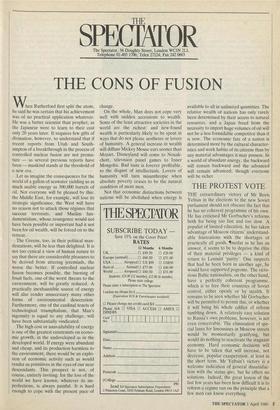

The Spectator, 56 Doughty Street, London WC1N 2LL Telephone 01-405

1706; Telex 27124; Fax 242 0603

THE CONS OF FUSION

When Rutherford first split the atom, he said he was certain that his achievement was of no practical application whatever. He was a better scientist than prophet, as the Japanese were to learn to their cost only 20 years later. It requires few gifts of divination, however, to understand that if recent reports from Utah and South- ampton of a breakthrough in the process of controlled nuclear fusion are not prema- ture — as several previous reports have been — mankind stands at the threshold of a new era.

Let us imagine the consequences for the world of a gallon of seawater yielding us as much usable energy as 300,000 barrels of oil. Not everyone will be pleased by this: the Middle East, for example, will lose its strategic significance, the West will have no reason not to attack those regimes that succour terrorists, and Muslim fun- damentalism, whose resurgence would not have been possible or important had it not been for oil wealth, will be forced on to the retreat.

The Greens, too, in their political man- ifestations, will be less than delighted. It is not too cynical a view of human nature to say that there are considerable pleasures to be derived from uttering jeremiads, the worse the better. If controlled nuclear fusion becomes possible, the burning of fossil fuels, one of the worst threats to the environment, will be greatly reduced. A practically inexhaustible source of energy will also render unnecessary many other forms of environmental desecration. Furthermore, one of the cardinal tenets of technological triumphalism, that Man's ingenuity is equal to any challenge, will have been substantially vindicated.

The high cost or unavailability of energy is one of the greatest constraints on econo- mic growth, in the undeveloped as in the developed world. If energy were abundant and cheap, and its production harmless to the environment, there would be an explo- sion of economic activity such as would render us primitives in the eyes of our near descendants. This prospect is not, of course, entirely inviting: for the loss of the world we have known, whatever its im- perfections, is always painful. It is hard enough to cope with the present pace of

change.

On the whole, Man does not cope very well with sudden accessions to wealth. Some of the least attractive societies in the world are the richest: and new-found wealth is particularly likely to be spent in ways that do not please aesthetes or lovers of humanity. A general increase in wealth will diffuse Mickey Mouse ears sooner than Mozart. Disneyland will come to Nouak- chott, television panel games to Inner Mongolia. Bad taste is forever profitable, to the disgust of intellectuals. Lovers of humanity will turn misanthropic when absolute poverty ceases to be the natural condition of most men.

Not that economic distinctions between nations will be abolished when energy is available to all in unlimited quantities. The relative wealth of nations has only rarely been determined by their access to natural resources, and a Japan freed from the necessity to import huge volumes of oil will not be a less formidable competitor than it is now.. The economic fate of a nation is determined more by the cultural character- istics and work habits of its citizens than by any material advantages it may possess. In a world of abundant energy, the backward will remain backward and the advanced will remain advanced; though everyone will be richer.

Previous page

Previous page