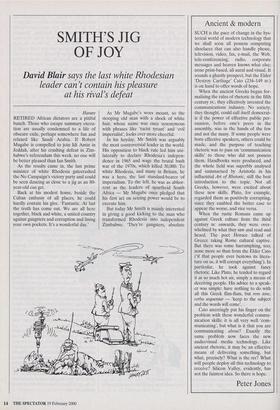

SMITH'S JIG OF JOY

David Blair says the last white Rhodesian

leader can't contain his pleasure at his rival's defeat

Harare RETIRED African dictators are a pitiful bunch. Those who escape summary execu- tion are usually condemned to a life of obscure exile, perhaps somewhere fun and relaxed like Saudi Arabia. If Robert Mugabe is compelled to join Idi Amin in Jeddah, after his crushing defeat in Zim- babwe's referendum this week, no one will be better pleased than Ian Smith.

As the results came in, the last prime minister of white Rhodesia gatecrashed the No Campaign's victory party and could be seen dancing as close to a jig as an 80- year-old can get.

Back at his modest home, beside the Cuban embassy of all places, he could hardly contain his glee. 'Fantastic. At last the truth has come out. We are all here together, black and white, a united country against gangsters and corruption and lining your own pockets. It's a wonderful day.' As Mr Mugabe's woes mount, so the stooping old man with a shock of white hair, whose name was once synonymous with phrases like 'racist tyrant' and 'evil imperialist', looks ever more cheerful.

In his heyday, Mr Smith was arguably the most controversial leader in the world. His opposition to black rule led him uni- laterally to declare Rhodesia's indepen- dence in 1965 and wage the brutal bush war of the 1970s, which killed 30,000, To white Rhodesia, and many in Britain, he was a hero, the last standard-bearer of imperialism. To the left, he was as abhor- rent as the leaders of apartheid South Africa — Mr Mugabe once pledged that his first act on seizing power would be to execute him.

But today Mr Smith is mainly interested in giving a good kicking to the man who transformed Rhodesia into independent Zimbabwe. 'They're gangsters, absolute gangsters, running a one-party communist dictatorship,' is his succinct summary of Mr Mugabe's government. 'They've man- aged to ruin a wonderful country. Young blacks come to see me and say, "Our chil- dren are going to bed hungry." Now, that's a terrible thing, terrible.'

Mr Smith takes a grim delight in pre- dicting a bleak future for Mr Mugabe, now that Zimbabwe's opposition has finally got its act together. 'He's clinging on, because when he loses power people will start ask- ing questions and he'll be in big trouble. It will all come out; he's been lining his own pockets, corruption, gangsterism, it's mon- strous. He's like a wounded, cornered ani- mal.'

But after 20 years of Mr Mugabe's `gangsterism', Mr Smith lives quietly in a northern suburb of Harare and still owns a large farm. He attacks the government at any excuse, yet no action is taken against him. Doesn't this show Mr Mugabe's remarkable magnanimity? Mr Smith glares at me: 'We've always had freedom in this country. Of course I have the right to speak out, just as people had the right to speak out when I was prime minister.' Actually, Mr Mugabe was jailed for ten years after speaking out against white rule, but the penetrating stare from Mr Smith's blue eyes deters me from pressing the point. Instead, I ask him about his mem- oirs, The Great Betrayal, which blame a bewildering array of British politicians for the collapse of white Rhodesia. In the Smith version of history, Lord Carrington wins the title of Chief Betrayer, the man who fired the bullet that killed Rhodesia, for chairing the Lancaster House Conference in 1979 that led to independence for Zimbabwe and Mr Mugabe's sweeping victory in the first elec- tions in 1980.

Mr Smith's hatred for Carrington bor- ders on the hysterical. 'Carrington, errrrr, Carrington. I've met some pretty shady people in my time, but Carrington was the most two-faced of the lot.' According to the Smith version of events (denied by everyone else) Carrington gave him a pri- vate guarantee that Lancaster House would not result in Mr Mugabe coming to power. When precisely that happened, Mr Smith decided that the agreement was 'a stitch-up, a complete put-up job'. It became the focus of all his withering scorn. `We watched all that we had fought for being taken away. That deal meant we would be run by a bunch of communist gangsters. I was violently opposed to Lan- caster House. I hated everything to do with that damn conference. I warned them what would happen.' Central to Mr Smith's burning sense of betrayal is his conviction that Britain tossed aside her most loyal subjects. 'We Rhodesians were more British than the British, and we were proud of that. We were brought up to respect the Union Jack. When the National Anthem was played, we had to stand up straight and stop fidgeting. That was the pioneer spirit.' During the war, Rhodesia did more than any other colony to help the mother coun- try, and the young Ian Smith was no excep- tion. Joining 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron, he was shot down over Italy in 1944 and spent five months with the partisans (`great chaps'), ambushing Germans and drinking vast amounts of red wine Ca very happy time'). Then he escaped over the Alps into France, where the allies had just landed. `You had to go home if you had been behind the lines for more than three months. But I was desperate to keep on flying.' Flight Lieutenant Smith had his wish and finished the war in Germany with 130 Squadron. Mr Smith's nostalgia for the war is undisguised — his walls are covered with paintings of Spitfires and a copy of Reach for the Sky has pride of place beside his armchair. How did he feel when it was all over? 'Very disappointed. I wanted to get a bit more out of those damned Germans who had killed so many of my friends. It was a shame we didn't carry on the war against those damned communists. Com- munism, fascism, they're both the same.' After crashing a Hurricane in 1943, Mr Smith's face was surgically rebuilt — one eye is round and intense, the other is nar- row and intense. Both fixed me with a steely gaze.

But why had a people so proud of their Britishness rebelled against the crown by declaring independence? 'It was the march of communism down the African continent. We had to stop it. We weren't prepared to just sit back and accept it, having seen the disasters to the north of us, having seen what happened when the Belgians pulled out of the Congo and the white settlers were massacred. So we decided to make a stand.' Once again, that steely gaze.

UDI galvanised black nationalism and by 1972 guerrilla armies led by Mr Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo were mounting regular attacks. Did UDI achieve anything? Mr Smith's flat Rhodesian tones echoed among the Spitfires. 'We saved the situa- tion for an extra 15 years. UDI got us 15 fabulous years.'

Fabulous? What about the war? His intense gaze became positively com- bustible. 'We had the greatest national spirit in the world, a fantastic country, great race relations, the happiest black faces in the world. We had a booming economy, despite those British sanctions, and we were the only country where crime was falling. OK, we had a war, but we were getting on top of it. If our friends hadn't betrayed us, we would have won.'

Yet the final result of UDI was that white Rhodesians were landed with a deal that removed all traces of their political influence and brought a man they abhorred into power. As Mr Smith crows over Zimbabwe's catalogue of disasters, he might reflect that arguably he did more than anyone else to bring Mr Mugabe to power.

David Blair is Harare correspondent of the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page