RESHUFFLE DAY WITH GORDON

As officials came and went, and ministers rose and fell, the

Chancellor talked to Petronella Wyatt IT WAS five o' clock on Monday afternoon and the Prime Minister was in the middle of announcing the reshuffle. The media had already seized upon the promotion of numerous `Blairites' as a significant setback to the Gordon Brown's ambitions.

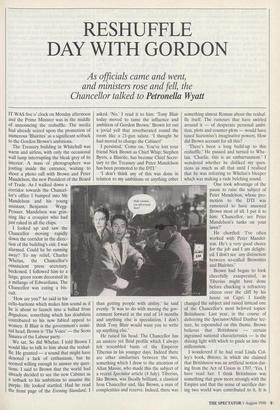

I looked up and saw the Chancellor moving rapidly down the corridor in the direc- tion of the building's exit. I was alarmed. Could he be running away? To my relief, Charles Whelan, the Chancellor's omniscient press secretary, beckoned. I followed him to a large, green room decorated in a mélange of Edwardiana. The Chancellor was eating a bis- cuit.

'How are you?' he said in his cello-baritone which makes him sound as if he is about to launch into a ballad from Brigadoon, something which has doubtless Contributed to his now fabled appeal to women. If Blair is the government's nomi- nal head, Brown is 'The Voice' — the Scots Sinatra of the Labour party.

We sat. So did Whelan. I told Brown I would like to talk to him about the reshuf- fle. He grunted — a sound that might have denoted a lack of enthusiasm, but he seemed willing enough to answer my ques- tions. I said to Brown that the world had already decided to see the new Cabinet as a setback to his ambitions to assume the Purple. He looked startled. Had he read the front page of the Evening Standard, I asked. 'No.' I read it to him: 'Tony Blair today moved to tame the influence and ambition of Gordon Brown.' Brown let out a jovial yell that reverberated round the room like a 21-gun salute. 'I thought he had moved to change the Cabinet!'

I persisted, 'Come on. You've lost your friend Nick Brown as Chief Whip; Stephen Byers, a Blairite, has become Chief Secre- tary to the Treasury and Peter Mandelson has been promoted to the DTI.'

'I don't think any of this was done in relation to my ambitions or anything other than getting people with ability,' he said evenly. 'It was to do with moving the gov- ernment forward at the end of 14 months and anything else is speculation. I don't think Tony Blair would want you to write up anything else.'

He raised his head. The Chancellor has an austere yet fluid profile which I always felt resembled busts of the Emperor Tiberius in his younger days. Indeed there are other similarities between the two, something which I drew to the attention of Allan Massie, who made this the subject of a recent Spectator article (4 July). Tiberius, like Brown, was fiscally brilliant, a classical Iron Chancellor and, like Brown, a man of complexities and reserve. Indeed, there was something almost Roman about the reshuf- fle itself. The rumours that have swirled around it — of desperate personal ambi- tion, plots and counter-plots — would have taxed Suetonius's imaginative powers. How did Brown account for all this?

'There's been a long build-up to this reshuffle.' He paused and turned to Whe- lan. 'Charlie, this is an embarrasment.' I wondered whether he disliked my ques- tions as much as all that until I realised that he was referring to Whelan's bleeper which was making a rude belching sound.

One took advantage of the pause to raise the subject of Peter Mandelson, whose pro- motion to the DTI was rumoured to have annoyed Brown most of all. I put it to him: 'Chancellor, are Peter Mandelson's tanks on your lawn?'

He chortled: 'I've often worked with Peter Mandel- son. He's a very good choice for the job and I am delight- ed. I don't see any distinction between so-called Brownites and Blairites.'

Brown had begun to look cheerfully exasperated, as Tiberius might have done before chucking a refractory citizen over the cliff by his house on Capri. I hastily changed the subject and raised instead one of the Chancellor's most beloved topics: Britishness. Last year, in the course of delivering the Spectator/ Allied Dunbar lec- ture, he expounded on this theme. Brown believes that Britishness — certain ingrained national characteristics — is the shining light with which to guide us into the millennium.

I wondererd if he had read Linda Col- ley's book, Britons, in which she claimed that Britishness was an artificial notion dat- ing from the Act of Union in 1707. 'Yes, I have read her. I think Britishness was something that grew more strongly with the Empire and that the sense of sacrifice dur- ing two world wars contributed to it. It is about having a strong civic patriotism. We can find in our history qualities — creativi- ty, adaptability, traditions of fair play, self- improvement — that enable us to be stronger as a country.'

