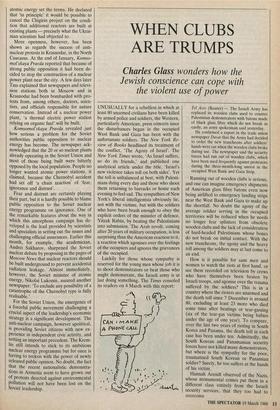

WHEN CLUBS ARE TRUMPS

Charles Glass wonders how the

Jewish conscience can cope with the violent use of power

UNUSUALLY for a rebellion in which at least 80 unarmed civilians have been killed by armed police and soldiers, the Western, particularly American, press concern since the disturbances began in the occupied West Bank and Gaza has been with the unfortunate soldiers. The New York Re- view of Books headlined its treatment of the conflict, 'The Agony of Israel'. The New York Times wrote, 'As Israel suffers, so do its friends,' and published one analytical article under the title, 'Israel's new violence takes toll on both sides'. Yet the toll is unbalanced at best, with Palesti- nians dying every day and those who shoot them returning to barracks or home each evening to feel sad. The sympathies of New York's liberal intelligentsia obviously lie, not with the victims, but with the soldiers who have been brash enough to obey the explicit orders of the minister of defence, Yitzak Rabin, by beating the Palestinians into submission. The Arab revolt, coming after 20 years of military occupation, is less surprising than the American reaction to it, a reaction which agonises over the feelings of the occupiers and ignores the grievances of the occupied.

Luckily for those whose sympathy is reserved for the young men whose job it is to shoot demonstrators or beat those who might demonstrate, the Israeli army is at last doing something. The Times consoled its readers on 4 March with this report:

Tel Aviv (Reuter) — The Israeli Army has replaced its wooden clubs used to counter Palestinian demonstrators with batons made of black glass fibre which do not break as easily, an army spokesman said yesterday.

He confirmed a report in the trade union newspaper Davar that the Army had decided to order the new truncheons after soldiers' hands were cut when the wooden clubs broke during use. The newspaper said the security forces had run out of wooden clubs, which have been used frequently against protestors during the three-month-long unrest in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Running out of wooden clubs is serious, and one can imagine emergency shipments of American glass fibre batons even now being airlifted to emergency landing strips near the West Bank and Gaza to make up the shortfall. No doubt the agony of the average soldier serving in the occupied territories will be reduced when he needs no longer fear splinters from obsolete wooden clubs and the lack of consideration of hard-headed Palestinians whose bones do not break on initial contact. With the new truncheons, the agony and the heavy toll among the soldiers may at last come to an end.

How is it possible for sane men and women to watch the riots at first hand, or see them recorded on television by crews who have themselves been beaten by Israeli troops, and agonise over the trauma suffered by the soldiers? This is in a country where the rioters are unarmed and the death toll since 7 December is around 80, excluding at least 23 more who died some time after beatings or tear:gassing (six of the tear-gas victims being babies under the age of one year). To compare, over the last two years of rioting in South Korea and Panama, the death toll in each case has been under ten. Admittedly, the South Korean and Panamanian security forces have not killed many demonstrators, but where is the sympathy for the poor, traumatised South Korean or Panamian soldier? Surely, he too suffers at the hands of his victim.

Hannah Arendt observed of the Nazis, whose monumental crimes put them in a different class entirely from the Israeli security services, that they too had to overcome

not so much conscience as the animal pity by which all normal men are affected in the presence of physical suffering. The trick used by Himmler — who apparently was rather strongly afflicted with these instinctive reac- tions himself — was very simple and prob- ably very effective; it consisted in turning these instincts around, as it were, in directing them towards the self. So that instead of saying: What horrible things I did to people! the murderers would be able to say: What horrible things I had to watch in the pur- suance of my duties, how heavily the task weighed upon my shoulders! (Eichmann in Jerusalem, Viking, 1965, page 106)

Compare this to Golda Meir's famous observation after the 1967 war: 'We may some time be able to forgive the Arabs for killing us, but we will never forgive them for forcing us to kill them.'

The Holocaust survivor Primo Levi wrote in his masterpiece describing surviv- al in Auschwitz of the Nazis who tor- mented him and his fellow Jews that If we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listen, they will not understand'. Who is listening to the Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza? Who, if he listens, will understand them? What are they saying?

