A TALE OF THREE CITIES

Timothy Garton Ash explores the connections

between an election in Warsaw, a funeral in Budapest and a Soviet leader in Bonn

THE general crisis of communism has loosened the bonds of Central Europe. Three remarkable events in so many weeks, one in Germany, one in Hungary and one in Poland, illustrate the giddy pace of change.

At the presidential villa, a schoolgirl called Annette Lang hands him a pfennig and a kopek. This is meant to be a symbol of our friendship,' she explains. Uncle Misha embraces her and kisses her on the cheek. Next day's Bild, the German Sun, carries a front-page picture of the happy pair and the banner headline: 'A kiss for Annette, a kiss for Germany.' It was', explains the story, 'like a kiss for us all.'

Indoors, the serious business: the signa- ture of a long, solemn joint declaration

opening what both sides agree will be a `new chapter' in what Gorbachev carefully calls `Soviet-Federal German' relations. The initialling of no less than 11 other bilateral agreements, ranging from the protection of investments to the installa- tion of a Bonn-Moscow 'hot line'. Earnest speeches about learning from the past, about reconciliation, peace and co- operation in solving common problems. It is, says Mr Gorbachev, the end of the post-war period.

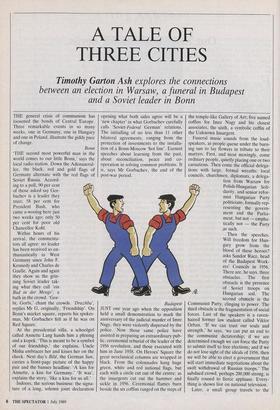

Budapest JUST one year ago when the opposition held a small demonstration to mark the anniversary of the judicial murder of Imre Nagy, they were violently dispersed by the police. Now those same police have assisted in preparing an extraordinary pub- lic, ceremonial reburial of the leader of the 1956 revolution, and those executed with him in June 1958. On Heroes' Square the great neoclassical columns are wrapped in black. From the colonnades hang huge green, white and red national flags, but each with a circle cut out of the centre: as the insurgents cut out the hammer and sickle in 1956. Ceremonial flames burn beside the six coffins ranged on the steps of

the temple-like Gallery of Art; five named coffins for Imre Nagy and his closest associates, the sixth, a symbolic coffin of the Unknown Insurgent.

Then the speeches. Will freedom for Hun- gary grow from the blood of these heroes? asks Sandor Racz, head of the Budapest Work- ers' Councils in 1956. There are, he says, three obstacles. The first obstacle is the presence of Soviet troops on Hungarian soil. The second obstacle --is the Communist Party, clinging to power. The third obstacle is the fragmentation of social forces. Last of the speakers is a raven- haired former law student called Viktor Orban. `If we can trust our souls and strength,' he says, 'we can put an end to the communist dictatorship; if we are determined enough we can force the Party to submit itself to free elections; and if we do not lose sight of the ideals of 1956, then we will be able to elect a government that will start immediate negotiations about the swift withdrawal of Russian troops.' The subdued crowd, perhaps 200,000 strong, is finally roused to fierce applause. Every- thing is shown live on national television.

Later, a small group travels to the remote corner of the cemetery where, some time after the execution, the mortal remains of Nagy and his associates were cast into a common grave. I was here just a Year ago, at this now legendary Plot 301, and as I write I have before me my photographs of the dusty wasteland, and, yes, a rubbish dump where now the ground is at last prepared for decent burial. They have laid a new road to Plot 301, and lined it with a guard of honour. One name is not mentioned in any of the speeches. One name is in everyone's mind. It is the name of Janos Kadar, and Kadar remembered not as the leader of the West's favourite 'liberal' communist coun- try in the 1970s, but as the traitor who took over from Nagy on the back of Soviet tanks, the man who was directly responsi- ble for the murder of Imre Nagy. Where is he today, that sick old king? Is he watching on television? He is Macbeth, and Ban- quo's ghost lies in state on Heroes' Square. This is not the funeral of Imre Nagy. It is the resurrection of Imre Nagy, and the funeral of Janos Kadar.

