FAREWELL TO THE CHIEF?

Charles Haughey is the chieftain of the how he has inspired such loyalty

IN DEMOCRACIES, electorates get the leaders they deserve. The Irish got Charles J. Haughey. The greatest political com- mentator of my lifetime, the late Peter (T.E.) Utley, was both an Englishman and a Unionist. Notwithstanding, he got along personally very well with Irishmen from the Republic, and his analysis of the differ- ence between Fianna Fail Taoiseach, Charles J. Haughey, and sometime Fine Gael Taoiseach, Garret Fitzgerald, was spot on. When he would visit Dublin, Peter would meet Charlie in the Dail, they would have a couple of excellent glasses of malt, and then go around to the Shel- bourne Hotel and enjoy a long and hilari- ous lunch. 'Absolute rascal,' Peter would say, of Haughey. 'Marvellous company. Great talk. As shrewd as a fox.' When Peter would meet Dr Fitzgerald, on the other hand, 'Garret the Good' would bend his ear with statistics and earnest political jargon all afternoon. 'A man of absolute integrity,' said Peter. 'Complete fathead.' The moral of this story is that Peter Utley, unlike so many Englishmen, understood Ireland, and the truth that, most of the time, the Irish would sooner be led by a knave than a fool.

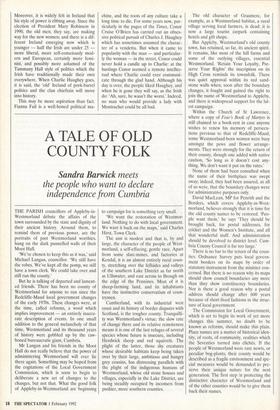

Perhaps, now, but not for much longer, since it is generally agreed that Charlie `Houdinr Haughey, the 65-year-old Taoiseach of the Irish Republic, is not long for this world, politically speaking. He has survived several attempts to unseat him in a manner that would make Machiavelli blush, but even his supporters recognise that the game is up.

Haughey is the subject of much obloquy, a great deal of it deserved. Nobody has ever quite tracked down how he acquired such wealth (a Georgian mansion. in 200 acres, a private island spelt Innishvichillane — and sometimes pro- nounced, out of perversity, Inishfuckalawn — horses, stables, boats).

He has some dodgy friends and cronies who have somehow made fortunes, too. His role in the Arms Trial of 1970 — a gun-running exercise to the North of Ire- land — has never been satisfactorily cleared up. He is a family man in that his children have all prospered magnificently

(his son became Lord Mayor of Dublin at a remarkably young age), and yet there have always been persistent rumours about Charlie and the ladies. He has been known to drink more than is good for him. His administration has tapped the tele- phones of journalists who wrote too criti- cally. And his undemocratic ways within his party have had the government public relations boss, P.J. O'Mara, proclaiming lino Duce! Una voce!' to recalcitrant

party-fodder. The Taoiseach's profile is, to say the least, a blemished one.

And yet, at least among older voters in Ireland, Charlie's apparent weaknesses have often been seen as strengths. My mother, for example, admired Mr Haughey for enriching himself and doing well by his family and friends. Indeed, she refused to vote for Garret Fitzgerald because he had lived in the same modest suburban house all his life. 'If he was any good, he'd have done better for himself.' The Arms Trial accusations may have shocked those who uphold the rule of law, but they probably did Haughey no harm among grass-roots nationalists who, especially in 1970, felt that the Catholics in the North should be defended. His reputation with the ladies never hurt him either: the Irish disapprove of divorce, principally on the grounds that the world's worst sin is splitting up proper- ty, land being sacred among the agricultur- al majority. But if there is no provision for divorce, it is tacitly recognised that blind eyes must occasionally be turned to a man's — particularly a man's — peccadilloes. And the alleged Madame de Pompadour in question, here, is a lady of tremendous flair and style, a grandmother hitting 50, who cuts a glamorous figure around town. ('How does she go on looking so young?' I asked a Dublin friend. 'She only drinks Montrachet,' replied the intimate.) Even a bishop would have to admire such a woman, and many a bishop does. The maitresse en titre story has, true or false, widely enhanced the Taoiseach's reputa- tion, and his wife has sensibly learned to rise above it. And he has a wider reputa- tion, anyway, for being nice to women of all ages. I must have heard dozens of versions of how he helped a dear old lady to get to daily Mass by re-routing the public bus ser- vice nearer to her little cottage.

And if a man enjoys a drop, what of it? Such men are celebrated in song and story in Ireland:

For rambling, for roving, for football or courting, Or drinking black porter as fast as you fill:

In all your days' roving, you'll find none so jovial,

As the Muskerry sportsman of Bould Thady Quill.

Sport, courting, and drinking are, in folk mythology, proper activities for an Irish- man.

Outside commentators who visit Ireland often remark that it is a classless society, fundamentally. In a way, that is true: what Ireland has instead of a class system is a clan system. Loyalty to clan and tribe is what counts. Jobs, favours, planning per- mission in awkward places, inside knowl- edge of building deals, control of state-sponsored bodies are done through the influence of the clan. Fianna Fail and Fine Gael are not so much political parties as contemporary versions of powerful clans, and as in all clan traditions particular families dominate. (Even Garret the Good's form is dynastic: his father was a politician, his children are politicians.) Within the clan system, one man emerges as the chieftain; and that is what Charlie Haughey has been, a clan leader, and he draws upon the innate loyalty and fealty to the chieftain which the clan system always involves. A chieftain may die, fall, or be replaced, but while he is leader his hold over his liegemen contains an element of magical power. Thus, Mr Haughey has not just been the Irish Prime Minister, but the chieftain of the southern Irish clans. His national nickname 'the Boss' underscores this.

All earthly powers pass, and Charlie's have been on the wane for some time now. Moreover, it is widely felt in Ireland that his style of power is ebbing away. Since the election of President Mary Robinson in 1990, the old men, they say, are making way for the new women; and there is a dif- ferent Ireland emerging now which is younger — half the Irish are under 25 — more liberal, more self-consciously mod- ern and European, certainly more femi- nist, and possibly more ashamed of the Tammany Hall style of politics which the Irish have traditionally made their own everywhere. When Charlie Haughey goes, it is said, the 'old' Ireland of pork-barrel politics and the clan chieftain will move into history.

This may be more aspiration than fact. Fianna Fail is a well-honed political ma-

chine, and the roots of any culture take a long time to die. For some years now, par- ticularly in the pages of the Times, Conor Cruise O'Brien has carried out an obses- sive political pursuit of Charles J. Haughey which has sometimes assumed the charac- ter of a vendetta. But when it came to popularity with the man — and particular- ly the woman — in the street, Conor could never hold a candle up to Charlie: at the hustings Conor seemed a remote intellec- tual where Charlie could ever communi- cate through the glad hand. Although his day is over, the people liked Haughey, and when he is gone they will say, as the Irish do: `Ah, sure, he wasn't the worst.' Indeed, no man who would provide a lady with Montrachet could be all bad.

Previous page

Previous page