No one knew more than Regy

Robert Blake

THE ENIGMATIC EDWARDIAN: THE LIFE OF REGINALD 2nd VISCOUNT ESHER by James Lees-Milne

Sidgwick & Jackson, f15

Reginald (Regy) Brett second Vis- count Esher, son of the Master of the Rolls, was a well-known figure behind the political scene of the late Victorian, Edwardian and early Georgian period. He appears in most of the memoirs and corres- pondence of the time, friend and adviser of kings, queens, princesses, statesmen, admirals, generals — nearly everyone who counted. He died in 1930 at the age of 78. Why has his biography not been written earlier? The answer, according to rumour, is that more than one author has been invited but after seeing Esher's diaries and letters, or enough of them, has developed cold feet. Esher was fundamentally homosexual from his Eton days onwards, and his papers reveal a series of infatua- tions. For example, of an Eton boyfriend when both were staying at a country house he writes: We had one long kiss under the moor- shadows. We have stood lip to lip, under the woodland by the murmuring Torridge. I have kissed him in every room in Halsdon. Five days of free and unconfined love. Our rooms are opposite and he wanders in and out quite easily and simply.

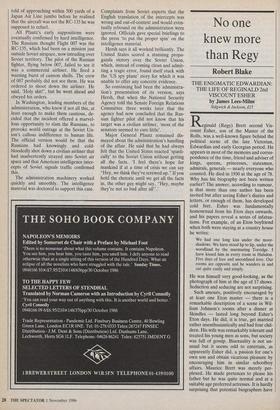

He was himself very good-looking, as the photograph of him at the age of 17 shows. Seduction and seducing are not surprising.

Such amours, positively encouraged by at least one Eton master — there is a remarkable description of a scene in Wil- liam Johnson's rooms after a dinner at Skindles — lasted long beyond Esher's Eton days. He did, it is true, get married rather unenthusiastically and had four chil- dren. His wife was remarkably tolerant and treated his young men as sons, but society was full of gossip. Bisexuality is not un- usual but it seems odd to entertain, as apparently Esher did, a passion for one's own son and obtain vicarious pleasure by encouraging him in similar schoolboy affairs. Maurice Brett was merely per- plexed. He made pretences to please his father but he was quite normal and at a suitable age preferred actresses. It is hardly surprising that potential biographers have been put off by this bizarre background. Esher was not an author, like Maugham, or an intellectual, like Keynes. He was a grand establishment figure. To reveal the facts might be embarrassing, to suppress them would be disingenuous.

Mr James Lees-Milne, with the full cooperation of the family, has written an excellent biography which is also a peg on which to hang a fascinating account of most of the major scandals of the day for Esher knew everything about all of them. For the first time we have a clear picture of a remarkable person whose influence on affairs is difficult to quantify but is general- ly agreed to have been important. He was politically Liberal and began as Lord Hart- ington's private secretary; he became member for Penryn and Falmouth in 1880. He was not a debater but, as the author puts it, 'flourished in a society where intrigue, plot and counterplot were the machinery of daily life'. He lost his seat in 1885, but he never lost the art of intrigue. Having wisely built a house in 1884 close to the edge of Windsor Great Park he soon became a member of Queen Victoria's private circle, but he already seems to have belonged to almost every private circle that mattered. In 1886 Harcourt consulted him about accepting the Exchequer, Rosebery the Foreign Office and Morley the Irish Secretaryship. In the same year Labouchere offered him the editorship of the Daily News which he declined. He would have done the job admirably. The late Victorian era was as full of leaks, scandals and indiscretions as our own. They were not given the same mass public- ity but the elite knew and editors wrote with that knowledge. No one knew more than Regy, but he aimed at higher things.

Rosebery offered him the Office of Woods and Forests. He vacillated and it went elsewhere but he accepted the post of secretary to the Office of Works which was non-political, did not change with the government, brought him into even closer touch with royalty and gave him a golden opportunity of exercising power behind the scenes. He organised Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and later edited her letters. His high tide came in the reign of her successor. He was on the closest terms with Edward VII who continually sought his advice which was almost always sensi- ble and perceptive. During his reign Esher chaired the War Office Reconstruction Committee (the Esher Committee) which among other things led to the rebirth of the Committee of Imperial Defetice on which he also served. His influence on defence policy was his most important contribution to public life. He was offered successively the posts of permanent under secretary at the War Office, governor of Cape Colony, secretary of state for war, and viceroy of India. Why did he refuse them all? He did not need the money, but that was not the only reason. He maintained that office would interfere with his vie intime. He had seen the disastrous effects upon Rosebery of fear of disclosures about a private life widely believed to be characterised by similar inclinations. Above all he loved to pull the strings, and he always over- estimated the power of the Crown. George V did not grant him the same intimacy, though Esher served him no less loyally than he had served his father and grand- mother. Perhaps he bombarded him with too many letters of advice. Royalty are not always conspicuous for gratitude. The King made no mention of Esher's death in his diary, merely recording as usual the direc- tion of the wind and the figures on his barometer and thermometer.

Previous page

Previous page