1941/A

by KINGSLEY AMIS

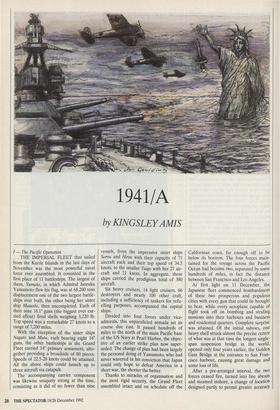

I — The Pacific Operation . . . THE IMPERIAL FLEET that sailed from the Kurile Islands in the last days of November was the most powerful naval force ever assembled. It consisted in the first place of 11 battleships. The largest of them, Yamato, in which Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto flew his flag, was at 68,200 tons displacement one of the two largest battle- ships ever built, the other being her sister ship Musashi, then uncompleted. Each of their nine 18.1" guns (the biggest ever car- ried afloat) fired shells weighing 3,220 lb. Top speed was a remarkable 27 knots to a range of 7,200 miles.

With the exception of the sister ships Nagato and Mutu, each bearing eight 16'' guns, the other battleships in the Grand Fleet carried 14" primary armament, alto- gether providing a broadside of 80 pieces. Speeds of 22.5-28 knots could be attained. All the above ships could launch up to three aircraft via catapult.

The accompanying carrier component was likewise uniquely strong at the time, consisting as it did of no fewer than nine vessels, from the impressive sister ships Soryu and Hiryu with their capacity of 71 aircraft each and their top speed of 34.5 knots, to the smaller Taigo with her 27 air- craft and 21 knots. In aggregate, these ships carried the prodigious total of 380 aircraft.

Six heavy cruisers, 14 light cruisers, 66 destroyers and nearly 100 other craft, including a sufficiency of tankers for refu- elling purposes, accompanied the capital ships.

Divided into four forces under vice- admirals, this unparalleled armada set its course due east. It passed hundreds of miles to the north of the main Pacific base of the US Navy at Pearl Harbor, the objec- tive of an earlier strike plan now super- seded. The change of plan had been largely the personal doing of Yamamoto, who had never wavered in his conviction that Japan could only hope to defeat America in a short war, the shorter the better.

Thanks to miracles of organisation and the most rigid security, the Grand Fleet assembled intact and on schedule off the Californian coast, far enough off to be below its horizon. The four forces main- tained for the voyage across the Pacific Ocean had become two, separated by some hundreds of miles, in fact the distance between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

At first light on 11 December, the Japanese fleet commenced bombardment of these two prosperous and populous cities with every gun that could be brought to bear, while every aeroplane capable of flight took off on bombing and strafing missions into their harbours and business and residential quarters. Complete surprise was attained. Of the initial salvoes, one heavy shell struck almost the precise centre of what was at that time the longest single- span suspension bridge in the world, opened only four years earlier, the Golden Gate Bridge at the entrance to San Fran- cisco harbour, causing great damage and some loss of life.

After a pre-arranged interval, the two forces ceased fire, turned into line abeam and steamed inshore, a change of location designed partly to permit greater accuracy and to conserve aircraft fuel, but also, at least as important, to leave the helpless cit- izens in no doubt of who and what it was that brought them destruction and death. The ships of the battle fleet went to their new stations and recommenced bombard- ment, whether of the cities themselves or of shipping and harbour and other installa- tions. The aerial attacks had continued without pause.

Shortly before 10.00 hours a tender or other small boat was observed approaching the water-borne forces bearing a rough- and-ready white flag. This impudent excur- sion, which could have claimed nothing conceivable in the way of legal standing or significance, was swiftly and properly dealt with. On orders of the Admiral himself, the destroyer Shimakaze closed with the intruder at top speed and rammed her amidships, cutting her clean in two. The remnants rapidly sank, those persons who had survived the impact being helped on their way by small-arms fire and grenades from Shimakaze's deck.

By then or soon afterwards, large parts of both cities and their outskirts were ablaze. Visibility on this clear, sunny win- ter's morning had at first been excellent; now heavy clouds of smoke drifted across the target and ascended hundreds of feet into the air. Massive explosions occurred at intervals. One especially severe and pro- longed disturbance in the San Francisco area has been taken to indicate a seismic shock induced by the bombardment in an area notoriously subject to earthquakes, but material evidence is lacking.

