KILLING AN ARAB

William Dalrymple hears

the true story of the seven deaths of Abu-Zeid

Ramallah, West Bank `ABU-ZEID — God burn his bones! was a very clever man.'

Tariq re-arranged his shift and twirled his worry beads around his index finger: `Ya Allah! he escaped us six times! Six times! But we got him in the end.'

`I saw it with my own eyes,' said Urn- Mohammed, who had appeared under the trellising bearing a little bowl of humus. She was a big woman and wore a big blue dress trussed at the waist with a broad white sash. 'It was a few days before the last olive season. I was coming back from my brother's house early in the morning when I noticed Abu-Zeid's car coming along the Ariel road. As he reached the roadblock two shabab [militants] leapt out from behind a wall and — pfoo! peppered his car with Uzi guns.'

Um-Mohammed's face exploded into a broad grin.

`Abu-Zeid tried to reverse and escape, but he hit a wall and they got him all the same. He died in great pain. I was so happy.'

`They poured gasoline over the car and burned it,' said Tariq, also smiling. `After his earlier escapes they were worried he could survive even 30 bullets in the chest.' `We had begun to think he was some kind of djinn,' said Usamah, Tariq's nephew. 'We thought he would never die.'

`But do you know the strange thing?' added Tariq, scooping up some humus on a piece of pitta bread and popping it into his mouth. `Because he was half-negro, the smoke was as black as pitch. The place where he died . . . nothing grows there.'

He raised his eyebrows and gave his beads a twirl.

`You've never heard the story of the seven deaths of Abu-Zeid?' he asked.

Not any version that I believe,' I said. The story had become transformed into a folk tale — a kind of Palestinian Seven Labours of Hercules — in the space of a single year. 'Tell me what really hap- pened.'

`It's a long story,' replied Tariq. 'You have time?'

`Certainly.'

I had been wanting to get to Biddya to hear the true story of Abu-Zeid ever since I had first started hearing heavily embroi- dered versions of the tale in the coffee- houses of Ramallah. It was not easy. The village was nearly always under one of its habitual curfews: most recently as punish- ment for a molotov cocktail lobbed at a passing Israeli army patrol. But at six that morning I had been rung by Usamah and told that the curfew had been lifted until noon. He told me to get ready; he would pick me up at seven.

We drove out of Ramallah past an avenue of army checkpoints — little bird's nests of Uzi and razor-wire — and out into the Palestinian countryside. Many of the valleys appeared at first to be empty — dry hillsides whose pale rocks were scattered like lumps of feta cheese amongst the scrub-gorse — but as you wound your way down the slopes, forms began to take shape: the stone roofs of a steading hidden by an olive grove, the domes of an aban- doned caravanserai, the minaret of a ruined mosque. It was a familiar Mediterranean picture; the same olive slopes form the background to a hundred Tuscan frescoes, and, nearly a millennium before those, to the landscape mosaics of the Ummayad Mosque in Damascus.

Only a mile before Biddya did the scene change. Turning the bend of a dry wadi we saw Settlement Ariel, at first glimpse a great construction site, all cranes and half-built apartment blocks, fitting as dis- creetly into the mediaeval landscape as an electric guitar into a traditional string quartet. Round the town stretched a high- tension razor-wire fence, and above that rose a long line of identical egg-box houses. Usamah jerked his head towards it.

`That was my grandfather's land,' he said. 'The Israelis took it in 1968. We've never received any compensation.'

Since Israel seized the West Bank from Jordan in 1967, settlers have expropriated no less than 60 per cent of the land and built there 130 Israeli-style Milton Keyneses: modern suburban towns with shopping arcades, sports centres and su- permarkets. Ariel is the largest of these Jewish-only settlements, home now to 8,000 Israelis, but projected ultimately to house at least 100,000 — a gloomy pros- pect for Biddya which, sited precariously beneath the town, looks certain to be eventually requisitioned for new housing estates. This year a further series of olive groves separating the village from the settlement were seized. They were bull- dozed to provide room for the 1,000 new houses being built for the latest wave of Jews fleeing European racism — this time Russian anti-Semitism.

