The path of glory leads but to the grave

Penelope Lively

HOWARD CARTER: THE PATH TO TUTANKHAMUN by T.G.H. James Kegan Paul International, £24.95, pp. 443 hen I was a child in Egypt in the 1940s the discovery of the Tutankhamun tomb was some 20 years in the past. It was already a legend, but also such an abiding topic of conversation that I grew up under the distinct impression that my parents and their friends had excavated the tomb them- selves with their bare hands. The treasures reside today in Cairo Museum in a display which seems itself some kind of defiant time-warp — ancient glass cases, distinctly dusty, perfunctory labelling, not so much as a gesture in the direction of modish light- ing or trendy explanatory panels. They had to come to London, as they did in 1972, to get the full state-of-the-art-museum treat- ment. I find them more potent in Cairo's uncompromising presentation; the most powerful impact of all is that obtained from those cursory black-and-white snapshots of the jumbled interior of the tomb as it was first seen, like some bizarre and incredible attic junk-pile.

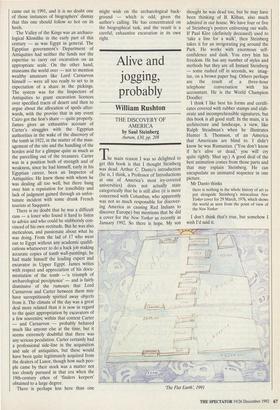

T.G.H. James is former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum and makes a sober, scholarly and painstaking biographer of a distinctly rum character. Howard Carter was the autodidact personified, a man who came accidentally to archaeology because he was good at drawing and happened to fall in with the right people at the right moment. He was not one of those towering figures of archaeology — a Schliemann or Mor- timer Wheeler — and had he not had the mixture of luck and tenacity to hit the greatest archaeological jackpot of all time he probably would rate little more than a few footnotes, never mind two full-scale biographies. The first, by H.V.F. Winstone, came out in 1991, and it is no doubt one of those instances of biographers' dismay that this one should follow so hot on its heels.

The Valley of the Kings was an archaeo- logical Klondike in the early part of this century — as was Egypt in general. The Egyptian government's Department of Antiquities had neither the funds nor the expertise to carry out excavation on an appropriate scale. On the other hand, museums the world over — not to mention wealthy amateurs like Lord Carnarvon himself — were all too ready to set to in expectation of a share in the pickings. The system was for the Inspectors of Antiquities to grant excavation licences over specified tracts of desert and then to argue about the allocation of spoils after- wards, with the proviso that in any event Cairo got the lion's share — quite properly. James gives an exhaustive account of Carter's struggles with the Egyptian authorities in the wake of the discovery of the tomb in 1922, in the matter of the man- agement of the site and the handling of the hordes avid for a glimpse quite as much as the parcelling out of the treasures. Carter was in a position both of strength and of weakness, since he had himself, early in his Egyptian career, been an Inspector of Antiquities. He knew those with whom he was dealing all too well, but there hung over him a reputation for irascibility and lack of judgment gained through an unfor- tunate incident with some drunk French tourists at Saqquara.

There is no doubt that he was a difficult cuss — a loner who found it hard to listen to advice and who could be stubbornly con- vinced of his own rectitude. But he was also meticulous, and passionate about what he was doing. From the lad of 17 who went out to Egypt without any academic qualifi- cations whatsoever to do a hack job making accurate copies of tomb wall-paintings, he had made himself the leading expert and excavator in Upper Egypt. James writes with respect and appreciation of his docu- mentation of the tomb —`a triumph of archaeological percipience' — and is fairly dismissive of the rumours that Lord Carnarvon and Carter between them may have surreptitiously spirited away objects from it. The climate of the day was a great deal more relaxed than it is now in regard to the quiet appropriation by excavators of a few souvenirs; within that context Carter — and Carnarvon — probably behaved much like anyone else at the time, but it seems extremely doubtful that there was any serious peculation. Carter certainly had a professional side-line in the acquisition and sale of antiquities, but these would have been quite legitimately acquired from the dealers of Luxor, though how such peo- ple came by their stock was a matter not too closely pursued in that era when the 19th-century ethos of 'finders keepers' obtained to a large degree.

There is perhaps less here than one might wish on the archaeological back- ground — which is odd, given the author's calling. He has concentrated on the biographical task, and the result is a careful, exhaustive excavation in its own right.

Previous page

Previous page