I was surprised to find a Labour politi- cian finding something good to say about the Empire, given the bad press it has received at the hands of left-wing histori- ans. Was Brown an imperialist?

'I think the history of empire is fascinat- ing. It gave Scots, English, Welsh, Irish an opportunity to serve in different parts, to travel the world.'

'You make it sound like a P&O cruise.' 'It was very liberating for all these peo- ple.'

'Was it liberating for the peoples they occupied?'

'Obviously there were different respons- es. But if you take 1947-97, from India to Hong Kong, it's true to say the exit from empire was done in a way that was sensitive to peoples' cultures.'

How did he think Britishness was rele- vant today?

'The old civic patriotism has become, should become, what I'd call a mature patriotism.'

'What's an immature patriotism?'

'To be inward-looking and anti-Euro- pean.'

So people who had doubts about a single currency weren't patriotic, I asked?

Brown's fine fingers fluttered agitatedly, like birds. 'I didn't say that. But I object to those who say that because you are pre- pared to consider a modern relationship with Europe you are unpatriotic. They shouldn't accuse us.'

One remarked that his view of British- ness was selective. Many of our great statesmen had been wary on principle of engaging in 'foreign entanglements'.

'Up to a point. The idea of splendid iso- lation has only commended itself for very short periods of time.'

Brown is a Scot. Was there a conflict between his Britishness and his Scottish- ness? 'Most people who come from Scot- land feel Scottish and British. I don't think it's necessarily a conflict. I support England in football — unless they are playing Scot- land.'

This brought us on to devolution. Things appear to be running away from Labour in Scotland. If the government ever had to face the Gotterdammerung of an indepen- dent nation what would happen to Brown, who has a Scottish seat? Would he be con- tent to sit in a Scottish parliament or would he look for a seat in England?

'That's a hypothetical question.' His voice rumbled. won't answer that. But I believe the British constitution as it is is good for Britain and good for Scotland.'

Brown is one of the few people in the government who would seem to believe in anything. He is also one of the few people in the government who seem to think on more than a superficial level. He began his career as a university lecturer. Would he describe himself as an intellectual?

He appeared shocked and embarrassed. 'I don't think that's the word I would use. I think in politics it's important to have a set of ideas, principles, so people know where you stand.'

Suddenly the door was thrown open and one of the young Brownies appeared. It was the Chancellor's turn in the reshuffle. 'I'm very sorry,' the aide said, 'but the PM wants to see you now. I think it's OK, though. Boom, boom!' Brown turned to me, rolling liquid eyes. 'It's just one of those days. Can you come back tomorrow morning? We can continue then.' He addressed Whelan: 'Fix it, Charlie.'

The following morning I was back at the Treasury. The Chancellor was in a meeting, so I drank a cup of coffee and read the papers which, like yesterday's Evening Stan- dard, portrayed the reshuffle as an attack on Brown. Presently the Chancellor put his head around the door. He made a futile gesture at the headlines. I thought of some of Brown's predecessors and their vicissi- tudes and asked him which past chancellors he most admired. He could not seem to think of any. 'I don't know. It's really diffi- cult. I respect what some of my Labour col- leagues have tried to achieve but as someone who has studied history, I would prefer to go back further and look at what Lloyd George did, and Gladstone.'

I said that Gladstone had a reputation for being arrogant. Brown, it is rumoured, won't suffer fools. He seems uncomfortable with displays of emotion, with the matey- ness that is a prerequisite of modern poli- tics. This is a characteristic which may have contributed to his fabled decision to stand aside for Tony Blair. Again one could see that Tiberian austerity, whereas Blair has the crafty openness of the Emperor Augus- tus who could even bring himself to weep in public.

'You have certain Roman qualities,' I told Brown, who giggled. 'Blair has certain qualities, but he has ascended to the purple and you have not. What qualities does Blair have which you lack? I believe that you said recently that you "hated touchy- feeliness".'

'Actually, I didn't use that phrase, but I said something similar.'

Did he feel that had held him back as a politician? He pondered. 'I don't know. I hope at the end of the day people judge you on what sort of job you do as opposed to what you say about how you are doing it. But I hope I don't come across as stiff."

Did he think society had become too intrusive and informal? Lord Stoddart of Swindon complained last week that NHS staff addressed him by his christian name. Wasn't the Chancellor embarrassed when people he'd never met called him 'Gor- don'? To my surprise he said, 'Actually I'd prefer to be called Gordon. We are just men and women, after all.'