The intifada was the response of West Bank villagers to this piece by piece seizure of their ancestral land, and of West Bank villages none was more militant than Bid- dya. Palestinian flags were raised on the power lines, demonstrations mounted, stones thrown. Faced with this sort of defiance, the Israelis could have placed the village under rigorous martial law. This would certainly have limited the trouble, but would have been time-consuming and expensive. Far less effort was the option of controlling the village through a client mukhtar (mayor) who, in return for power over the village, would keep order for his Israeli masters.

In Biddya the authorities tried both methods. In the person of Abu-Zeid they found a Palestinian willing to act as their puppet, and for seven years he ruled Biddya as a tyrant. Since his death the Israelis have been forced to rule Biddya directly. Neither method has managed to subdue the village, but together they have succeeded in ruining it. Of a total popula- tion of 3,330, 500 villagers (most of the younger generation) are currently in pris- on, and 40 families have had their houses destroyed. Moreover, after every incident the army cut down a grove of olives: so far 2,000 trees have gone, and only a few trees remain. Ninety per cent of the village's income used to come from its olives, and Biddya is now bankrupt.

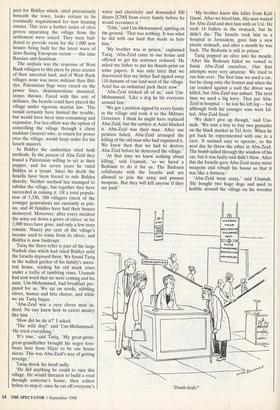

Tariq the Story-teller is part of the large Nasbeh clan which had ruled Biddya until the Israelis deposed them. We found Tariq in the walled garden of his family's ances- tral house, tending his old musk roses under a trellis of tumbling vines. Usamah had sent word that we were coming and his aunt, Um-Mohammed, had breakfast pre- pared for us. We sat on stools, nibbling olives, humus and feta cheese, and while we ate Tariq began.

`Abu-Zeid was a very clever man in- deed. No one knew how to extort money like him . .

`How did he do it?' I asked.

'The wild dog!' said Urn-Mohammed. 'He tried everything.'

'It's true,' said Tariq. 'My great-great- great-grandfather brought his negro fore- bears here from Hijaz to be our house slaves. This was Abu-Zeid's way of getting revenge.'

Tariq shook his head sadly.

'He did anything he could to ruin this village. He would threaten to build a road through someone's house, then collect bribes to stop it; once he cut off everyone's water and electricity and demanded 500 dinars [£700] from every family before he would reconnect it.'

`Tchk,' said Um-Mohammed, spitting on the ground. 'That was nothing. It was what he did with our land that made us hate him.'

'My brother was in prison,' explained Tariq. 'Abu-Zeid came to our house and offered to get his sentence reduced. He asked my father to put his thumb-print on some papers. It was only later that we discovered that my father had signed away 110 dunums of our land west of the village. Ariel has an industrial park there now.'

'Abu-Zeid tricked all of us,' said Urn- Mohammed. 'Like a dog he bit everyone around him.'

'We got a petition signed by every family in the village and took it to the Military Governor. I think he might have replaced Abu-Zeid, but the settlers at Ariel blocked it. Abu-Zeid was their man. After our petition failed, Abu-Zeid arranged the killing of the old man who had organised it. We knew then that we had to destroy Abu-Zeid before he destroyed the village.'

'At that time we knew nothing about killing,' said Usamah, 'so we hired a Bedouin to do it for us. The Bedouin collaborate with the Israelis and are allowed to join the army and possess weapons. But they will kill anyone if they are paid.' 'My brother knew this killer from Kafr Qasni. After we hired him, this man waited for Abu-Zeid and shot him with an Uzi. He took 14 bullets in the stomach, but he didn't die. The Israelis took him to a hospital in Jerusalem, gave him a new plastic stomach, and after a month he was back. The Bedouin is still in prison.'

Tariq popped an olive into his mouth: `After the Bedouin failed we vowed to finish Abu-Zeid ourselves. Our first attempts were very amateur. We tried to run him over. The first time we used a car, but he clung onto the bonnet and when the car crashed against a wall the driver was killed, but Abu-Zeid was unhurt. The next time we used a big lorry. That put Abu- Zeid in hospital — he lost his left leg — but although both his younger sons were kil- led, Abu-Zeid lived.'

