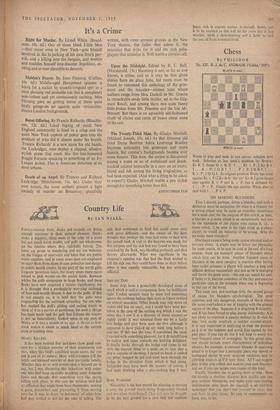

Chess

By PHILIDOR

No. 125. B. J. da C. ANDRADE (`Tablet,' 1957) BLACK (6 men) WHITE (,8 men) WHITE to play and mate in two moves: solution next week. Solution to last week's problem by Bruma: Kt-K 2, threat Q x K P. 1 . . Kt x P; 2 Kt-B 4.

I B x P; 2 Q-B 7. 1 ...P x P; 2 B-B 4. 1 ... K x P; 2 Q-Q 4. In original position White has mate against Kt x P (2 Kt-B 4): the 'try' Kt-13 2 gives mates also against B x P and K x P, but is defeated by I . . . P x P. Finally the key enables White also to

deal with I. P x P.

ON MAKING BLUNDERS

First I should, perhaps, define a blunder, and such a definition must be subjective, for what is a blunder for a strong player may be quite an everyday occurrence for a weak one; for the purpose of this article, at least, a blunder is a move which is an exceptionally bad one by the standards of the player who makes it, i.e., a move which, •' he were in his right mind as a chess- player, he would sec instantly to be wrong. Why do we make these blunders?

One major cause is being under undue physical and/or nervous strain. A player may be below par physically for some reason, or he may be tired at the end of a long session; these are standard causes of blunders about which little cats be done. Another frequent cause of blunders in the same category is reaction after having been under pressure: a player will conduct a long and difficult defence successfully and just as he is emerging will throw the game away—this one can watch for and, if liable to it, become conscious of the fact and exercise particular care at the moment when one is beginning to feel out of the wood.

This leads into, and overlaps with, the second group

of causes for blunders—psychological. The most common, and very dangerous, example of this is where the move overlooked is out of keeping with the general, nature of the play. Suppose A is attacking B violently, and B has been forced to play purely defensively; A is not likely to overlook a passive defence by B—but he may very easily overlook a sudden counter-attack. It is very important in analysing to treat the position as it is at the moment and avoid, bias caused by the past play: if you can do this it will help to avoid this very frequent cause of oversights. In this group also, one should include errors characteristic of individual players: for example, a common blunder in analysing ahead is to forget that a particular piece was moved or exchanged earlier in your analysed variation, and to continue analysis as if it were there. All I can suggest here is that you collect and analyse your own blunders and see if you can isolate root causes of this kind.

Finally, blunders due to getting short of time. Here the remedy is obvious: discover how quickly you can play without blundering and make quite sure (setting intermediate time limits for yourself is an excellent technique) that you don't run yourself so short that you have to play faster. So easy to recommend—so hard, alas, to do.

Previous page

Previous page