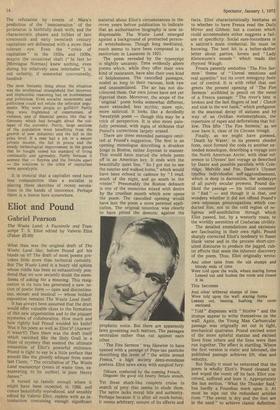

Eliot and Pound

Gabriel Pearson

The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript T. S. Eliot edited by Valerie Eliot (Faber £5.00) What then was the original draft of The Waste Land like, before Pound got his hands on it? The draft of most poems provokes little more than technical curiosity. But The Waste Land is a hoary old sphinx whose riddle has been so exhaustively pondered that we now securely doubt the seemliness of asking for a meaning. This resignation in its turn has generated a new notion of poetic form — open and discontinuous, mosaic and musical — whose boldest exposition remains The Waste Land itself.

It has always been assumed that the draft would offer valuable clues to the formation of this new organisation and to the piquant mysteries of collaboration. How much and how rightly had Pound wielded his knife? Was it his poem as well as Eliot's? (Answer: it wasn't!) Then there was the draft itself which vanished like the Holy Grail in a blaze of mystery that seemed the ultimate emanation of Eliot's powerful reticence. Pound is right to say in a little preface that sounds like the ghostly whisper from some last Canto, "The occultation of The Waste Land manuscript (years of waste time, exasperating to its author) is pure Henry James."

It turned up tamely enough where it might have been expected, in 1968, and comes beautifully reproduced, and sensibly edited by Valerie Eliot, replete with an introduction containing enough significant material about Eliot's circumstances in the Eleven years before publication to indicate that an authoritative biography is now indispensable. The Waste Land emerged against a background of protracted personal wretchedness. Though long meditated, much seems to have been composed in a sanitorium in Lausanne in 1921.

The poem revealed by the typescript is slightly uncanny. Time evidently alters poems which, while they offer their own kind of resistance, have also their own kind of helplessness. The cancelled passages, sealed so long in their vacuum, look raw and unassimilated. The air has not discoloured them. Our own juices have not yet digested them. Moreover, the scope of the ' original ' poem looks somewhat different, more extended, less mythic, more epic, more satirical. It looks like a decidedly 'twentyish poem — though this may be a trick of perspective. It is also more painfully personal, with signs of sickness that Pound's corrections largely erased.

There are three extended passages omitted at Pound's suggestion. The first is an opening monologue describing a drunken binge in Boston, rather Joycean in manner. This would have started the whole poem off in an American key. It ends with the beautifully quiet line, "So I got out to see the sunrise and walked home," which would have been echoed in cadence by "1 read, much of the night, and go south in the winter." Presumably the Boston debauch is one of the memories mixed with desire by the cruellest month which now opens the poem. The cancelled opening would have lent the poem a more personal application. The original intention was clearly to have pitted the demotic against the prophetic voice. But there are apparently laws governing such matters. The passages neutralise rather than cut against each other.

'The Fire Sermon' was likewise to have opened with a passage of Pope-ian pastiche describing the levee of "the white armed Fresca," a high society demi-mondaine poetess. Eliot saws away with surgical fury: Odours, confected by the cunning French, Disguise the good old hearty female stench.

Yet these shark-like couplets cruise in search of prey that seems to elude them. The satire lacks moral bite and authority. Perhaps because it is after all mock-heroic, it seems arbitrary, unsure of its effects and facts. Eliot characteristically hesitates as to whether to have Fresca read the Daily Mirror and Gibbon: but a context which could accommodate either suggests a failure of specificity. Social sure-footedness is a satirist's main credential. He must be knowing. The best bit is a helter-skelter letter about parties, lovers and "Lady Kleinwurm's monde" which reads like rhymed Waugh.

Fresca patently embodies 'The Fire Sermon' theme of "Unreal emotions and real appetite," but its overt misogyny feels out of control. It is with relief that one greets the present opening of 'The Fire Sermon' scribbled in pencil on the verso of a Fresca passage: "The river's tent is broken and the last fingers of leaf / Clutch and sink in the wet bank," which prefigures. in the seasonal decay of autumn and by way of an Ovidian metamorphosis, the repertoire of rapes and deflorations that follow. This lifts 'The Fire Sermon,' as we now have it, clear of its Circean trough.

Finally, as we might have guessed, Death by Water,' in its present slender form, once formed the coda to another extended monologue, describing a voyage into the North American Arctic, with clear reference to Ulysses' last voyage as described by Dante and possible parallels with Coleridge, Melville and Poe. Dante's Ulysses typifies individualist self-aggrandisement, which is deep in damnation, the archetype of all purely secular prowess. Pound disliked the passage — his initial comment is " Bad " — and though it is that, one wonders whether it did not offend Pound's own , odyssean preoccupations which conducted him, not to the cold region of religious self-annihilation through which Eliot passed, but, by a westerly route, to the worldly serenities of Confucian civility.

The detailed emendations and excisions are fascinating in their own right. Pound sharply corrected Eliot's tendency to fluent blank verse and in the process short-circuited discourse to produce the jagged, cubist effects that seem the inherent discovery of the poem. Thus, Eliot originally wrote:

And other tales from the old stumps and bloody ends of time Were told upon the walls, where staring forms Leaned out and hushed the room and closed it in.

This becomes

And other withered stumps of time Were told upon the wall: staring forms Leaned out, leaning, hushing the room enclosed.

" Told " dispenses with " Stories " and the stumps appear to write themselves on the wall. Again, the Young Man Carbuncular passage was originally set out in tight, mechanical quatrains. Pound excised some of the more spiteful stanzas and excised lines from others and the lines were then run together. The effect is startling. Where the first version is static and laboured, the published passage achieves lift, elan and velocity.

But finally it must be reiterated that the poem is wholly Eliot's. Pound cleaned up and wiped the vomit off its face. Eliot conceived, suffered and bore it. Appropriately the last section, What the Thunder Said,' has hardly a Poundian mark upon it. At most he nips out the redundant articles from "The sweat is dry and the feet are in the sand" to achieve classic definition.

Previous page

Previous page