SUMMER WINE AND FOOD

Food for the road

Nigella Lawson

IN French Provincial Cooking, Elizabeth David, late of this parish, gives a recipe for petits souffles aux courgettes. 'I first had these little souffles,' she remarks, 'at a lorry drivers' restaurant about three miles from the Pont du Gard. They came after cooked ham and cold vegetables served with a pow- erful atoll, and were followed by a boeuf la gardiane garnished with heart-shaped croutons of fried bread. Then came a home-made ice with home-made almond tuiles. After which the local mart from Chi teauneuf du Pape was a welcome diges tive.'

Even if, as Mrs David makes certain of assuring us, this was not the normal set meal of the café, it is enough to boggle the mind of anyone used to the Little Chef and the Happy Eater. The idea of there being available anything not on the normal menu in the first place is difference enough. Even in France it would probably be hard to eat quite as magnificently as in that little lorry drivers' joint now. And there is a tendency in this country to think that every chef in France or Italy is rhapsodically turning out Michelin-starred food at a couple of pounds a head.

But I remember driving back through Italy and France one year, stopping off in various roadside joints, eating lasagne al forno dished out of large steel pans, proper andouillette and decent steak frites. More recently, I lunched in the dining-room of a motorway hotel on the road from Bari to Naples and had a bowl of maltagliati — produzione propria — with hunks of fleshy pumpkin.

It has become such a truism that the standard of eating has improved enormous- ly over here that we accept it, self-congratu- latorily, without question. At some levels it is without doubt true. There is a remark- able uniformity of excellence at the best restaurants, whether they be in Paris, New York or London.

The produce available at Sainsbury's, the free-range chickens at Tesco, the carefully researched prepared foods at Marks & Spencer, all these are indubitably good. But what you can't seem to find in this country is good cheap food. I don't mean food that exceeds expectation, the wonderful little find: I mean good cheap food that is good cheap food. For all that we sneer at Ameri- ca, it is remarkably easy to eat well on a low budget there. The places are clean, they are reliable, the food's fresh and the customers monitor it.

If we are really serious, as Alastair Little said in a lecture he gave to the University of Surrey Food and Wine Society recently, about improving the quality of food in this country, it's to the lower end of the market we must look. The revoltingness of motor- way food became something of the leitmo-

tiv of the Little lecture. He, too, had fondly remembered, in his book, Make it Simple, an excellent roadside meal abroad. In dis- cussing roast veal, he recalled 'a particular- ly delicious example eaten at the Agip ser- vice station on the autostrada just south of Florence: a thick slice of roasted rump served absolutely plain with only a wedge of lemon and the juices which ran out of it. Not the sort of thing one finds at service stops on a British motorway.'

Indeed my own recent memory of motor- way eating had been of sandwiches so chilled that the slices of bread clung, des- perately, damply together, the filling inde- terminate, the price extortionate. I suggest- ed to Alastair that we do a tour of these much abominated places together. I was interested to see if his prejudices were justi- fied and, besides, he's good company. So I bundled him off in a car at 8.30 one morn- ing and we hit the road.

I should say that Alastair is not one of those chefs who mistakes a label-conscious foodism for love of eating. Nor is he one of those tiresomely uncompromising artists either: he comes from Lancashire and understands about proper food. He under- stands, too, about improper food. We were once travelling on a train together to Manchester and spent much of the time arguing about whether a fish-finger sand- wich is better with or without ketchup. He's a genuinely good cook and a self-taught one, he understands the properties of food and how one best enjoys them. And, like a lot of people who come from `oop north', he clings tenaciously to the sentimental image of his rough-hewn origins: he favours the robust approach, and the sweat of a

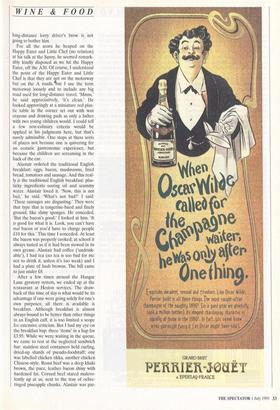

WINE & FOOD

long-distance lorry driver's brow is not going to bother him.