'Like Adam and Eve, I suppose? But have you no respect for your office?'

'I'm no different from the man on the street.'

'Then what on earth are you doing as Chancellor, er, Gordon, if you're no differ- ent from the man on the street?'

'Well, I just happen to be Chancellor. A lot of it is luck.'

Our discussion led us to Brown's person- al life. For a while now he has been seeing the lissome PR Sarah Macaulay, something about which he is loth to talk. Did he think it ridiculous that in an allegedly sophisticat- ed world the press became so exercised over a politician's marital status?

Brown may have recently decided to change tack and employ a more open — a more Augustan — approach, for he said, 'The idea that people should not know what you do is ridiculous. You have to con- duct yourself with more discretion but you have to be realistic. People ought to be as open as possible. I don't complain about it.'

'But you must have minded when Sue Lawley raised rumours about your sexuality on Desert Island Discs?'

'No, I didn't mind. It was said that I com- plained, but that's not true.'

Wouldn't the matter be resolved, one suggested, if he just bit the bullet and mar- ried? The Chancellor shook his head. 'You have to do what is right. It's not better to be six times married than to be single. You have to do what's right.'

Brown is said to be pitifully undomesti- cated, to the extent of not being able to tie his shoelaces, let alone remembering where his shoes came from. He refused, though, to recognise this picture of himself.

'I don't think it's true.'

Did he ever cook? 'Yes I do.'

What? 'French, Italian, English.'

Where did he get his shoes? 'Church's,' he said, quick as a flash.

I had the impression Brown uses his much vaunted vagueness as a stalking horse under the cover of which he disarms opponents. Into the creation of Gordon Brown has gone a great deal of work. He is said to telephone his secretaries at six in the morning. 'Why are you such a worka- holic?' I asked. 'Are you running away from something?'

'I'm not a workaholic, but work is very important to me. It is one of those great British qualities. When that was destroyed something very precious was taken away from people — the fundamental ability to express yourself.'

Was a lavatory cleaner exercising his fun- damental ability to express himself? Had Brown read Bertrand Russell's In Praise of Idleness which argues that leisure is infinitely preferable to some forms of menial work?

'Yes, that kind of work is not very inter- esting. We've just got to help people to ful- ful their potential.'

Brown insisted that he set aside time to develop the Healeyesque personal hinter- land. 'Aside from sport I love music, partic- ularly Bach. I used to play the piano and the cello, though unfortunately I wasn't good enough to make a career out of it.'

His father was a Church of Scotland min- ister. Brown is not a regular churchgoer but admits to praying. 'Well, we all do in our different ways,' he observed. We talk about Calvinism which frightened Brown because of its unforgiving predestinarian theology. He said, 'It's a terrible thing to say some- one is predestined to be damned.'

'Do you :believe in predestination, Gor- don?' I enquired. 'Do you think you are predestined to become prime minister?'

He exploded. 'I don't think it will depend on anything like that.'

It might depend, however, on a continu- ing reputation for fiscal prudence. Was Brown concerned that his recent announcement of £57 billion expenditure proposals would lose him the tag of 'Iron Chancellor'? 'It's only because we have been tough in other areas that we can do it,' he said defensively. 'We are selling off a number of assets, we're squeezing other budgets, we're raising efficiency targets.'

'But surely one of the lessons of the post- war period is that the NHS is a behemoth that eats money. Are you like the Bourbons who learnt nothing and forgot nothing?'

'I agree with you. That's why we have developed the toughest efficiency targets.'

I asked Brown if it will eventually lead to tax rises. 'Our expenditure plans are cov- ered by tax revenues. We can be both pru- dent and spend. I don't think these spending proposals will frighten Middle England. They are based on very cautious calculations.'

Brown jumped to his feet. 'I'm sorry, but I'm off to see the Archbishop of Canter- bury now.'

'What about?' I wanted to know. 'Pre- destination?'

'No, I'm going to talk to the bishops about international debt.' He looked grun- tled — the way you and I would look if we had said we were going off to see an excit- ing new play or opera. Among the politi- cians I have met, Gordon Brown is the one whose work is most a part of him, an organic thing that is impossible to separate from his personality. He has that classical sense of public duty — which brings us back to the Romans. As I left the Treasury, I remembered that when Tiberius finally made it to the purple he enjoyed one of the longest reigns of any emperor.

Previous page

Previous page