Despite increasing difficulties of ranging and targeting, the Japanese warships and warplanes prolonged their assault on the two coastal cities until breaking off the action shortly before noon. Already large parts of the afflicted areas had been destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of their people lay buried in the rubble or lay dead or dying in what had been their streets. Sentimentalists have suggested that the attack was needlessly prolonged and excessive damage and slaughter inflicted, perhaps forgetting the first objective of the Californian operation, viz, the delivery of the maximum possible shock, not only locally but throughout the United States. It could be asserted with some confidence, in the light of subsequent events, that those Americans who lost their lives in and around Los Angeles and San Francisco did so, albeit unknowingly, in the service of their country.

When the cease-fire came and all aircraft were safely returned, the fleet drew off. The whole of it, with one exception, began the long voyage home across the Pacific under the command of Vice-Admiral S. Toyoda. The exception, the giant battleship

Yamato, whose ammunition had been con- served, started off on her way to a fresh target some 3,500 miles to the south-east, a target of such importance that Admiral Yamamoto had insisted on attending to it personally.

The naval forces assaulting the Californi- an cities had met with negligible resistance. A number of obsolete US warplanes made feeble, unco-ordinated attempts to close with the vastly superior Japanese aerial armament, but in almost all cases these were shot out of the sky at ranges too great for them to return effective fire. Even con- sidered solely by the standards of warlike profit and loss, the Pacific operation was the most successful in history.

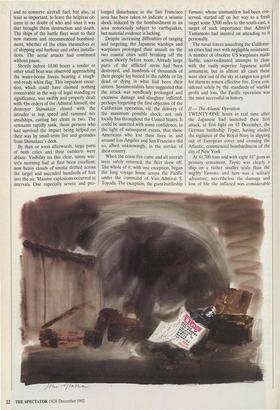

II — The Atlantic Operation TWENTY-ONE hours in real time after the Japanese had launched their first attack, at first light on 12 December, the German battleship Titpitz, having eluded the vigilance of the Royal Navy in slipping out of European cover and crossing the Atlantic, commenced bombardment of the city of New York.

At 41,700 tons and with eight 16" guns as primary armament, Tirpitz was clearly a ship on a rather smaller scale than the mighty Yamoto, and hers was a solitary adventure; nevertheless the damage and loss of life she inflicted was considerable

and bore closely upon events.

Tirpitz concentrated her fire on the island borough of Manhattan, though she caused some damage to the US Navy Yard on the farther side of the East River. Her shells destroyed or severely damaged sever- al of the city's loftier buildings, including the 102-storey Empire State Building. Two considerable fires were started. At a later stage, making up in boldness for what she lacked in fire-power, Titpitz actually sailed some distance up the Hudson, bombarding the shore at point-blank range with every gun available. A salvo from her secondary armament of 5.9" guns reduced the famous Statue of Liberty to fragments.

Amid growing but still largely ineffectual signs of resistance, Thpitz discontinued the action just before 09.00 hours and retired. Out in the North Atlantic once again she turned southward, her mission in that ocean not yet accomplished. While in tran- sit she successively launched from her cata- pult the four aircraft she carried, each of them an Arado 196A-3 twin-float seaplane carrying two 110-lb bombs. The two-man crews had been carefully selected and intensively trained for what was perhaps the most important part of the entire west- ern operational sector.

It had been decided with some reluc- tance that a regular naval attack on Wash- ington DC, though infinitely tempting, must be ruled out as too hazardous. Approach via the Potomac River or the Chesapeake Bay was finally rejected as too difficult and remote, with a risk that the encroaching force might be trapped and destroyed before it could withdraw. Such an outcome was unacceptable in view of the necessity that the enemy be denied any countervailing success, however small in proportion, on this day of his humiliation.

Accordingly, the four seaplanes delivered a short-range, low-level and deadly accu- rate attack on the White House on the late afternoon of a day that had filled it with Service and civilian chiefs of every descrip- tion.

No one who witnessed it would ever for- get the unheralded approach at nearly 100 yards per second of a warplane flaunting the insignia of a distant but hostile power and firing a machine-gun as it came. The story goes that one such round, penetrating a conference-room by its shattered window, struck the wheelchair in which President Franklin D. Roosevelt sat and, ricocheting, hit and killed an air-force general standing behind him. Whether literally true or not, the supposed incident has great metaphori- cal force.