They are saying loudly and clearly they do not want to be ruled by Israelis, they do not want foreign settlers on their land and they, for good or ill, want to rule them- selves. To achieve their demands, they would prefer to negotiate, through their chosen representatives, but denial of this option forces them to fight. How little we hear their angry voices, and how much we read of the options facing Israel. In one of the better British weeklies, the Tablet, its Israel correspondent, a liberal and humane writer and encyclopaedist named Geoffrey Wigoder, presented the alternatives for the Israeli leadership. In an article entitled 'Crisis in Israel' on 6 February, Wigoder wrote, `The last few weeks have brought Israelis face to face with the truth.'

He said both sides would have to make concessions for peace. 'So, what should be done?' he asked. He raised five possible courses of action:

Hold tight in the hope that the uprising will wear itself out? . . . Get rid of the territor- ies? Few Israelis would support such a solution, especially in view of the dangers to security that would ensue . . . Organise a mass emigration of Arabs, mainly to Jordan? . . Agree to some sort of autonomy for the Arabs in the territories? . . . Seek a solution within the framework of a comprehensive peace settlement to be discussed at an international conference? This proposal, energetically pushed by the leader of the Labour Party and deputy premier, Shimon Peres. is bitterly opposed by his coalition partners. In view of the many doubts and risks involved, it is unlikely that it would receive widespread backing and it could lose Peres the next election: at the moment, it seems a non-starter.

Dr Wigoder admitted that each course was fraught with difficulties, practical or moral. One wonders, however, how some of these questions can be asked at all. If the moral import of some of them is lost on Western readers, even the concerned Catholic readers of the Tablet; it might be best to imagine for a moment a future in which the Palestinians have obtained their state in the West Bank and Gaza. They achieve military superiority over their Israeli neighbours, whom they attack at will, much as the Israelis freely attack Lebanon today. The Israelis launch feeble commando attacks on Palestinians in Ramallah and East Jerusalem, and the Palestinian state, aided by the Soviet Un- ion as Israel is today aided by the US, decides to occupy Israel proper. In a lightning offensive which takes all of, let us say, six days, the tiny Palestinian state moves its borders north, south and west to include all of Israel — using the pretext of some Israeli provocation. Arabs all over the Near East, America and Europe re- joice and feel a new pride in their heritage — military prowess for some strange reason giving them self-respect where their culture did not.

The long process of occupying cities, towns and villages begins. Ruling unjustly, as most occupiers do, the Palestinian army faces increasing bitterness from Israeli civilians. Palestinian apologists say Pales- tine will withdraw from the 'territories' once it has someone to negotiate with, although some Palestinian irredentists say they will never give up one inch of the sacred homeland. In municipal elections, Israelis elect a coalition of Likud-Labour candidates, whom the Palestinians im- mediately replace with Israelis who happen to belong to the PLO. The occupation --- with barely audible protests from Jews, civil libertarians and Israeli sympathisers in the West — continues amidst charges of torture, beatings, destruction of homes, deportations, land confiscation and assas- sinations. After 20 years of enduring Palestinian occupation, Israelis begin to demonstrate and then to riot. They orga- nise protests and strikes. They throw 'What odds are we giving on Pascal's Wager?' stones at Palestinian occupying forces, who shoot and beat them. Palestinian officials blame the foreign press for stirring up the trouble. At this moment, liberal Palesti- nians and their sympathisers in the West begin to look at the future. What options do they see? `Hold tight in the hope that the uprising will wear itself out? . . . Get rid of the territories? Few Palestinians support such a solution, especially in view of the dangers of security that would ensue . . . . Organise a mass emigration of Israeli Jews, mainly to New York? . . . Agree to some sort of autonomy for Israeli Jews in the territories? . . . Seek a solution within the framework of a comprehensive peace settlement to be discussed at an international conference? At the moment, it seems a non-starter.'

The Israelis of today understandably intend to remain strong enough so that neither they nor their children will have to face the prospect of seeing their future discussed in these terms by foreigners Palestinian, Soviet or Western. Yet they must see the injustice inherent in discus- sing their freedom and survival, indeed the freedom and survival of any people, in these terms. If the boot was on the other foot, ighat other objective would patriotic Israelis have than to negotiate through their chosen representatives (not Quislings chosen by Yasser Arafat) and, when the other side refuses to meet their leaders, to fight for their rights?