Warsaw 'REALLY we should start by singing "We, the First Brigade",' says Lech Walesa, referring to the famous marching song of Pilsudski's Polish Legions in the first world war. But the First Brigade he now addres- ses is the group of 260 Solidarity- opposition candidates who won seats in the Polish parliament at the country's first free (although limited) election for more than half a century. They are assembled here in the Auditorium Maximum of Warsaw Uni- versity, shortly after the second round of the election has sealed their triumph. And if Walesa thinks he can behave like Mar- shal Pilsudski he is soon disabused. For when he goes on to lay down what should be the form and leadership of the Solidarity-opposition parliamentary group there is instant revolt. This is 'a sort of coup d'etat', they say, we really cannot start our democracy with these 'Bolshevik methods'.

Walesa instantly retreats. Like everyone else, he has to learn the ways of democracy — especially parliamentary democracy. But he's a quick learner. After an hour and a half of mostly unnecessary debate, his proposals are accepted anyway, but in a properly conducted vote. Professor Bronis- law Geremek, just back from a successful meeting with Mrs Thatcher in London, takes the chair as the first elected leader of the combined parliamentary group. From now on, the proceedings are orderly, effi- cient, and scrupulously put to the vote.

Professor Geremek begins by remarking that he had recently been privileged to attend a parliamentary meeting in 'a West European country' (presumably Britain) and had asked what were the rules of the meeting. He was told there were none. People just knew what to do. But here in Poland, he goes on, we do need rules. And so, in quick succession, they appoint corn-

mittees to work out rules for their new parliamentary group, proposals for changes to the procedural rules of the Sejm (the existing lower house) and the entire procedure for the new upper house, the Senate. The Polish Erskine May.

Then, after debating various alterna- tives, the group gives itself a name: the Citizens' Parliamentary Club. Interesting- ly, proposals to include the word 'Solidar- ity' are rejected at the urging of Solidarity's leader. The times have past when all popular aspirations had to be channelled through the one movement, Walesa says. Diverse political tendencies have already emerged and must find their expression through this group in parliament. Let ordinary politics begin. Ordinary politics, that is, such as would have been quite unthinkable even in Poland until a few months ago.

Three snapshots from a fast-moving scene — so fast-moving in fact, that any analysis is almost certain to be overtaken by events. To say what has ended is easier than to say what has begun. These mo- ments symbolise the end of the post-war period in German-Soviet relations, the end of the post-1956 period in Hungary and the end of communism in Poland. West Ger- many is leaning towards a central role in Europe, while Poland and Hungary are tugging themselves towards the West. Their meeting-place may now be called Central Europe.

On the Polish path there are still huge obstacles. Solidarity has the immediate problems of success. During the negotia- tion of the Round Table agreements which led to the election it was generally under- stood on both sides — although never publicly stated — that General Jaruzelski would take the new powerful post of elected President. The electoral arithmetic seemed to guarantee the Party- government-coalition side a majority for

him in the combined houses of parliament, which, under the changed constitution, elect the President. But so great has been Solidarity's electoral triumph that, with more than 20 MPs on the government- coalition side indicating that they would vote with Solidarity, it may now have a majority against. Yet the real powers-that- be in Poland today, which means the generals of army and police as much as the Party, have so far indicated no inclination at all to accept any compromise candidate. Solidarity's leaders, however, would not be forgiven by many of their supporters if they supported a Jaruzelski candidacy.

If this hurdle is somehow overcome, there is then the question of who forms the government. Suggested variants range from a coalition government, in which there would be a number of Solidarity- opposition ministers, to a Solidarity- opposition government, with the defence, interior and perhaps foreign ministries reserved to the Party. At the moment, the most likely compromise seems to be a Party-led 'government of experts', with the Solidarity group remaining in opposition, but controlling the work of this govern- ment through parliamentary commissions and direct negotiations with the key figures on the Party side. This has been ironically described as 'government by Round Table'. It seems well suited to solving major political disputes, but not to produc- ing a clear, consistent economic policy, which would inevitably cut across one or other of the social interests represented by the Solidarity-opposition side.

And even if this problem of government is resolved at the top, there are still larger tasks lower down: for example, that of democratising the whole of local govern- ment by the nomenklatura of Party appoin- tees. Even the Parliament has no proper non-Party staff. And what about the organ- isation of political parties, constituency organisations for MPs, the press, the radio, television . . ? The list is endless. Every- thing has to be remade.