For all the scorn he heaped on the Happy Eater and Little Chef (no relation)

at his talk at the Savoy, he seemed remark- ably kindly disposed as we hit the Happy Eater, off the A30. Of course, I understand the point of the Happy Eater and Little Chef is that they are:lot on the motorway but on the A roads,"but I use the term motorway loosely and to include any big road used for long-distance travel. `IVImm,' he said appreciatively, 'it's clean.' He looked approvingly at a miniature red plas- tic table in the corner set out with wax crayons and drawing pads as only a father with two young children would. I could tell a • few non-culinary criteria would be applied in his judgments here, but that's surely admissible. One stops at these sorts of places not because one is quivering for an ecstatic gastronomic experience, but because the children are screaming in the back of the car.

Alastair ordered the traditional English breakfast: eggs, bacon, mushrooms, fried bread, tomatoes and sausage. And this real- ly is the traditional English breakfast: plas- ticky ingredients oozing oil and scummy water. Alastair loved it. 'Now, this is not bad,' he said. 'What's not bad?' I said: `These sausages are disgusting.' They were that type that is tangerine-hued and finely ground, like slimy sponges. He conceded, `But the bacon's good.' I looked at him. 'It is good for what it is. Look, you can't have real bacon or you'd have to charge people £10 for this.' This time I conceded. At least the bacon was properly cooked; at school it always tasted as if it had been stewed in its own grease. Alastair had coffee (`undrink- able'), I had tea (no tea is too bad for me not to drink it, unless it's too weak) and I had a plate of hash browns. The bill came to just under £8.

After a few times around the Hangar Lane gyratory system, we ended up at the restaurant at Heston services. The draw- back of this time of day is what would be its advantage if one were going solely for one's own purposes: all there is available is breakfast. Although breakfast is almost always bound to be better than other things in an English caff, it is too limited a scope for extensive criticism. But I had my eye on the breakfast bap: three 'items' in a bap for £3.95. While we were waiting in the queue, we came to rest at the neglected sandwich bar: stainless steel containers held curling, dried-up shards of pseudo-foodstuff; one was labelled chicken tikka, another chicken Chinese-style. Roast beef was a deep khaki brown, the puce, leather bacon shiny with hardened fat. Corned beef stared malevo- lently up at us, next to the tray of ochre- tinged pineapple chunks. Alastair was par- ticularly fond of the special label with Flora printed on it over the container of individu- al margarine sachets.

`One breakfast bap,' I said cheerily, `bacon, black pudding, fried egg!' You're not . ? ' said Alastair. `I am,' said I; `duty, Alastair.' We walked silently back to the table, Alastair solemnly cut the bap in half. Reader, it was delicious. 'In the right frame of mind, it could be edible,' said Alastair. `It's much better than that!' I felt indignant on its behalf. He agreed he'd been ungen- erous. We both carried on taking small bites, neither of us wanting to look quite as greedy as to want to finish it. 'One of my first jobs was in a mill in Lancashire,' said Alastair. `I had to fetch everyone's teas, and they'd all have baps — only we call them tea-cakes — with egg and bacon and fried bread in them.' We sat in silent, apprecia- tive✓ wonder of fried bread as a filling in a sandwich, and then rode off to the next stop.

This found us in the Granada Scratch- wood service area, in a virulently urban set- up called the Granary Barbecue, as they all are these days. It was moving out of break- fast time, so a few other choices came in to play. I ordered a macaroni bolognese (£4.50) and the man behind the counter opened a square packet and put it in the microwave. Alastair took a cafetiere of cof- fee (£1.35), which he then began praising extravagantly, and we sat and waited. The man approached with the bowl, the packet tidily decanted into it. `Do you want parme- san?' he asked. 'No!' I shouted violently, too afraid of the grated feet in the plastic cylinder to remember to sound reasonable. `Yes, please,' said Alastair. It came, was not too bitter, I ate. `Not too bad,' I said cau- tiously. `George would love this,' said Alas- tair. George is his seven-year-old son. But after a few tubes of the stuff we gave up: we couldn't make a convincing job out of enjoying this.