As the American Secretary of State, George Shultz, puts forward his own plan for peace, what is on offer in the final months of an administration whose con- tributions to peace in the Middle East have been the Marine debacle in Beirut and the Iran arms deals? Noam Chomsky, writing last week in the NeW Statesman, asked: But negotiations with whom, and what kind of compromise? The intended answer is: negotiations excluding the chosen repre- sentatives of the Palestinians,' and a com- promise that will leave Israel in effective control of the resources of the West Bank and much of its territory, while excluding the areas of heavy Arab population so as to avoid the problem of too many Arabs in a Jewish state.

The Palestinian response, as the Israeli would be under similar Circumstances, has been to continue the struggle. The rebel- lion began inauspiciously last December with fighting between Palestinians and Israeli settlers in the occupied territories, which had telling similarities to the Arab revolt of 1936 against the British Mandate and the Zionist immigration it permitted. `It all began incoherently enough,' David Hirst wrote in The Gun and the Olive Branch (Faber, 1977, page 82). 'On 15 April 1936, Arabs held up a number of cars on the Tulkarm-Nablus road. They only robbed the Arabs and Europeans, but two Jewish travellers they shot, killing one and fatally wounding the other. The next night two Arabs living in a but near a Jewish settlement met the same fate.'

The fighting spread and continued for the next three years, until the British army crushed it. In that time, according to official Mandate reports, 3,073 Arabs were killed. The actual figure may have been higher, with 5,032 dead and 14,000 wound- ed by the British authorities and Zionist para-military groups. (See 'Appendix IV: Note on Arab Casualties in the 1936-39 Rebellion' in From Haven to Conquest, Walid Khalidy, editor, Institute of Pales- tine Studies, 1971). Would even Israel's staunchest defenders in the New York Times and elsewhere tolerate nearly 5,000 Palestinians killed over each of the next three years? About whose agony would they choose to write? Marc Ellis, a perceptive American Jew- ish theologian, is one of the few observers whose genuine concern for Israel has led him to consider Israel's victims. There is a difference, he wrote in the Tablet of 27 February, between the Judaism of the Holocaust and that of holding power over another people. 'Today,' • Ellis wrote, `there is a new generation of dwellers in the ghetto — only this time they are on the other side, subjects of Israeli power.' There is a message coming from that ghetto: What we Jews are being told, if we could only listen, is that our theology, Holocaust theology, is no longer adequate to the history we are creating: that our empowerment is overwhelming the Holocaust experience and its critique of injustice; that we are no longer Innocent sufferers but that we have within our fold a powerful, often dangerous, and in regard to the Palestinians, unjust state. We are being told that unless we change our perception of ourselves as we exist today, we will become everything we loathed about our oppressors.

Finally, Ellis posed these disturbing ques- tions: 'Does empowerment which oppres- ses others signal faithfulness to the cries of the victims of the Holocaust? Does empowerment which oppresses symbolise the kind of people we were, the people we would like to become?'

The Palestinians too, along with their leaders, should be asking themselves the same questions. What kind of people do they hope to become? Would their state be another Syria, Iraq (which recently intro- duced a press law making it a death penalty offence to insult the president) or Saudi Arabia? While it is obvious that the PLO has officially accepted UN Resolutions 242 and 338, with their explicit recognitions of Israel, it is not so obvious the PLO would bring a democratic and humane govern- ment to an independent Palestinian state. That is Palestine's problem, not Israel's. The organisation appears to be taking effective control of the rebellion in the West Bank and Gaza, channelling popular discontent into constructive protest, but there is more to leadership than that. David Hirst noted an aspect of the 1936-39 rebellion which bears a striking similarity of today's troubles:

The Palestinian leadership did not plan this revolt any more than it did the riots and massacres of the 1920s. Nevertheless, in order to maintain its own supremacy, it accepted an involvement — though just how much is controversial — which was thrust upon it. The revolt was largely spontaneous in origin. . . .

That revolt began 18 years after the British under Allenby occupied Palestine. This one took 20 years to brew, and the Palestinian leadership has once again had involvement in a popular revolt thrust into its hands. Whether it makes more of this one than its predecessors did of the last, when feudal rivalries overshadowed their opposition to the Zionists, remains to be seen.

There is much to discuss, if ever the chosen representatives of the Israelis and Palestinians get down to the talking. Mean- while, the glass fibre truncheons are on order.

Previous page

Previous page