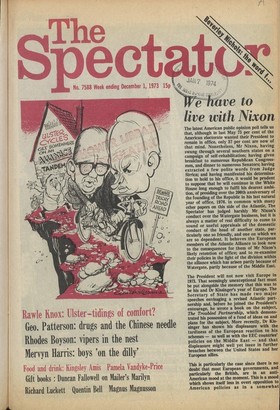

W e have to

live with Nixon

The latest American public opinion poll tells us that, although in last May 75 per cent of the American electorate wanted their President to remain in office, only 37 per cent are now of that mind. Nonetheless, Mr Nixon, having swung through several southern states on a campaign of self-rehabilitation; having given breakfast to numerous Republican Congressmen, and dinner to numerous Senators; having extracted a few polite words from Judge Sirrica; and having manifested his determination to hold to his office, it would be prudent to suppose that he will continue in the White House long enough to fulfil his dearest ambition, of presiding over the 200th anniversary of the founding of the Republic in his last natural year of office, 1976. in common with many other papers on this side of the Atlantic, The Spectator has judged harshly Mr Nixon's conduct over the Watergate business, but it is always a matter of real difficulty to come to sound or useful appraisals of the domestic conduct of the head of another state, particularly one so friendly, and one on which we are so dependent. It behoves the European members of the Atlantic Alliance to look now to the consequences for them of Mr Nixon's likely retention of office; and to re-examine their policies in the light of the division within the alliance which has arisen partly because of Watergate, partly because of the Middle East.

The President will not now visit Europe in 1973. That seemingly unexceptional fact must be put alongside the memory that this was to be his and Dr Kissinger's year of Europe. The Secretary of State has made two major speeches envisaging a revised Atlantic partnership and, before he joined the President's entourage, he wrote a book on the subject, The Troubled Partnership, which demonstrated his possession of a fund of ideas on and plans for the subject. More recently, Dr Kissinger has shown his displeasure with the tardiness of the European reaction to his schemes — as well as with the EEC countries' policies on the Middle East — and that displeasure might well yet issue in further breaches between the United States and her European allies.

This is particularly the case since there is no doubt that most European governments, and particularly the British, are in an antiAmerican mood at the moment. This is a mood which shows itself less in overt opposition to American policies as in a somewhat disgruntled posture towards American diplomacy. Mr Heath, for example, has pointed to the fact that there has never been an agreed Euro-American policy on the Middle East; and, further, that the Americans — and here President Pompidou most whole-heartedly agrees with him — must not expect always to get what they want. In themselves, these are healthy attitudes: there has been far too much submission to the United States since Suez. But there are dangers.

The first danger lies in the possibility that President Nixon — who has, since assuming office, heroically resisted very powerful Congressional pressures drastically to reduce his troop levels in Europe — will now decide that the Europeans no longer deserve military sustenance in the degree to which they have up to now enjoyed it. The second danger lies in the possibility of a rift between Americans and Europeans at either of the two vital series of talks with the Soviet Union and her allies — the Mutual and Balanced Force Reduction negotiations, and the discussion on a European security treaty. The third danger lies in the fact that the current breach has brought measurably nearer the possibility of something which has been in the air for some time — a trade war between the United States and the Common Market. All these dangers and possibilities must be given deep consideration.

This is not to say, however, that the Europeans should retreat again behind the skirts of their American nanny. But if a diplomatic path divergent from that adopted in Washington is to be taken for any distance, then the European powers must look to the consequences of an independent policy. Principal among these would be the necessity for them to spend a great deal more than they do now on defence, while at the same time taking steps to secure the strategic unification of their forces. Defence spending is peculiarly unpalatable to the spoiled and protected peoples of Western Europe, but it must nonetheless be inceased. At the same time pique and stubborness must not be allowed to conceal the essential similarity of interest between ourselves and the Americans: that, too, must be fostered with the greatest tact. All in all, however desirable an independent policy, if only one independent on some issues, it must be realised that every change of course involves paying a price, and involves, too, a great deal of patience, if what was useful in the previous policy is to be maintained. We are not facing an easy period in Atlantic relations.

Previous page

Previous page