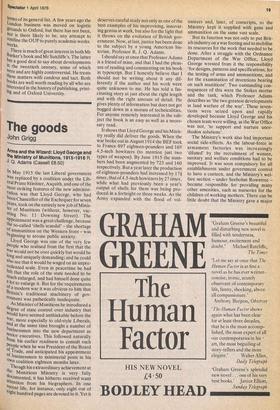

Early Spring books

The presse working

Robert Blake

The Oxford University Press and the Spread of Learning: An Illustrated History Nicholas Barker (Clarendon Press: Oxford University Press £10) The Oxford University Press: an informal History Peter Sutcliffe (Clarendon Press: Oxford University Press £6.75)

These two books commemorate five hundred years of printing in Oxford 14781978. As a Delegate of the OUP who recently assisted in blowing out some of the 501 candles on a gigantic birthday cake in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, I must declare an interest in both of them. Mr Nicholas Barker's is intended partly as a companion to the Quincentenary Exhibition at which the cake made its brief appearance and which will move during the year from New York to Western Ontario, to the Victoria and Albert Museum and to Frankfurt. His book is beautifully produced, admirably printed and copiously illustrated. Mr Sutcliffe's 'informal' history is informal only in the sense that there are no footnotes, because the material on which it is based has never been indexed. It is both scholarly and highly readable. Mr Sutcliffe deals mainly with events since 1860. The first volume of the Harry Carter's History of the Oxford University Press (1975) took the story to 1780, and a second volume will appear in due course. Meanwhile Mr Sutcliffe's is the best account we have of the Press during the last 120 years.

The OUP is a very remarkable institution — a giant publishing organisation, one of the largest in the world, and yet a department (legally) of the University. It is not, however, subsidised by the University and it has to be financially profitable in order to produce the unprofitable learned works which constitute its equivalent of a shareholder's dividend. Its ultimate purpose is the spread of learning and its Delegates (who are roughly equivalent to non-executive Directors of an orthodox publishing firm) are academics appointed by the University.

Although the Press is ancient one cannot credit it with five hundred years of continuous history. The printing activities in Oxford which began in 1478 under the aegis of Theodoric Rood of Cologne ceased abruptly after a few years and after the perpetration of one of the more celebrated misprints in history; the first book, an exposition in Latin of the Apostles' Creed wrongly attributed to St Jerome, was dated 1468, although all the evidence points to this being ten years too early. Printing in Oxford, as almost everywhere else in England, apart from Caxton's press, stopped in 1486. Mr Peter Jay gratified an audience in New York by pointing to the antiquity of a Press which had gone temporarily out of business even before the voyage of Columbus.

There was a brief revival, 1517-20, about which little is known. It was matched by a similarly short-lived episode in Cambridge which, however, unlike Oxford, acquired a Charter to print. It was not exercised till fifty years later and then was at once challenged by the Stationers' Company which claimed a monopoly. In 1586 Oxford along with Cambridge secured special exemption in a decree of the Star Chamber which otherwise prohibited all printing except in London and by freemen of the Stationers' Company. The University's case rested, albeit vaguely, on an already old, if discontinuous tradition of printing during the previous hundred years. This makes a good enough excuse for a quincentenary celebration in 1978. Nevertheless, the whole thing might have lapsed, but for two key figures in the seventeenth century, Archbishop Laud and Dean Fell (the younger), Dean of Christ Church 1660-86.

Laud, who was Chancellor of the University from 1629, secured the very important privilege which Oxford was to enjoy along with Cambridge of disregarding the otherwise exclusive right of the King's Printer to print the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. Dr Fell, remembered by most people for an alleged unlikeability of an indefinable nature, devoted much of his life, after cleaning up Christ Church, to the establishment of a learned press. His great contribution was the 'Fell types' which he imported from Holland and which were far superior to anything in contemporary England. One of the finest books published in modern times (1967) by the Clarendon Press is the account of Fell's activities written by the late Stanley Morison and composed by hand in the original types — probably the last book ever to be thus produced.

Dean Fell also had the idea of housing the printing business in the cellar of the newly built Sheldonian Theatre — about as unsuit.

able a place as could be imagined. There was an unfortunate episode when Fell dis covered that some Fellows of All Souls were clandestinely using the press to print engraved illustrations of Pietro Aretino's sonnets on the various positions suitable for sexual intercourse. 'How Mr Dean tooke to find his presse working at such an imployment I leave you to imagin,' wrote Hum phrey Prideaux to a friend, adding that the Fellows would deserve expulsion 'were they of any other college than All Souls, but there I will allow them to be vertuous that are bawdy only in pictures'.

There was another more serious scandal at the beginning of the eighteenth centurY., The publication of Clarendon's History 01 the Great Rebellion was expected to bring large profits. In fact they were rather disappointing and the result was even less satisfactory because the Vice-Chancellor, William Delaune, President of St John's, embezzled what there was. His successor, William Lancaster, Provost of Queen's, known as 'the Northern Bear', took proceedings against him, which resulted in the sequestration of his presidency in 1709. But time has its revolutions. Six years later he was elected Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity and — even more surprisingly — 1721 he became a Delegate of the Press and of Accounts, presumably on the principle that a poacher makes the best gamekeeper. During the eighteenth century the Press languished until William Blackstone, later the famous author of the Commentaries on the laws of England (published of course bY Oxford), galvanised it into some degree of activity. Blackstone was concerned with the Learned Press. What really mattered, however, in financial terms was the Bible Press, for the evangelical movement produced an immense demand. From 1815 to 1850 the profits were very large, and they have been ever since an important element in the finances of the Press. In one day, 17 May 1881, one million copies of the Revised New Testament were sold. A foreman In Oxford was said to have been offered £2,000 for an advance copy by an American agent.

'In every omnibus, in every railway cornpartment and even while walking along the

public thoroughfare', as Mr Sutcliffe quotes from a contemporary journal, 'people were to be seen reading the New Testament. It was the universal subject of conversation throughout the land.' Alas, the novelty soon wore off and the Revised Version was grossly over-produced with a heavy loss to be set against profits in terms of stock writ' ten down.

The fourth key figure in the history of the Clarendon Press, after Laud, Fell and Blackstone was Bartholomew Price, Secretary to the Delegates from 1868 till 1884 and its first full-time chief executive. Under him the Press developed, as Mr Barker puts it, 'from a somnolent self-contained attachment of a large printing house .t° become the greatest academic publishing house in the world'. The Press had long possessed a London outlet, the Packer farnily from 1678 to 1862, followed by Alexander Macmillan till 1881, and by Henry Frowde till 1913. Until 1906 the London business was solely concerned with sales and promotion and this was true of the Cambridge University Press's London end too. But in that year Oxford made a major departure by abdicating from responsibility for a substantial part of the Oxford list and leaving it to the London publisher. The, result was a large growth in general books IN a non-academic nature in the strict sense of the adjective. In 1896 the New York brand was founded with a similar independence in

terms of its general list. A few years ago the London business was moved on logistic grounds to Oxford, but there has not been, nor is there likely to be, any attempt to confine the OUP to purely academic works. works.

There is much of great interest in both Mr Barker's book and Mr Sutcliffe's. The latter has a good deal to say about developments In the twentieth century, some of which were and are highly controversial. He treats these matters with candour and tact. Both b, ooks are well worth reading by all who are interested in the history of publishing, printlog and of Oxford University.

Previous page

Previous page