A time of Dread

Michael Humfrey

About a year ago, while I was in London on a brief visit, an intense young social porker in Notting Hill told me: 'The West Indian teenagers in London are deliberately being harassed by the police. Some of us struggle for months to build up an atmosphere of trust and then the police come along and destroy it in one night. The situation is getting worse all the time.'

She was very concerned, very sincere. Two years previously her conscience had driven her from a comfortable flat with a view across Wimbledon Common to a single cramped up room in Notting Hill among the immigrant people she cares for. She was convinced that very serious trouble was coming and she thought that the attitude of the police was largely to blame. They had one standard for whites like herself, she said, another for blacks. A former member of the Commission for Racial Equality agreed with her. He spoke sadly of the 'antediluvian attitudes' of many top policemen.

A senior police officer disagreed: 'The police are not colour prejudiced, but they've got a job to do. If the statistics show that in a given area 80 per cent of the muggings are the work of black teenagers, then of course we have to pay particular attention to young blacks in that area. We can't just pretend it's not happening'. He declined to comment on the work of the Council of Churches and the Commission for Racial Equality in immigrant areas, but other policemen are not always so reticent. There is a widespread belief that many of the social workers and other 'do gooders' tend to aggravate a bad situation.

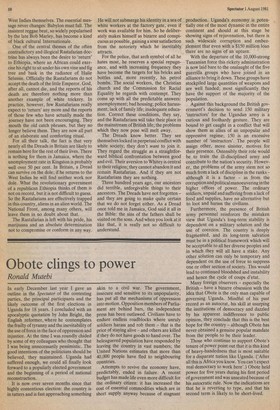

In the 12 months since my visit the worst fears of everyone I spoke to have become part of our national history. Mention Brixton, St Pauls, or Toxteth, and everyone knows immediately what you are talking about. You can see them lounging on the street corners of every British city with a large black population — a group of six or more black teenagers, watching the panda cars go by. Most of them were either born in Jamaica or have Jamaican parents. They are dressed alike: jeans, sunglasses and knitted woollen 'tams' in the Ethiopian colours of red, green and yellow. Their hair is carefully plaited into long 'dreadlocks' and hangs below the level of their shoulders. 'Whitey got to learn,' they say. 'Dem can't keep us down no more. Is black man time now.' They intend to look menacing, and they succeed without effort. They are Rastafarian 'Dreads' and to the police and to many other people in the area they mean trouble.

Although the Rastafarians are still only a comparatively small element within the West Indian community in Britain, they exert an influence on young West Indians out of all proportion to their numbers. They take pride in being different. They are openly contemptuous of their own countrymen who have accepted the white man's values and who have successfully conformed to the rules of British Society. 'Uncle Tom niggers' they call them. Their real hostility, however, is reserved for the white man himself. It is a bitter, unremitting hatred and every now and then it finds expression in a brutal mugging, where the motive is more the infliction of pain than the desire for money, or a brick hurled through the window of a passing police car; or, more recently, and on a larger scale, in the riots of the inner cities.

What exactly do they want, these alienated young men with sullen faces and closed minds? They are not quite sure themselves; but they are all agreed on one point: Whitey owes them something for what he did to their ancestors on the Guinea coast 300 years ago. They have very definite ideas about what took place then. They know all about Sir John Hawkins and his friends, and they can tell you the exact number of slaves who were tossed into the stinking holds of the slave ships like so many bags of dark sugar. They know how many usually died on each crossing of the Middle Passage, and how the sick were simply thrown overboard when the captains thought them unlikely to survive the journey. They have a very clear mental picture of their ancestors at work under the overseer's lash on the West Indian sugar estates. Britain's wealth, they say, was paid for in African sweat and blood. Whitey owes them something for that, and they intend to collect in whatever way they can.

The Dreads' philosophy has been imported from Jamaica, and it has suffered little change on its journey across the Atlantic. Its roots lie deep in Jamaican history and to understand it one needs to know something about that history. Like their brothers and sisters in Haiti, the Africans who were brought to Jamaica never accepted the soul-destroying condition of slavery. The history of that most beautiful of islands is punctuated by bloody revolts against the white colonists. In the 18th century the British garrison, unable to conquer a guerrilla army of runaway slaves, signed a formal peace treaty with them and recognised their free status. One of the most famous guerrilla leaders was a woman, who showed her opinion of the British army by wearing a bracelet of human teeth around her ankle. The teeth all came from the bodies of soldiers ambushed by the black guerrillas.

The abolition of slavery in 1838 did not end the struggle. As late as 1865 a band of peasants — desperate for arable land of their own — murdered a number of Europeans, including the Governor's personal representative. The rebellion was put down with merciless severity and more than 400 blacks were summarily executed and thrown into a single mass grave.

