ARTS

Theatre 1

With eyes as big as saucers

Beryl Bainbridge recalls life back- stage at the Liverpool Playhouse, now threatened with closure

the Star Theatre, opened on 11 November 1911. It wasn't as if the city was starved of

theatrical entertainment: there was the Royal Court, the Empire, the Tivoli, Queen's, the Shakespeare, the Rotunda and Kelly's Theatre in Paradise Street. In that year the season at the Court included productions of Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird, The Chocolate Soldier, A Butterfly on the Wheel and Old Kentucky, the last with a burning stable, six horses and a brass band on stage. Two years before, some- what ominously, the audience at the Tivoli had been riveted by 'Mr Jasper Redfern's series of remarkable moving pictures'.

On the first night at the Playhouse the curtain went up on a performance of The Admirable Crichton, but not before Aida Jenoure, majestically representing Mrs Siddons as the Tragic Muse, had declaimed an ode especially written for the occasion by John Masefield, which began:

Here in this house tonight, our city makes Something which must not fail for our sakes, For we begin what men have been too blind To build elsewhere, a temple for the mind . . . .

Considering the number of 'temples' dotted all over the city the poem appears rather inaccurate, but it apparently went down very well on the night. The next day some of the newspapers had a field day prophesying disaster: 'The Directors of the Repertory Theatre have plunged headlong into a morass of troubles and embarrass- ment out of which we sincerely hope they will bob up with smiles on their faces and six per cent in their hands.' In the event, although it wasn't all plain sailing, such gloomy pessimism was proved wrong and the Playhouse has survived for 80 years.

It may not do so for much longer; on 8 January this year the theatre was granted an Administration order by the High Court in Manchester. This in effect means that if it cannot pay its debts by the end of March it will close. The city council, if it chose, could then rip out its seats and turn it into a night club.

I was a member of the Playhouse Com- pany from 1949 to 1952. It was my mother's idea that I should go on the stage; I would have preferred to be a mortuary attendant. At five I was treading the boards as a member of Miss Thelma Bickerstaff's Tiny Tots ensemble, dancing for the troops at the Garrison Theatre, Southport. I also sang 'Kiss Me Good- night, Sergeant Major'. It wasn't that my mother was stage-struck, rather that she had a sixth sense I was going to turn out both scholastically dim and temperamen- tally unstable. The interior of the Liverpool Playhouse, recently restored to its former glory I was employed by the Playhouse — for nothing a week — as an assistant stage manager and character juvenile. My duties consisted of sitting in the prompt corner with the book, understudying, fetching sandwiches from Brown's cafe in William- son Square, holding packs of ice to the forehead of the leading lady and helping with the props. I was also expected to be present at costume fittings and be handy with the tape measure — the noting of distance between shoulder and elbow was uneventful, but knee to crotch was a nightmare. In the green room I listened to terrible stories of hardship, of conversion to Catholicism, of sexual despair. At second hand I trod the pavements looking for work, was discarded by brutal lovers, dazzled by the ritual of the Mass.

That first season I played a boy mathe- matical genius — that was one in the eye for my mother — the Dog with Eyes as Big as Saucers in The Tinder Box, a serving wench in a Restoration comedy, and a lady-in-waiting in Richard II. I hardly knew who I was. I had no identity of my own because I was bewitched by those characters, both real and imaginary, among whom I lived. At night, when I had washed out the glasses and put away the props, I ran, as though carrying the good news from Ghent to Aix, to catch the last train home to Formby, pursued by de- mons. Beside me sprinted the Earls of Bushy, Bagot and Green, 'those villains, vipers, dammed without redemption'. We fled up Stanley Street four abreast, past the joke shop with the rubber masks grinning behind the glass, past the chemist's with its whirling spray stuck like a red-hot poker in the window, and behind us pounded the butcher Mowbray, Thomas, Duke of Nor- folk.

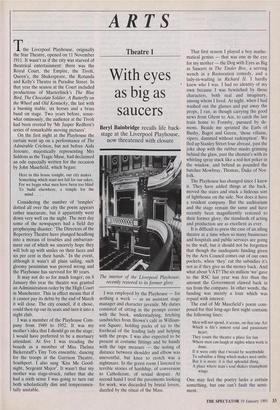

The Playhouse has changed since I knew it. They have added things at the back, moved the stairs and stuck a hideous sort of lighthouse on the side. Nor does it have a resident company. But the auditorium and the stage remain the same and have recently been magnificently restored to their former glory; the standards of acting and production are as excellent as ever.

It is difficult to press the case of an ailing theatre at a time when so many businesses and hospitals and public services are going to the wall, but it should not be forgotten that though the inadequate funding given by the Arts Council comes out of our own pockets, when 'they' cut the subsidies it's not as if they give us the money back. And what about VAT? The six million 'we' gave to the RSC last year was less than the amount the Government clawed back in tax from the company. In other words, the funding was merely a loan which was repaid with interest.

The end of Mr Masefield's poem com- posed for that long-ago first night contains the following lines:

Men will not spend, it seems, on that one Art Which is life's inmost soul and passionate heart;

They count the theatre a place for fun Where men can laugh at nights when work is done.

If it were only that t'would be worthwhile To subsidise a thing which makes men smile; But it is more: it is that splendid thing, A place where man's soul shakes triumphant wings. . . .

One may feel the poetry lacks a certain something, but one can't fault the senti- ment.

Previous page

Previous page