Exhibitions

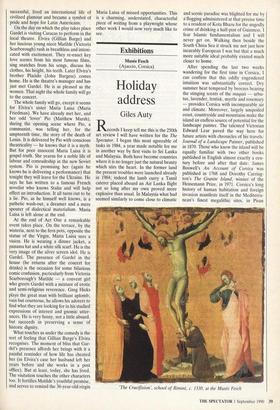

Musee Fesch (Ajaccio, Corsica)

Holiday address

Giles Auty

Records I keep tell me this is the 250th art review I will have written for the The Spectator. I began this most agreeable of tasks in 1984, a year made notable for me in another way by first visits to Sri Lanka and Malaysia. Both have become countries where it is no longer just the natural beauty which stirs the heart. In the former land the present troubles were launched already in 1984; indeed the lamb curry a Tamil caterer placed aboard an Air Lanka flight not so long after my own proved more explosive than usual. In Malaysia what had seemed similarly to come close to climatic

and scenic paradise was blighted for me by d flogging administered at that precise time to a resident of Kota Bharu for the ungodly crime of drinking a half-pint of Guinness. I fear Islamic fundamentalism and I will never get on. Walking then beside the South China Sea it struck me not just how incurably European I was but that a much more suitable ideal probably existed much closer to home.

After spending the last two weeks wandering for the first time in Corsica, I can confirm that this oddly engendered intuition was substantially correct. Dry summer heat tempered by breezes bearing the stinging scents of the maquis — arbu- tus, lavender, lentisk, myrtle and rosemary — provides Corsica with incomparable air and climate. Moreover, largely unspoiled coast, countryside and mountains make the island an endless source of potential for the landscape painter. The talented Victorian Edward Lear paved the way here for future artists with chronicles of his travels: Journal of a Landscape Painter, published in 1870. Those who know the island will be equally familiar with two other books published in English almost exactly a cen- tury before and after that date: James Boswell's An Account of Corsica was published in 1768 and Dorothy Carring- ton's The Granite Island, winner of the Heinemann Prize, in 1971. Corsica's long history of human habitation and foreign invasion manifests itself in the Mediterra- nean's finest megalithic sites, in Pisan The Crucifixion', school of Rimini, c. 1330, at the Musee Fesch

churches and Genoese forts. In the mean- time, the island's famed tradition of the vendetta based on murderous implacabil- ity, often for an imagined slight, may excite anthropologists by providing a likely pathological precedent for the behaviour of certain football supporters or East End thugs: Was you looking at me sister, mister?' The similarities are remarkable.

For those who prefer to reflect on more uplifting matters, I am pleased to report the reopening in Ajaccio two months ago of the wonderful Musee Fesch. The collec- tion takes its name from Cardinal Fesch (1763-1839), Archbishop of Lyons and half-brother of Napoleon's mother, and is to be found in Ajaccio in the street bearing the cardinal's name. I did not know the collection before but can report that the expensive refurbishment of the building looks superb. About some of the works themselves I am slightly more hesitant. I imagine quite a few were in poor condition once but do not know whether it is some of the recent or earlier cleaning which looks to have been too vigorous. Skilled framemakers, too, have done their stuff; even the earliest works in the collection sparkle away now on spotless walls.

Fesch collected very extensively. At one time his cache of Italian paintings was considered second in France only to that of the Louvre. Of course the clever old churchman took advantage of an excep- tionally favourable market in the years following the French Revolution. Indeed, his aim was to be able to illustrate the whole history of European painting, to this end buying Italian primitives, including works from the school of Rimini, when few others were interested. Bellini, Botticelli and the extraordinary Cosima Tura feature also, and Italian emphasis continues with such as Lorenzo di Credi, Pier Francesco Cittadini and Girolamo Forabosco as well as Titian and an attempted Veronese. A double portrait by Pietro Paolini (1603- 1681) reminded me oddly of Balthus, while Luca Giordano (1634-1705) also antedates the simpler drama of more modern styles. Clearly not all work at the museum is of outstanding quality or interest: looking at Corrado Giaquinto or some awful 17th- century Florentines one wonders just how keen the cardinal's eye, rather than ac- quisitive instinct, may have been.

While I realise few readers may be slipping over to Ajaccio simply to visit the museum, I should stress that the collection, along with the truly remarkable megalithic sites at Filitosa, Palaggiu and elsewhere, offer important cultural makeweights to the other attractions of an extraordinary island. For example, lovers of unusual moths and butterflies can have a field day in Corsica. Indeed, my own one regret concerned the sad paucity of songbirds or other avian life. I fear that in Corsica, as in so many other Mediterranean lands, too many birds are made to keep their best singing for the cooking pot.

Previous page

Previous page