The Rastafarian movement itself dates from the time of Mussolini's invasion of Haile Selassie's kingdom of Ethiopia in 1936. The little African Emperor's struggle to redeem his country stirred a great wave of sympathy in the West Indies, where the invasion was seen as yet another attempt by the white man to enslave the black. Ethiopia, after all, was the cradle of the black race; and to some it soon became apparent that Haile Selassie was the new Messiah, God incarnate. A black God for a black people.

The movement took its title from the Emperor's real name — Ras Tafari. Its ritual centred around the Nia-binghi ceremony, a dance which celebrated the destruction of the white race. The Rastafarians rejected all of what they perceived as white culture; they were, in fact, pioneers of what was later to be called 'negritude'. They interpreted the Bible freely to suit their own doctrine: the white world was Babylon, doomed to perish in blood and fire. The black race were God's chosen people. They grew their hair and adopted a way of life, a dialect and even a manner of walking peculiar to themselves. They sought wisdom and revelation in the constant use of marijuana.

For many years, membership of the movement was confined to the very poor and the illiterate. Then in 1962 Jamaica became an independent nation and, with the encouragement of the new government, a wave of 'black consciousness' swept the island. The leaders of the black revolts of the previous century were declared national heroes and statues were erected to them. The facts about slavery and the slave trade — which the Colonial administration had always done its best to keep out of the schools — were now learnt by every child. The militancy and rhetoric of the Black Power leaders in the United States were widely applauded._ A new pride in everything African emerged and this was strengthened by the 'liberation' of the former African colonies. The Rastafarians were belatedly recognised as the only element in the Jamaican society which, through long years of white oppression, had kept faith with their African heritage. They had been the keepers of the flame.

The Rastafarian 'religion' has taken root in Britain — and spread to nearly every other West Indian island — within the last ten years. The provocative lyrics of the reggae records, which are heard everywhere, provide a powerful bond between the Dreads in this country, the United States and in the West Indies themselves. The essential message never changes: Babylon must fall. The insistent reggae beat, so widely popularised by the late Bob Marley, has become a kind of black cultural Internationale.

One of the central themes of the often contradictory and illogical Rastafarian doctrine has always been the desire to 'return' to Ethiopia, where an African could exercise his right to sit under his own vine and fig tree and bask in the radiance of Haile Selassie. Officially the Rastafarians do not accept the death of the little Emperor. God, after all, cannot die, and the reports of his death are therefore nothing more than another example of white trickery. In practice, however, few Rastafarians really expect to 'return' any more and the reports of those few who have actually made the journey have not been encouraging. They mouth the old catch phrases, but they no longer believe them. They are now all part of an elaborate and comforting ritual.

For all their talk, the fact is that very nearly all the Dreads in Britain are likely to remain here for the rest of their lives. There is nothing for them in Jamaica, where the unemployment rate in Kingston is probably well over 50 per cent. In Britain, a Dread can survive on the dole; if he returns to the West Indies he will find neither work nor dole. What the revolutionary government of a republican Ethiopia thinks of them is not on record, but it is not difficult to guess. So the Rastafarians are effectively trapped in this country, aliens in an alien world. The National Front, among many others, will leave them in no doubt about that.

The Rastafarian is left with his pride, his marijuana and an absolute determination not to compromise or conform in any way. He will not submerge his identity in a sea of white workers at the factory gate, even if work was available for him. So he deliberately makes himself as bizarre and conspicuous as possible, gaining a sour satisfaction from the notoriety which he inevitably attracts.

For the police, that arch symbol of all he hates most, he reserves a special repugnance, and with increasing frequency they have become the targets for his bricks and bottles and, more recently, his petrol bombs. The social workers, the Christian church and the Commission for Racial Equality he regards with contempt. They come up with all the predictable answers: unemployment; bad housing; police harassment; lack of family life; inadequate education. Correct these conditions, they say, and the Rastafarians will take their place in the mainstream of British life; the problems which they now pose will melt away.

The Dreads know better. They see themselves locked in perpetual conflict with white society; they don't want to join it. They regard the struggle as a straightforward biblical confrontation between good and evil. Their aversion to Whitey is central to their religion; they cannot abandon it and remain Rastafarian. And if they are not Rastafarians they are nothing.

Three hundred years ago, our ancestors did terrible, unforgivable things to their ancestors. The Dreads have not forgotten — and they are going to make quite certain that we do not forget either. As a Dread once told me in Jamaica, God said it all in the Bible: the sins of the fathers shall be visited on the sons. And when you look at it like that, it is really not so difficult to understand.

Previous page

Previous page