Crafts

Glass of the Caesars (British Museum, till 6 March)

The art of undercutting

Tanya Harrod

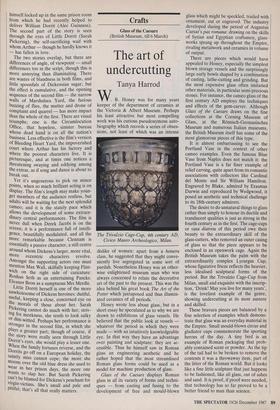

W. B. Honey was for many years keeper of the department of ceramics at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Perhaps his least attractive but most compelling work was his curious pseudonymous auto- biography which records a series of obses- sions, not least of which was an intense The Trivulzio Cage-Cup, 4th century AD, Civico Museo Archeologico, Milan.

dislike of women: apart from a hetaera class, he suggested that they might conve- niently live segregated in some sort of purdah. Nonetheless Honey was an other- wise enlightened museum man who was always concerned to relate the decorative art of the past to the present. This was the idea behind his great book The Art of the Potter which juxtaposed and thus illumin- ated ceramics of all periods.

Honey wrote less about glass, but in a short essay he speculated as to why we are drawn to exhibitions of glass vessels. He believed that the public look at vessels whatever the period in which they were made — with an intuitively knowledgeable eye. In that way they have an advantage over painting and sculpture: they are ac- cessible. Thus he himself saw in Roman glass an engineering aesthetic and he rather hoped that the most streamlined Roman glass forms could be used as a model for machine production of glass.

Glass of the Caesars displays Roman glass in all its variety of forms and techni- ques — from casting and fusing to the development of free and mould-blown glass which might be speckled, trailed with ornament, cut or engraved. The industry developed during the period of Augustus Caesar's pax romana: drawing on the skills of Syrian and Egyptian craftsmen, glass- works sprang up throughout the Empire, rivaling metalwork and ceramics in volume of output.

There are pieces which would have appealed to Honey, especially the simplest blown storage vessels and the surprisingly large early bowls shaped by a combination of casting, lathe-cutting and grinding. But the most expensive glass often imitatied other materials, in particular semi-precious stones. For instance, the cameo glass of the first century AD employs the techniques and effects of the gem-carver. Although Glass of the Caesars draws on the fine collections at the Corning Museum of Glass, at the Romisch-Germanisches Museum and numerous Italian museums, the British Museum itself has some of the most glamorous pieces of this type.

It is almost embarrassing to see the Portland Vase in the context of other cameo examples. Even the famous Blue Vase from Naples does not match it: the Portland Vase is a far finer example of relief carving, quite apart from its romantic associations with collectors like Cardinal del Monte and Sir William Hamilton. Engraved by Blake, admired by Erasmus Darwin and reproduced by Wedgwood, it posed an aesthetic and technical challenge to its 18th-century admirers.

The desire to do unnatural things to glass rather than simply to honour its ductile and translucent qualities is just as strong in the fourth century as in the first. The cage-cups or vasa diatreta of this period owe their beauty to the extraordinary skill of the glass-cutters, who removed an outer casing of glass so that the piece appears to be enclosed in an openwork cage. Again the British Museum takes the palm with the extraordinarily complex Lycurgus Cup, whose figurative frieze reflects the heavier, less idealised sculptural forms of the period. But the Trivulzio Cage-Cup from Milan, small and exquisite with the inscrip- tion, 'Drink! May you live for many years', is the loveliest example of the genre, showing undercutting at its most austere and skilled.

These bravura pieces are balanced by a fine selection of examples which demons- trate that glass was an everyday material in the Empire. Small mould-blown circus and gladiator cups commemorate the sporting heroes of the day. A tiny bird is an example of Roman packaging that prob- ably contained scent or powder. As the tip of the tail had to be broken to remove the contents it was a throwaway item, part of the litter of the Roman world. But it looks like a fine little sculpture that just happens to be fashioned, like all glass, out of ashes and sand. It is proof, if proof were needed, that technology has so far proved to be a better friend to man than science.

Previous page

Previous page