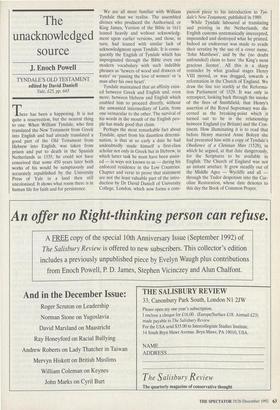

The unacknowledged source

J. Enoch Powell

TYNDALE'S OLD TESTAMENT edited by David Daniell Yale, £25, pp. 643 here has been a happening. It is not quite a resurrection, but the nearest thing to one. When William Tyndale, who first translated the New Testament from Greek into English and had already translated a good part of the Old Testament from Hebrew into English, was taken from prison and put to death in the Spanish Netherlands in 1535, he could not have conceived that some 450 years later both works of his would be sumptuously and accurately republished by the University Press of Yale in a land then still uncolonised. It shows what room there is in human life for faith and for persistence.

We are all more familiar with William Tyndale than we realise. The assembled divines who produced the Authorised, or King James, Version of the Bible in 1611 leaned heavily and without acknowledg- ment upon earlier versions, and those, in turn, had leaned with similar lack of acknowledgment upon Tyndale. It is conse- quently the English of Tyndale which has impregnated through the Bible even our modern vocabulary with such indelible phrases as 'hewers of wood and drawers of water' or 'passing the love of women' or 'a man after his own heart'.

Tyndale maintained that an affinity exist- ed between Greek and English and, even more, between Hebrew and English which enabled him to proceed directly, without the unwanted intermediary of Latin, from one vernacular to the other. The survival of his words in the mouth of the English peo- ple has made good that claim.

Perhaps the most remarkable fact about Tyndale, apart from his dauntless determi- nation, is that at so early a date he had undoubtedly made himself a first-class scholar not only in Greek but in Hebrew, in which latter task he must have been assist- ed — in ways not known to us — during his enforced residence in the Low Countries. Chapter and verse to prove that statement are not the least valuable part of the intro- duction by Dr David Daniell of University College, London, which now forms a corn-

panion piece to his introduction to Tyn- dale's New Testament, published in 1989.

While Tyndale laboured at translating and printing in the Netherlands, the English customs systematically intercepted, impounded and destroyed what he printed. Indeed an endeavour was made to evade their scrutiny by the use of a cover name, 'John Matthews', and by the (no doubt unfounded) claim to have 'the King's most gracious licence'. All this is a sharp reminder by what gradual stages Henry VIII moved, or was dragged, towards a reformation in the Church of England. We draw the line too starkly at the Reforma- tion Parliament of 1529. It was only in retrospect, looking back through the smoke of the fires of Smithfield, that Henry's assertion of the Royal Supremacy was dis- cerned as the breaking-point which it turned out to be in the relationship between England (or Britain) and the Con- tinent. How illuminating it is to read that before Henry married Anne Boleyn she had presented him with a copy of Tyndale's Obedience of a Christian Man (1528), in which he argued, at that date dangerously, for the Scriptures to be available in English. The Church of England was not an instant artefact. It grew steadily out of the Middle Ages — Wycliffe and all — through the Tudor despotism into the Car- oline Restoration, whose date denotes to this day the Book of Common Prayer.

Previous page

Previous page