The trouble is, because we all know so well what sort of food we'll get in these places we don't expect it to be any better, and so we don't question it when it comes. There's no reason why we can't have over here properly cooked, rather than prepack- aged and nuked, pasta just as they do in Italy. But I suspect the reason we don't is not because it would be too expensive or too difficult to prepare, but because no one cares much.

We split. To revive my spirits, I went back to Alastair's restaurant and had lunch there: sausages, hot and spicy and almost round in their fat bulgingness, a slice of pizza with freshly sliced buffalo mozzarella on it, rump of lamb with flageolet beans and a glass of champagne. We called it a day.

But phoenix-like I rose again: this time not with Alastair but with one baby and one husband (for whom motorway food is very heaven) in tow. It was lunchtime, so we thought we'd go to the Little Chef. They make a deal out of being good at feeding children. Most of the places now are ham- burger joints, McDonald's or Burger King (`At least you know you can get an edible product,' Alastair had said) and a spatter- ing of TGI Fridays, or maybe there was just the one which we seemed to keep on pass- ing.

Somewhere off the M25, near Brockets Wood, we found a Little Chef and went in, by this time with an extremely hungry child. The place was thick with smoke, acrid and stinging. We ordered a dish of baked beans for the baby (my precious is used to ravioli stuffed with wild mushrooms) and an Olympic feast (a 3oz steak with bacon, sausage, eggs, onion rings and fried tomato, £5.99) and a griddled fillet of fish (£5.10) and sat and waited. I was too shocked by the filth of the place to manage to talk about it. Our tea arrived; the cups had a raised pattern of splattered-on tanniny spit around the edges. I thought that if I didn't mention it, it might not really be there. We waited. 'Can't we at least have the baby's food?' I asked, impotently watching her suck on a blackly greasy high-chair strap. A gormless youth moved slowly into the kitchen. After 20 minutes of our ordering, Cosima's baked beans arrived. Five minutes later our food did. I practically cried.

`Sorry it took so long,' said the waitress. `Why,' my husband asked `does it take twenty-five minutes to cook this?'

`Was it really twenty-five minutes?'

My husband told her what time we'd come in, what time it was now and showed his watch in a caricatural display of proof.

`Oh, that's good then. I thought it'd been longer. That's how long it's s'posed to take.'

Everything that could have been wrong here was wrong. Quite apart from the foul smokiness of the atmosphere, it was hope- less for children. A particularly irritating touch was the array of sweets thoughtfully laid out at toddler-shoulder height. By the time we left, I had a splitting headache.

`What I don't understand,' I complained, in the back of the car, angrily, as if this whole expedition hadn't been my idea, Is why someone can't do plain food that tastes good. If anyone did pizza a taglia here, they'd make a fortune.'

We went to the Granada services at South Mimms, a very modern kind of motorway stop-off. They'd evidently been listening to me. The place is rather like the food floor of an American mall: a big space divided into different outlets. Caffe Primo serves coffee and cakes — real cakes, from the Maison Blanc, Julie's is a burger joint, Sbarro is the Italo-American pasta and pizza place, La Baguette is, as you'd expect, a concession devoted to the purveying of fancy sandwiches, and there's a Granary barbecue again. At Sbarro we had a slice of pizza (too much topping, too much dough, but my husband said I was being unfair) and at Caffe Primo a cake and a milkshake. There was a big, airy children's play area and a chemist (called, American-style, a drugstore) where I could buy something to get rid of the headache I'd contracted at the Little Chef.

Talking of which, there was also a Little Chef at this superama new-style motorway service station —and what do you think? This is what the biggest queues were for. No wonder the big operations don't bother. You try and give them good food and they, like our Prime Minister, want the Little Chef.

Previous page

Previous page