imagined I could help him.

Lying awake recently, I remembered his demanding of me once why Christmases were getting worse — but on its own this would not have followed the bizarre logic of his oral constructions. These tended to follow an `if' and 'why' format, as in: 'If the buses are running on time, why are so many churches deserted?' You will get the general drift. Maybe the subject of the first part of the incomplete question referred to was art and had arisen at the time from my defence of contemporary theories. 'If art is getting better, why are Christmases getting worse?' is typical of his genre and is even the sort of question I could imagine asking myself, should I survive senility. Whatever the truth of its origin, this peculiar question has stuck in my mind since first recalling those talks with my strange old visitor.

Did I really believe once that 'art was getting better'? Thinking back, I recall my former, rather hesitant advocacy of the evolutionary theory of art possibly in rather the same way that a distinguished Spectator colleague may remember his socialism. In the early Sixties I lived in West Cornwall when the area was still a Mecca for aspiring young modernists. The fact that I subscribed somewhat half- heartedly to the 'onward and upward' theory of art may account for the sudden- ness of my conversion to a contrary view- point. Until some time early in 1963, certainly thought that art had at least some latent capacity to carry the flag forward through the courage of its innovators.

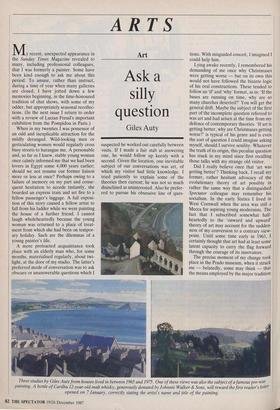

The precise moment of my change took place in the Prado museum, when it struck me — belatedly, some may think — that the means employed by the major tradition Three studies by Giles Auty from houses lived in between 1965 and 1975. One of these views was also the subject of a famous pre-war painting. A bottle of Cardhu 12-year-old malt whisky, generously donated by Johnnie Walker & Sons, will reward the first reader's letter opened on 7 January, correctly stating the artist's name and title of the painting. of European masters had greater, rather than lesser, expressive potential than those we were then using. By abandoning so many of their essential props, our contem- porary achievements were liable to be brave enough but limited by comparison. In seeking to rid ourselves of the inessen- tial detritus of the past, we had thrown away case after case of essential baggage. Admittedly the bathwater had gone, but where was the baby?

If modern art, like so many other aspects of contemporary life, is believed to be `better', why can the same not be said of the 'modern' Christmas? Perhaps what my old visitor was trying to say was that the future of art, like that of Christmas, lies in looking for the baby once more.

Previous page

Previous page