The cost of maintaining a front

Hugh Cecil

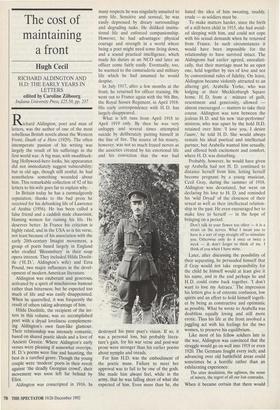

RICHARD ALDINGTON AND H.D: THE EARLY YEARS IN LETTERS edited by Caroline Zilboorg Indiana University Press, £25.50, pp. 237 Richard Aldington, poet and man of letters, was the author of one of the most rebellious British novels about the Western Front, Death of a Hero (1929). The often intemperate passion of his writing was largely the result of his sufferings in the first world war. A big man, with swashbuck- ling Hollywood-hero looks, his appearance did not immediately suggest vulnerability; but in old age, though still zestful, he had nonetheless something wounded about him. This remarkable collection of 92 of his letters to his wife goes far to explain why.

In Britain today he has a curmudgeonly reputation, thanks to the bad press he received for his debunking life of Lawrence of Arabia (1956). He has been called a false friend and a caddish male chauvinist, blaming women for ruining his life. He deserves better. In France his criticism is highly rated, and in the USA so is his verse, not least because of his association with the early 20th-century Imagist movement, a group of poets based largely in England who rivalled 'Bloomsbury' in their soap opera interest. They included Hilda Doolit- tle ('H. D.', Aldington's wife) and Ezra Pound, two major influences in the devel- opment of modern American literature.

Aldington was exuberant and generous, activated by a spirit of mischievous humour rather than bitterness; but he expected too much of life and was easily disappointed. When he quarrelled, it was frequently the result of others taking advantage of him.

Hilda Doolittle, the recipient of the let- ters in this volume, was an accomplished poet with a dryad loveliness complement- ing Aldington's own faun-like glamour. Their relationship was intensely romantic, based on shared poetic ideals and a love of Ancient Greece. Where Aldington's early verses were pleasing if somewhat overripe, H. D.'s poems were fine and haunting, the best in a rarefied genre. Though the young couple were 'modern' poets in their revolt against 'the deadly Georgian crowd', their movement was soon left far behind by Eliot.

Aldington was conscripted in 1916. In

many respects he was singularly unsuited to army life. Sensitive and sensual, he was easily depressed by dreary surroundings and degrading tasks. He disliked institu- tional life and enforced companionship. However, he had advantages: physical courage and strength in a world where being a poet might need some living down, and a sound practical intelligence, which made his duties as an NCO and later an officer come fairly easily. Eventually, too, he warmed to the camaraderie and military life which he had assumed he would despise.

In July 1917, after a few months at the front, he returned for officer training. He went out to France again with the 9th Btn, the Royal Sussex Regiment, in April 1918. His early correspondence with H. D. has largely disappeared.

What is left runs from April 1918 to April 1919 only. By then he was very unhappy and several times attempted suicide by deliberately putting himself in the line of fire. The source of his misery, however, was not so much frayed nerves as the anxieties created by his emotional life and his conviction that the war had destroyed his pure poet's vision. If so, it was a personal loss, but probably litera- ture's gain, for his war verse and post-war prose were stronger than his earlier poems about nymphs and oreads.

For him H.D. was the embodiment of the poetic muse. Failure to meet her approval was to fail to be one of the gods. She made him always feel, while in the army, that he was falling short of what she expected of him. Even more than he, she hated the idea of him sweating, muddy, crude — as soldiers must be.

To make matters harder, since the birth of a still-born child in 1915, she had avoid- ed sleeping with him, and could not cope with his sexual demands when he returned from France. In such circumstances it would have been impossible for the relationship to have survived intact. The Aldingtons had earlier agreed, unrealisti- cally, that their marriage must be an open one, held together by ties of love and not by conventional rules of fidelity. On leave, Aldington became violently attracted to an alluring girl, Arabella Yorke, who was lodging at their Mecklenburgh Square home. H. D, from a mixture of guilt, resentment and generosity, allowed — almost encouraged — matters to take their course. Aldington was torn between the jealous H. D. and his new `star-performer' mistress, who was upset by the hold H.D. retained over him: `I love you, I desire l'autre,' he told H. D. She would always remain his ideal poetical and intellectual partner, but Arabella wanted him sexually, and offered both excitement and comfort, where H. D. was disturbing.

Probably, however, he would have given up Arabella had not H. D. continued to distance herself from him, letting herself become pregnant by a young musician, Cecil Gray, during the summer of 1918. Aldington- was devastated, but went on declaring his love to H. D. and reminded his 'wild Dryad' of the closeness of their sexual as well as their intellectual relation- ship in the past. He even encouraged her to make love to herself — in the hope of bringing on a period:

Don't talk to your flower too often — it is a strain on the nerves. What I mean you to have is a sort of orgy straight off to stimulate you. Otherwise only do it once or twice a week — & don't forget to think of me. I think of you when I have mine.

Later, after discussing the possibility of their separating, he persuaded himself that if Gray would not take responsibility for the child he himself would at least give it his name, and in the end perhaps he and H. D. could come back together. 'I don't want to lose my Astraea.' The impression his letters give is of extreme confusion, low spirits and an effort to hold himself togeth- er by being as constructive and optimistic as possible. What he wrote to Arabella was doubtless equally loving and still more erotic. Thus his life at the front involved a juggling act with his feelings for the two women, to preserve his equilibrium.

Like most of his fellow soldiers late in the war, Aldington was convinced that the struggle would go on well into 1919 or even 1920. The Germans fought every inch; and advancing over old battlefield areas could sometimes be a horrific rather than an exhilarating experience:

The utter desolation, the ugliness, the sense of misery, the regret of all our lost comrades.

When it became certain that there would

be peace in a few days, he dared at last to hope that his pre-war sensibilities might return:

It does not matter if I must hold out my hand for bread to my inferiors, if I must be a beg- gar. At least I shall be free & perhaps my lost dreams will come home to me. 0 to see with clear unafraid eyes once more the calm light, upon calm waters, sun, wind, & trees and the ecstasy of beauty, the presence of the gods.

He was demobilised in mid-February 1919. The noble emotions of self-sacrifice he had felt towards his wife began to dis- solve in bitterness as the need to keep up a façade evaporated. Shell-shocked, he was overcome with irrational anger — no mood in which to confront the consequences of the emotional mess which was partly its cause. H. D's baby was born, but Gray showed no interest in accepting father- hood, and soon Aldington wanted nothing to do with it either. He violently rejected his wife, feeling that she had rejected him. He set up house with Arabella, but remained half in love with H. D., though they did not meet for another ten years.

At the time of their parting, H. D. was already deeply involved with a younger woman, Winifred Ellerman. Once again she had found, as so often in her life, a new source of emotional support. She was like some fine-tuned, brittle machine, requiring the attention of a skilled mechanic to keep it functioning — though it was often more resilient than the chosen attendants. Aldington may have been a casualty of the war, but he was also a casualty of H. D.

Dr Zilboorg has done a great service by getting Aldington's moving and vivid letters into print and in telling, fully and dis- passionately, the story behind them. Her footnotes are excellent, though I had the occasional query: the 'William Wallace' referred to by Aldington is surely the national hero of 'Scots wha hae' fame, not the Victorian philosopher; and the 'Anti- nous' to whom H. D. compared her hus- band must be Hadrian's peerless Bithynian lover, rather than the more obscure suitor of Penelope. But this is a fascinating book, expertly presented.

Previous page

Previous page