The Treasury gives up on candle—ends and becomes a Roman candle

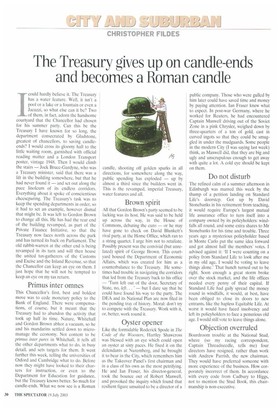

1 could hardly believe it. The Treasury has a water feature. Well, it isn't a pool or a lake or a fountain or even a Jacuzzi, so what else can it be? Two of them, in fact, adorn the handsome courtyard that the Chancellor had chosen for his summer party. Can this be the Treasury I have known for so long, the department consecrated by Gladstone, greatest of chancellors, to saving candleends? I would cross its gloomy hall to the little waiting room, garnished with official reading matter and a London Transport poster, vintage 1948. Then I would climb the stairs — Jock Bruce-Gardyne, who was a Treasury minister, said that there was a lift in the building somewhere, but that he had never found it — and set out along the puce linoleum of its endless corridors. Everything about it spoke of conscientious cheeseparing. The Treasury's task was to keep the spending departments in order, so it had to set an example, however dismal that might be. It was left to Gordon Brown to change all this. He has had the rear end of the building revamped, as part of the Private Finance Initiative, so that the Treasury now faces north across the park and has turned its back on Parliament. The old rabbit-warren at the other end is being revamped in its turn and will then house the united tax-gatherers of the Customs and Excise and the Inland Revenue, so that the Chancellor can keep an eye on them. I just hope that he will not be tempted to keep an eye on my tax return.

Primus inter omnes

This Chancellor's first, best and boldest move was to cede monetary policy to the Bank of England. There were compensations, of course. but it meant that the Treasury had to abandon the activity that took up half its time. Nature, Whitehall and Gordon Brown abhor a vacuum, so he and his mandarins settled down to micromanage the economy. Not content to be primus inter pares in Whitehall, it tells all the other departments what to do, in busy detail, and sets targets for them. It went further this week. telling the universities of Oxford and Cambridge what to do. Before now they might have looked to their charters for instruction, or even to the Department for Education for guidance, but the Treasury knows better. So much for candle-ends. What we now see is a Roman candle, shooting off golden sparks in all directions, for somewhere along the way, public spending has exploded — up by almost a third since the builders went in. This is the revamped, imperial Treasury, water features and all.

Brown spirit

All that Gordon Brown's party seemed to be lacking was its host. He was said to be held up across the way, in the House of Commons, debating the euro — or he may have gone to check on David Blunkett's rival party, at the Home Office, which ran to a string quartet. I urge him not to retaliate. Possibly present was the convivial (but unrelated) spirit of George Brown. This courtyard housed the Department of Economic Affairs, which was created for him as a counterbalance to the Treasury. He sometimes had trouble in navigating the corridors that led from the Treasury back to his office — 'Turn left out of the door, Secretary of State, no, left.. — but I dare say that he could have found his way to the party. The DEA and its National Plan are now filed in the pending tray of history. Moral: don't try to compete with the Treasury. Work with it, or, better, work round it.

ster opener

Like the formidable Roderick Spode in The Code of the Woosters, Hartley Shawcross was blessed with an eye which could open an oyster at sixty paces. He fixed it on the defendants at Nuremberg, and he brought it to bear in the City, which remembers him as the Takeover Panel's first chairman and in a class of his own as the most petrifying. He and Ian Fraser, his director-general, took the bounce out of Robert Maxwell, and provoked the inquiry which found that resilient figure unsuited to be a director of a public company. Those who were gulled by him later could have saved time and money by paying attention. Ian Fraser knew what to expect. In post-war Germany, where he worked for Reuters, he had encountered Captain Maxwell driving out of the Soviet Zone in a pink Chrysler, weighed down by three-quarters of a ton of gold, cast in curved ingots so that they could be smuggled in under the mudguards. Some people in the modern City (I was saying last week) think, as Maxwell did, that they are big and ugly and unscrupulous enough to get away with quite a lot. A cold eye should be kept on them.

Do not disturb

The refined calm of a summer afternoon in Edinburgh was marred this week by the thump of a petition landing on Standard Life's doorstep. Got up by David Stonebanks in his retirement from teaching, it would require Europe's largest mutual life assurance office to turn itself into a company owned by its policyholders: windfalls all round, and some extra shares to Mr Stonebanks for his time and trouble. Three years ago a mysterious policyholder based in Monte Carlo put the same idea forward and got almost half the members' votes. I advised against it: If I were counting on a policy from Standard Life to look after me in my old age, I would be voting to leave things alone.' That hunch turned out to be right. Soon enough a great storm broke over the stock market, and the life offices needed every penny of their capital. If Standard Life had gaily spread the money round in windfalls, it would, at best, have been obliged to close its doors to new entrants, like the hapless Equitable Life. At worst it would have faced insolvency and left its policyholders to face a penurious old age. I would still vote to leave things alone.

Objection overruled

Boardroom trouble at the National Stud, where (so my racing correspondent, Captain Threadneedle, tells me) four directors have resigned, rather than work with Andrew Parrish, the new chairman. They would have preferred someone with more experience of the business. How corporately incorrect of them. In accordance with every code from Cadbury to Higgs, not to mention the Stud Book, this chairmanship is non-executive.

Previous page

Previous page