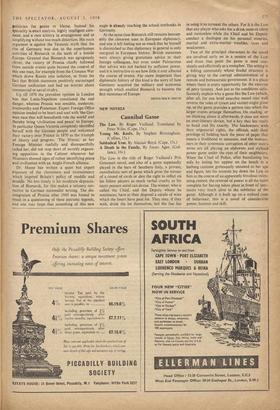

NEW NOVELS

Cannibal Game

Young Mr, Keefe. By Stephen Birmingham. (Collins, 15s.)

The Law is the title of Roger Vailland's Prix Goncourt novel, and also of a game supposedly played in the bars of Southern Italy, a private, cannibalistic sort of game which gives the winner of a round of cards or dice the right to inflict on his fellow players as much verbal cruelty as his nasty peasant mind can devise. The winner, who is called the Chief, and the Deputy whom he nominates, have at their disposal a carafe of wine which the losers have paid for. They may, if they wish, drink the lot themselves, but the fun lies

in using it to torment the others. For it is the Law that any player who asks for a drink must sit silent and motionless while the Chief and his Deputy conduct a duologue on his personal miseries„ marital and extra-marital troubles, vices and weaknesses.

Two of the principal characters in the novel are involved early on in a session of the Law and from that point the game is used con- stantly and effectively as a metaphor. The setting is. a fishing community whose feudal structure is. giving way to the corrupt administration of a remote and bureaucratic government. It is a place where there is every opportunity for the exercise of petty tyranny. And just as the conditions satis- factorily explain why a game like the Law (which, after all, for one brief anarchic round may well reverse the roles of tyrant and victim) might grow up, so the game provides a pattern into which the larger events arrange themselves. On reading, or on thinking about it afterwards, it does not seem an over-literary device, but a key that lies ready to hand and fits exactly. The landowners with their seigneurial rights, the officials with their privilege of holding back the piece of paper that means a livelihood to someone, and the woman- isers in their systematic corruption of other men's wives are all playing an elaborate and stylised power game under the eyes of their neighbours. When the Chief of Police, after humiliating his wife by letting her appear on the beach in a bathing costume grotesquely unsuited to her age and figure, lets his mistress lay down the Law to him in the course of an apparently frivolous swim- ming contest, the, reversal of power is all the more complete for having taken place in front of spec- tators very much alive to the subtleties of the game. Although it is built up on a stylised code of behaviour, this is a novel of considerable power, humour and skill. Young Mr. Keefe, Stephen Birmingham's highly and justly praised first novel, is concerned with a theme popular with young American novelists : the gradual distintegration of the friendships formed in college days, which, when everyone was young, good-looking and rich, promised to last for ever. What Mr. Birmingham is particularly skilful at is catching the mood and the conversation of an occasion; and since he is less sure in his manipulation of the plot what you are left with is the memory of two set pieces. The first is the opening sequence which describes the excursion of three young New Englanders who have settled in California, Blazer and Claire Gates and Jimmy Keefe, on a camping weekend in the mountains, their failure to enjoy themselves as they would have only a few years before, and their hurt bewilderment. This is poignant and exact, and nothing later in the book comes quite so sharply into focus. But nearly as good is the dis- astrous party which the Gates give in their glass- house *flat overlooking San Francisco, which finally forces them to realise that the dear dead college days are beyond recall.

Sabbatical Year, by Alastair Boyd, is a lively entertainment divided into two episodes which, unfortunately, just fail to complement each other to one's complete satisfaction. A young someone in the City, coming into money, decides to throw it all up and write a novel. But he is a man whose intelligence, as a key phrase puts it, outstrips his capacity for action. After being flushed from his rural retreat in England by an unfortunate affair with a literary horsewoman, he has to be saved from just as dangerous a liaison with a Spanish dancer. Written with sympathy and a bland irony, and thoroughly recommended.

A Death in the Family was put together from the manuscript after James Agee's early death,

without alteration or addition save of certain sec- tions which do not fit very neatly into the story, but which, it seems, the editors felt they could hot waste. That is a pity; the prose-poen1 introduc- tion gives a false impression of a novel which turns out to be painstakingly visualised, carefully worked over, sensitive and rather sentimental, but certainly not crafty and verbose.

GEOFFREY NICHOLSON

Previous page

Previous page