'We didn't give up though,' said Usa- mah. 'We sent a boy to buy two grenades on the black market in Tel Aviv. When he got back he experimented with one in a cave. It seemed easy to operate, so the next day he threw the other at Abu-Zeid. The bomb sailed through the window of his car, but it was faulty and didn't blow. After this the Israelis gave Abu-Zeid many more weapons and rebuilt his house so that it was like a fortress.'

'Abu-Zeid went crazy,' said Usamah. 'He bought two huge dogs and used to hobble around the village on his wooden 'Death-beds?' leg, patrolling with the rottweilers, his brother, and his two remaining sons. They beat anyone they found on the streets after dark.'

'Abu-Zeid promised: "Before the next olive season I will have destroyed this village." People said he had gone insane. He blew up the olive press we had been given by the Jordanians before '67, then began cutting down the olive trees of all those he thought were his enemies. But he didn't run away. He knew we would try again, and wherever he went we would find him and kill him.'

`The fifth attempt was a mass attack,' said Usamah. 'The intifada had begun and the shabab had formed hit squads. On 6 March at eight o'clock the shabab attacked his house with molotov cocktails. Their object was to blow him up by igniting the gas canisters which he kept in his garage. But they didn't know the Israelis had given the garage new metal doors. As they tried to break in, Abu-Zeid hobbled up onto his roof and began picking them off with his gun. After he had killed four, the village imam broadcast an appeal for help on the mosque loudspeakers. The whole village rushed out onto the street and joined in. There must have been 700 people out there.'

`But we didn't get anywhere,' said Tariq gloomily. 'While we all went off to evening prayers, one of Abu-Zeid's sons escaped out the back and ran to Ariel. When prayers were over, we managed to get into the garage and blow up his car, but before we could do anything more the settlers arrived. They were all armed, and began firing into the crowd. Later when the army came, they put the village under curfew, arrested 100 and demolished . . . I don't know how many houses.'

`Ya Allah!' said Um-Mohammed, re- arranging her white calico chador. 'There wasn't a woman in the village who wouldn't have gladly strangled Abu-Zeid after that.'

'It's true,' said Tariq. 'But we thought that he would not suspect this. So on the sixth attempt one of my nephews dressed up as a Palestinian woman and went to Abu-Zeid's house with a basket of fruit on his head. Abu-Zeid was sitting outside with Zeid, his eldest son. My nephew put the basket down, pulled out a pistol from under the figs and fired six shots from 20 metres. He hit both men and killed Zeid, but only succeeded in taking off Abu- Zeid's left arm and wounding him in the stomach — again. He was 15 days in intensive care and they had to give him a new arm and plastic intestines, but within a month he was back.'

`So you understand now why were so pleased when we finally got him on the seventh attempt?' asked Urn-Mohammed.

`After we killed him and made a fire of his body the Yahoodi [Jewish] settlers saw the smoke and came running again, but they were too late. There was only a burned skull, a leg bone and a plastic sludge left of Abu-Zeid. All they could do was put him in a sack and give it to his wife.'

Um-Mohammed giggled.

'She threw it out onto a rubbish tip. He had another woman in Kifi Harith, and his wife hated him as much as the rest of us.'

`The army put the village under curfew for two weeks,' said Tariq. 'We couldn't even harvest our trees. But no one minded. Inside every house it was like a holiday. People were singing and dancing.'

'Even in the prisons there was rejoicing,' said Um-Mohammed. 'All Abu-Zeid's old enemies there were about 200 of them in jail at that time — they had a big party also.'

I got up and said my goodbyes while Usamah hurried me out to the car. We drove out of the village and past the gate of Ariel. Under the razor-wire the bulldozers were at work clearing the village's olive groves.

'It was a great day for the village when we killed Abu-Zeid,' said Usamah. 'But in the long run what difference does it make?'

He pointed to a pile of uprooted trees lying at the roadside.

`Such trees are 150 years old — three times the age of the state of Israel. Like us the trees have deep roots in this soil. Now they are uprooted, and with or without Abu-Zeid we will be next.'

Previous page

Previous page