In Hungary, the pOlitical transformation is not quite so far advanced, but is fast gathering pace. Many people had mixed feelings about the Nagy funeral because it seemed that the authorities had at least partly managed to reclaim the revolution for themselves. One picture that went round the world was of leading Party reformers such as Imre Pozsgay and the Prime Minister Miklos Nemeth standing guard beside the coffin of Imre Nagy. For them this was a gift. They could now say that the whole chapter was closed, and open a new one, with a revamped or even new party, with a new name. Just one week later they effectively toppled the opportun- ist Party leader Karoly Grosz (hailed by Mrs Thatcher only a year ago as a man in her own image), and replaced him with a four-man praesidium in which he is in a minority of one beside three leading refor- mers: Pozsgay, Nemeth and the veteran economic reformer, Rerso Nyers. The re-birth of the Party — like a butterfly from a caterpillar? — is envisaged at this autumn's Party congress.

Beside preparing the congress, and tack- ling the worsening economic mess (so grave that it triggered postponement of a planned IMF transfer), the Party refor- mers' main political task is now to negoti- ate with the new opposition parties and groups the terms and conditions for free elections, probably some time next year. Whereas the Polish communists negotiated with the opposition at a round table, their Hungarian colleagues have to negotiate with a round table: the so-called Opposi- tion Round Table which groups all the main opposition forces in fragile coalition. The Opposition Round Table actually sits on one side of a rectangular table, facing the Party-government side at another, with miscellaneous quangos represented at a third. If all goes well, Hungary will have wholly free elections some time next spring.

Opinion polls currently suggest that a reformed and renamed Party — perhaps simply the Hungarian Socialist Party? unambiguously led by the reformers, might win more than 30 per cent of the popular vote, and therefore be the strongest part- ner in a new coalition government. But the opinion polls in Poland were all wrong, and a year in politics is a very long time. Remember where Hungary was one year ago: the police beating the demonstrators, the rubbish dump where now Imre Nagy and his comrades have decent tombs.

And who can tell what long-repressed feelings, memories and aspirations were awakened at the funeral of Imre Nagy? What happens when a nation which for 30 years has been compelled to forget its revolution is suddenly invited — and that officially — to remember, even to cele- brate? 'This was for us what the Pope's visit in 1979 was for Poland,' says the fiery Viktor Orban.

For both Poland and Hungary the essen- tial internal question is: can you manage an unprecedented political transformation in conditions of economic collapse? The answer to that question depends to a large degree on the West's readiness to help economically, which in turn depends cru- cially on West Germany. So back to Bonn.

West German officials are understand- ably irritated at Western suspicions of `Gorbasin' and `Rapallo'. Look at the crowds on Pennsylvania Avenue during the Washington summit, they say: look at the Sun during Gorby's visit to England. And Rapallo the Joint Declaration certainly is not. But there was a special emotional edge to the visit for four related reasons.

First, West Germany, like Hungary, is not used to great displays of public emo- tion. Secondly, Germany was being for- given if not actually told it could forget the suffering Germans inflicted on the Soviet Union during the second world war. A prominent Soviet panjandrum compared it• to the reconciliation between Adenauer and de Gaulle. Thirdly, Gorbachev here ceremoniously confirmed what George Bush had underlined in Mainz two weeks before: the centrality of West Germany to our new post-postwar Europe (Mrs Thatcher, please note). Finally, there was an unmistakable undertone of hope about a change in relations between the two Germanies, leading eventually, who knows how, to some form of reunification.

reunification.

Mr Gorbachev has made it clear that he has no intention at all of giving away East Germany, although his one important pub- lic reference to that state might almost be construed as ironic. (He spoke of the GDR's 'characteristic consciousness of a special responsibility for the fate of the world'.) At the same time, he has indicated that he would not be at all averse to a GDR version of perestroika and glasnost. If East Germany started to change internally, albeit more cautiously than Poland and Hungary, then Central Europe really would be on the move. Whether that is at all likely I hope to discover next week — in East Berlin.

Timothy Garton Ash was this week awarded the David Watt Memorial Prize of £2,000 for his 'outstanding contributions towards the clarification of international and political issues'.

Previous page

Previous page