Exhibitions 1

Bruce Nauman (Hayward Gallery, till 6 September)

Aesthetic mugging

Martin Gayford

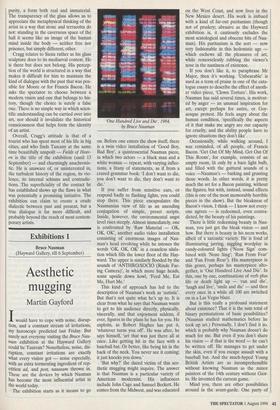

Iwould have to cope with noise, disrup- tion, and a constant stream of irritations, my horoscope predicted last Friday. But surely not everyone visiting the Bruce Nau- man exhibition at the Hayward Gallery could be Taurean? Nonetheless, noise, dis- ruption, constant irritations are exactly what every visitor got — noise especially, With an extra tormenting ingredient of rep- etition ad, and post, nauseam thrown in. These are the devices by which Nauman has become the most influential artist in the world today. The exhibition starts as it means to go 'One Hundred Live and Die', 1984, by Bruce Nauman on. Before one enters the show itself, there is a twin video installation of 'Good Boy, Bad Boy', a quintessential Nauman piece, in which two actors — a black man and a white woman — repeat, with varying inflec- tions, a litany of statements, as if from a crazed grammar book: 'I don't want to die, you don't want to die, they don't want to die.'

If you suffer from sensitive ears, or respond badly to flashing lights, you could stop there. This piece encapsulates the Naumanian view of life as an unending conjugation of simple, preset scripts. Inside, however, the environmental angst level rises steeply. Almost immediately, one is confronted by 'Raw Material — OK, OK, OK', another audio video installation consisting of enormous images of Nau- man's head revolving while he intones the words 'OK, OK, OK' in a ceaseless ulula- tion which fills the lower floor of the Hay- ward. The upper is similarly flooded by the sounds of 'ANTHRO/SOCIO (Rinde Fac- ing Camera)', in which more huge heads, some upside down howl, 'Feed Me, Eat Me, Hurt Me.'

This kind of approach has led to the description of Nauman's work as 'autistic'. But that's not quite what he's up to. It is clear from what he says that Nauman wants to get to his audience directly, physically, viscerally, and that enjoyment seldom, if ever, figures in the plans he has for you. He exploits, as Robert Hughes has put it, 'whatever turns you off'. He was after, he says himself, 'art that was just there all at once. Like getting hit in the face with a baseball bat. Or better, like being hit in the back of the neck. You never see it coming; it just knocks you down.'

'But why?' the dazed victim of this aes- thetic mugging might inquire. The answer is that Nauman is a particular variety of American modernist. His influences include John Cage and Samuel Beckett. He comes from the Midwest, and was educated on the West Coast, and now lives in the New Mexico desert. His work is imbued with a kind of far-out puritanism (though not of prudery; abrasive as the Hayward exhibition is, it cautiously excludes the most scatological and obscene bits of Nau- man). His puritanism is the sort — now very fashionable in this hedonistic age — which eschews all the pleasures of art, while remorselessly rubbing the viewer's nose in the nastiness of existence.

If you don't like it, to paraphrase Mr Major, then it's working. 'Unbearable' is used as a term of praise in one of the cata- logue essays to describe the effect of anoth- er video piece, 'Clown Torture'. His work, Nauman has said several times, is motivat- ed by anger — an unusual inspiration for art, except perhaps for satire, or Goy- aesque protest. He feels angry about the human condition, 'specifically the aspects of it that make me angry are our capacity for cruelty, and the ability people have to ignore situations they don't like'.

Occasionally, while walking around, I was reminded, of all people, of Francis Bacon. 'Get Out Of My Mind, Get Out Of This Room', for example, consists of an empty room, lit only by a bare light bulb, and filled with the guttural sounds of a voice —Nauman's — barking and grunting those words. In other words, it is pretty much the set for a Bacon painting, without the figures, but with, instead, sound effects (this is one of the most memorably horrible pieces in the show). But the bleakness of Bacon's vision, I think — I know not every- one agrees — is redeemed, even contra- dicted, by the beauty of his paintings.

There is little redeeming beauty in Nau- man, you just get the bleak vision — and how. But there is beauty in his neon works, albeit of a sarcastic variety. He is fond of illuminating jarring, niggling wordplay in candy-coloured lights (Neon Sign' com- bined with 'None Sing'; 'Run From Fear' and 'Fun From Rear'). His masterpiece in this genre, perhaps his masterpiece alto- gether, is 'One Hundred Live And Die'. In this, one by one, combinations of verb plus life or death light up — 'run and die', 'laugh and live', 'smile and die' — and then every once in a while all 100 are switched on in a Las Vegas blaze.

But is this really a profound statement about existence? That it is the sum total of binary permutations of basic possibilities? (Nauman studied mathematics before he took up art.) Personally, I don't find it so, which is probably why Nauman doesn't do much for me. But even if you don't share his vision — if that is the word — he can't be written off. He manages to get under the skin, even if you escape assault with a baseball bat. And the much-hyped Young British Artists are as incomprehensible without knowing Nauman as the minor painters of the 14th century without Giot- to. He invented the current game.

Mind you, there are other possibilities around in the avant-garde. One party of younger artists, while sticking to the same media as Nauman, far from attempting to drive the viewer up the wall, produce art that's almost as entertaining as actual entertainment. Matthew Barney, for instance, billed as the 'American Damien Hirst', has produced a series of art films edging closer and closer to art cinema. The latest, screened here earlier in the year, featured Hollywood standard-photography, sets, costumes, a soundtrack, and an appearance by Ursula Andress. If the plot and symbolism had been a smidgen less opaque, it would have stopped being art altogether and become a movie.

Even more eye-popping is 'Nirvana', a video included in the exhibition by the Japanese artist Mariko Mori currently at the Serpentine (until 9 August). The other work in the show, colour photographs, hologram-like images and videos, is fairly dull. But 'Nirvana' is sensational. Mori her- self, with glowing eyes and dressed in a translucent kimono seems to float off the screen and into the room. Luminous petals, a tear-shaped crystal, and little plastic Bud- dha-like things appear, fly past your head (or they do if you're wearing the special glasses provided). These are special effects Disney would die for.

What does it all mean? Well, it's sup- posed to be to do with the commercialisa- tion of Japanese culture or kitsch and transcendence. But frankly, I think that's just an excuse to allow the puritans of the avant-garde to enjoy watching oriental Teletubbies whizz past their ears — just as the symbolism of the last fin de siècle was largely a pretext for a wallow in lurid imagery. But entertaining it is. Take the children and bring pop-corn.

Previous page

Previous page