ARTS

Rejecting the idea of continuity

Andrew Wordsworth questions whether Siena is the right place for a modern sculpture exhibition The people of Siena are busy preparing for the Palio, the horse-race that has been held twice yearly in the city ever since the 15th century. The race, in which men repre- senting the different contradas (or districts) ride bareback round the main piazza, simul- taneously unites and divides the Sienese. Rivalry between the contradas is intense, and large sums of money are spent trying to fix the result in advance. But the Patio is also a pretext for celebrating the city's par- ticular sense of identity and history — so there are flag-throwing ceremonies, proces- sions in mediaeval costume, and banquets in the streets and piazzas.

This year, residents of 'The Tortoise' contrada are up in arms, because a huge pear-shaped stone sculpture has been installed in the piazza where they normally have their banquet. Seven-metres high and weighing 82 tons, Digitus-Rational Being' is the work of Tony Cragg, whose one-man exhibition here will last all summer. Nick- named 'The Pear of Discord' by the local press on account of the uproar it has pro- voked, it has become a symbol of the entire exhibition, and the target for popular dis- content. Taxpayers object to the comune (or city council) spending 250 million lire (about £90,000) on sponsoring works of art which they don't appreciate or understand, and which jar with the mediaeval atmo- sphere of the city.

It was precisely in order to counter the profound conservatism of the Sienese, and to bring the city a bit more up to date, that a programme of contemporary art was launched by the comune. Cragg was invited to open the season: his exhibition includes work brought from Germany, where he lives, but is centred on five large pieces cre- ated specially for the occasion, using local materials — stone, glass and terracotta — and with the help of Tuscan craftsmen.

Cragg's use of the raw material has been characteristically idiosyncratic. Travertine is an easy stone to carve, but Cragg is not interested in doing anything so obvious or traditional. His sculptures are composed of horizontal layers of stone, glued or fixed together, a device designed to recreate the effect of rock strata. In this way the fin- ished work of art reminds us of its natural origin, bypassing or transcending the hard work involved in creating the piece — which in any case is carried out by the local stone-masons, and not by the artist himself. His contribution is intellectual rather than manual: he controls operations from a dis- tance, planning and modifying shapes with- out entering into direct contact with the material.

Cragg's refusal to create images out of massive blocks of stone distances him from the creative principles of the Renaissance — to which cities like Siena and Florence are monuments. For him, carving as an aes- thetic discipline belongs to the Newtonian universe of solid and definite bodies; nowa- days our understanding of mass and matter is radically different, and sculptural tech- niques must adapt to this new knowledge. This attitude is better understood if we remember that Cragg's background is sci- entific and not artistic. His initial training was as a biochemist, and in conversation he makes free use of scientific vocabulary: 'the present ... could be defined as a sum of chemical changes taking place in our body', or, 'the landscapes of the 20th century are very much different molecularly and spa- tially than in previous centuries'. His work likewise owes a lot to the years spent in the laboratory: he assembles his sculptures out of a number of similar elements very much as a scientist puts together a molecular model, endeavouring to give three- Paesaggio Senese — Eroded Landscape' dimensional form to a particular concept.

The Italian press have called Cragg the natural heir to Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, but the claim is misplaced, as Cragg would be the first to point out. If we compare this exhibition with Henry Moore's 1972 retrospective in Florence, the differences are clear. Moore placed himself in the great tradition of European sculp- ture, and, while modern, his work was per- fectly at home in the city of Donatello and Michelangelo — to whom he constantly referred. Siena, likewise, contains sculp- tural masterpieces, in particular Giovanni Pisano's figures for the façade of the Duomo, but for Cragg any sort of dialogue with this heritage is out of the question, as his sense of modernity rejects the idea of continuity, of a living tradition. He plays down the importance of memory (whether personal or collective) in art, preferring to generate meaning in his work through metaphor, which allows one form to sug- gest another in a sideways movement which does not involve past or future.

At times the propositions that Cragg offers are so tendentious and confused as to invite disbelief. In the Palazzo Pubblico we come across a pile of terracotta dishes with the inexplicable title 'Shiva', which at first glance seems to be a still-life composi- tion. Not at all, says Cragg: 'Because the terracotta sculpture is formed by vessels, it is metaphorically related to organs, to beings, so I obviously feel something figu- rative in it. But it has been made in a way that gives it a further degree of abstraction that makes it relate more to atmosphere, which again has more to do with land- scape.' For me, 'Shiva' remained a pile of dishes and nothing more.

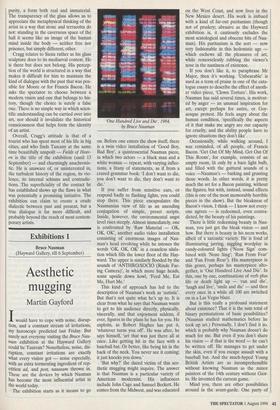

We can see a similar thought-process at work in a sculpture composed of rejects from a glass factory which, together with a large pile of demijohns, make up not a still- life but a landscape ('Paesaggio Senese — Eroded Landscape'). Here, however, the intellectual juggling comes off, thanks to the care and inventiveness with which the work is assembled. All the glass in this elab- orate sculpture has been sand-blasted, so that it holds the light instead of reflecting it. Three-metres high and seven-metres long, the 'landscape' is situated in the main hall of a mediaeval hospital. The filtered light from a huge window gives the sculpture a weightless, luminous quality, while the white-grey of the sand-blasted surfaces matches the colours of the walls and floor — whose hexagonal patterning of black and white tiles harmonises perfectly with the honeycomb arrangement of the demijohns. The sculpture works both in its own right and in context. It is an image of Platonic purity, a form both real and immaterial. The transparency of the glass allows us to appreciate the metaphysical thinking of the artist in a way that stone and terracotta do not: standing in the cavernous space of the hall it seems like an image of the human mind inside the body — neither free nor prisoner, but simply different, other.

Cragg relates to Siena rather as his glass sculpture does to its mediaeval context. He is there but does not belong. His percep- tion of the world is structured in a way that makes it difficult for him to maintain the kind of dialogue with the past that was pos- sible for Moore or for Francis Bacon. He asks the spectator to choose between a modern vision and one that belongs to his- tory, though the choice is surely a false one. There is no simple way in which scien- tific understanding can be carried over into art, nor should it invalidate the historical consciousness that helps form the identity of an artist.

Overall, Cragg's attitude is that of a tourist who has spent most of his life in big cities, and who finds Tuscany at the same time beautifully unspoilt — Fields of Heav- en is the title of the exhibition (until 13 September) — and charmingly anachronis- tic. He is unaware of, or uninterested in, the turbulent history of the region, its vio- lence, its internal schisms and contradic- tions. The superficiality of the contact he has established shows up the flaws in what was potentially a promising initiative. The exhibition can claim to create a crude dialectic between past and present, but a true dialogue is far more difficult, and probably beyond the reach of most contem- porary artists.

Previous page

Previous page