ARTS

Exhibitions 1

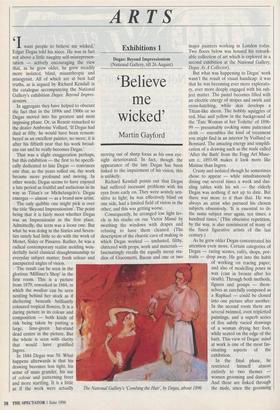

Degas: Beyond Impressionism (National Gallery, till 26 August)

'Believe me wicked'

Martin Gayford

Iwant people to believe me wicked,' Edgar Degas told his niece. He was in fact not above a little naughty self-misrepresen- tation — actively encouraging the view that, as he grew older, he grew steadily more isolated, blind, misanthropic and misogynist. All of which are at best half truths, as is argued by Richard Kendall in the catalogue accompanying the National Gallery's exhibition Degas: Beyond Impres- sionism.

In aggregate they have helped to obscure the fact that in the 1890s and 1900s or so Degas moved into his greatest and most imposing phase. Or, as Renoir remarked to the dealer Ambroise Vollard, 'If Degas had died at fifty, he would have been remem- bered as an excellent painter, no more; it is after his fiftieth year that his work broad- ens out and he really becomes Degas.'

That was a slight exaggeration perhaps, but this exhibition — the first to be specifi- cally dedicated to late Degas — convinces one that, as the years rolled on, the work became more profound and moving. In other words, Degas seems to have enjoyed a late period as fruitful and audacious in its way as Titian's or Michelangelo's. Degas emerges — almost — as a brand-new artist.

The only quibble one might pick is over the title 'Beyond Impressionism'. The point being that it is fairly moot whether Degas was an Impressionist in the first place. Admittedly, the term was a loose one. But what he was doing in the Sixties and Seven- ties surely had little to do with the work of Monet, Sisley or Pissarro. Rather, he was a radical contemporary realist melding won- derfully lucid classical draughtsmanship to everyday subject matter, fresh colour and unexpected angles of vision.

The result can be seen in the glorious 'Milliner's Shop' in the first room. This is a picture from 1879, reworked in 1884, in which the modiste can be seen nestling behind her stock as if sheltering beneath brilliantly coloured tropical flowers. It is a daring picture in its colour and composition — both kinds of risk being taken by putting a large, lime-green hat-stand dead centre in the picture. But the whole is seen with clarity that would have gratified Ingres.

In 1884 Degas was 50. What happens afterwards is that his drawing becomes less tight, his sense of mass grander, his use of colour and patterning freer and more startling. It is a little as if the work were actually moving out of sharp focus as his own eye- sight deteriorated. In fact, though the appearance of the late Degas has been linked to the impairment of his vision, this is unlikely.

Richard Kendall points out that Degas had suffered incessant problems with his eyes from early on. They were acutely sen- sitive to light; he was effectively blind on one side, had a limited field of vision in the other, and this was getting worse.

Consequently, he arranged low light lev- els in his studio on rue Victor Masse by swathing the windows with drapes and refusing to have them cleaned. (The description of the chaotic cave of making in which Degas worked — undusted, filthy, cluttered with props, work and materials — fascinatingly recalls the equally messy stu- dios of Giacometti, Bacon and one or two The National Gallery's 'Combing the Hair; by Degas, about 1896 major painters working in London today. Two floors below was housed his remark- able collection of art which is explored in a second exhibition at the National Gallery, Degas As A Collector).

But what was happening to Degas' work wasn't the result of visual handicap: it was that he was becoming ever more explorato- ry, ever more deeply engaged with his sub- ject matter. The pastel becomes filled with an electric energy of stripes and swirls and cross-hatching, while skin develops a Titian-like sheen. The bobbly squiggles of red, blue and yellow in the background of the 'Tate Woman at her Toilette' of 1896- 99 — presumably evoking some patterned cloth — resembles the kind of treatment you might find in an interior by Vuillard or Bonnard. The amazing energy and simplifi- cation of a drawing such as the nude called 'After the Bath' from the Fogg Art Muse- um c. 1893-98 makes it look more like Matisse than Ingres.

Crusty and isolated though he sometimes chose to appear — while simultaneously dining out several times a week and daz- zling tables with his wit — the elderly Degas was nothing if not up to date. But there was more to it than that. He was always an artist who pursued his chosen subjects obsessively. 'It is essential to do the same subject over again, ten times, a hundred times.' (This obsessive repetition, by the way, is also reminiscent of many of the finest figurative artists of the last century.) As he grew older Degas concentrated his attention even more. Certain categories of Degas — racing scenes, cafés, shops, por- traits — drop away. He got into the habit of working on tracing paper, and also of modelling poses in wax (cast in bronze after his death). Through both methods, figures and groups — them- selves as carefully composed as a Raphael — could be cloned into one picture after another. In the second room there are several twinned, even tripletted paintings, and a superb series of five subtly varied drawings of a woman drying her foot, while seated on the edge of the bath. This view of Degas' mind at work is one of the most fas- cinating aspects of the exhibition.

In the final phase, he restricted himself almost entirely to two themes — women grooming and dancers. And these are linked through the nude, since the grooming women are generally naked, and the dance pictures are based on nude studies. It was the female body in motion above all that interested him. The astonishing sequence of women bathing fills the central gallery, and it is at the heart of the exhibition.

This visual obsession clearly leaves the aims of the elderly bachelor artist open to misinterpretation. One of the pictures on show — from the National Gallery in Edin- burgh — is on the cover of a widely remaindered book entitled Erotic Art. Simi- larly, their pictures have been subject to misplaced feminist denunciation. Degas was not engaged in producing erotica, and the nearest he came to sexual harassment of his models was to waltz once round the room in a moment of high spirits while singing an air from an Italian opera.

He was trying to see the human body freshly, directly, without cliché. This is a task of enormous difficulty, requiring end- less pains. It was because he succeeded that it was once thought that these were delib- erately ugly pictures made by a man who hated women. And it was because he suc- ceeded that these now strike us as some of the most exhilarating images of the human body ever achieved.

Previous page

Previous page