After completing a number of strafing runs at their target, and having dropped on it their collective bomb-load, amounting to something not far short of half a ton of explosive, the seaplanes rendezvoused with the Tirpitz. Two airmen were lost. Those killed in and around the White House ran into scores, but the moral effect of such a daring stroke was incalculable. Now, by an assiduously reconnoitred route, Thpitz continued her long journey to the south. Round the tip of Florida she steamed through the Yucatan Channel between Cuba and Mexico, then down the Caribbean to her third and final objective.

HI — The Combined Operation DURING THE night of 16/17 December, Yamato and Thpitz took up their stations off the two ends of the Panama Canal, each vessel out of range of the shore defences. At a previously agreed time close to first light, both commenced bombardment of the sections of canal nearest them. After two hours the Thpitz, whose primary ammunition had started to run low, discon- tinued fire, and a little later Yamato fol- lowed suit.

There were altogether six double locks in the canal system, each of great mass and strength. All lock walls rested on rock foundations and were over 80 feet in height. In the case of the outermost locks, the walls contained over 2 million cubic yards of concrete. Nevertheless the concen- trated broadsides of the two great battle- ships caused multiple breaches in both. What with severe consequential flooding and damge to permanent installations, it was estimated from reports reaching the Washington office of the canal that, even under normal conditions, repair and reopening could be expected in months rather than weeks.

Before the preliminary investigations were complete, Yamato and Tirpitz had reached home and safety, having accom- plished their part in the shaping of history.

IV —The Sequel THE EMPIRE of Japan had declared war on the United States of America in a proclamation date-timed 11.30 p.m. on 11 December, but unfortunately delayed for some hours before it reached the US gov- ernment. At two o'clock that afternoon, Joachim von Ribbentrop, as foreign minis- ter, had read out to the American chargé d'affaires in Berlin the text of Germany's declaration of war.

The combatant powers continued in a state of war for seven full days. At 11 a.m. on 18 December, President Roosevelt delivered an address to both Houses of Congress and, by simultaneous radio broadcast, to the nation at large. The text ran, in part:

It is with a heavy heart, my fellow Americans, that I stand before you this day. You will all share my feelings of shock, sorrow and indig- nation at the appalling carnage that resulted from the Japanese surprise attack on the cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco. The German raids on the East Coast cities of New York and Washington, DC, though smaller in scale, were no less dreadful and demoralising. In the nation's capital I myself came under enemy fire, for a single instant only, but long enough to kindle in me a spe- cial sympathy with those men, women and children who really suffered.

America was still reeling from these heavy blows when the news arrived of the virtual destruction of the Panama Canal. That canal .. . is in a very real sense America's lifeline. Denied it, my Service heads advise me that the possibility of one day defeating in war two such powerful and such implaca- ble adversaries as Imperial Japan and the German Third Reich is not non-existent but is hopelessly small, far too small for the sub- stantial risk of total defeat to be run. There- fore, as your Commander-in-Chief, I hereby order all American forces to lay down their arms totally, finally and, forthwith, pending the signing of a peace treaty. My fellow Americans, the war is over!

Now, I call upon you all to join with me, at this late hour, in returning henceforth to our traditional path of neutrality amid foreign conflict. Let us forgo any thought of revenge and pursue the proud role of beacon of liber- ty and democracy, by whose light other nations may in the end return to the paths of peace and goodwill.

Necessary adjustments in the status of certain of our overseas territories, and in some of our domestic arrangements, are in the pro- cess of being settled and agreed. As soon as the details shall be finalised ...

The adjustments referred to by the Presi- dent turned out to comprise the cession to Japan of all America's Pacific territories, including the Hawaiian Group with the Pearl Harbor base, Guam and Wake Island, and to Germany of Puerto Rico, while the Panama Canal Zone passed under the tripartite authority of the United States, Japan and Germany. The domestic arrangements concerned were naval instal- lations in the continental United States. The US Navy was to be progressively reduced to fishery-protection and coast- guard vessels.

When these details were after some days released to the American public, some revulsion of feeling occurred, and there were riots and disturbances from ocean to ocean, though not as violent or prolonged as those that followed the original bom- bardments.

Besides, it was too late.

From A History of the Second Great War, 19391A-1943IA by Michael Bridgeman, Josef Goebbels Professor of Modern History in the University of Oxford.

Previous page

Previous page