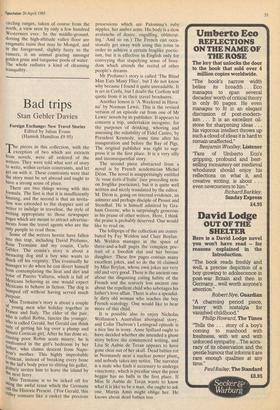

The high places

Andrew Robinson

Himalaya: Encounters with Eternity Ashvin Mehta (Thames & Hudson £20) Tibet Kevin Kling (Thames & Hudson £20) what is it exactly about the Himalaya that excites the imagination so much? Some years ago I worked in the low foothills below Simla, and I can never forget my first sight of the higher, but by no means highest snow ranges, far off, merging with the horizon, as seen from the verandah of a rather rickety hotel in Simla.

Perhaps one comes closest to an answer in two double-page spreads in Ashvin Mehta's book of photographs, which are very properly adjacent. The first shows three razor-sharp white peaks like vast broken teeth, the snow slipping off their lower reaches, etched against an atmos- phere of deep azure. Their lower part is entirely obscured by a billow of grey cloud. In the second, a different, more rounded, range is shown, bearing little snow but equally remote, with a miasma of drifting cloud discreetly veiling the whole picture, revealing only glimpses of gaunt rock. As anyone who has gone in search of high. mountains knows, this is the commoner view.

Yet the frequent disappointment is part of the lure; these high places are both inaccessible to the human foot and invisi- ble to the human eye. No wonder such mountains became personified by Man and acquired important religious significance as abodes of the Gods, which is of course how Hindus and Buddhists regard the high Himalaya. In an informative though slight- ly sententious introduction to the region, the climber Maurice Herzog, who was first up Annapurna in 1950, writes that the Himalaya 'is set high above the earth, like an altar. It is both a sanctuary to retreat to, and a holy place. There, God still exists.' Whether seen starkly from close-up, or • glistening magically from the foothills across miles of space, their very presence causes the mind to expand perceptibly, acquiring a kind of humility as it reaches out towards the inaccessible. This explains the special tranquillity of the famous hill- stations to which the Raj once escaped from the heat of the plains.

Mehta's book has the subtitle 'Encoun- ters with Eternity', and he shows full awareness of the risks which could so easily cause his work to degenerate into. vapid 'mystical' views of prettiness or rugged grandeur. As befits the subject, he sets his sights high: 'According to Indian philoso- phy, the five elements of earth, fire, water, wind and sky (or space) are the Gods who form the limits of the Formless. In this sense, my photography of nature and of Himalaya is an attempt to portray Him, and I have succeeded to the extent that I am able to capture the elements not merely as elements but as His limbs.'

Lest this seems to verge on high-falutin irrelevance, it is worth quoting Mehta's understanding of creativity in full, since it suggests the genuine simplicity of his approach to his monumental task: If one pauses to consider the process of creativity in an artist, the final creation can rarely evoke eternity unless one was in touch with it at the time of genesis. It matters, therefore, whether one looks upon the ele- ments as just elements or much more. A certain frame of mind can result in construc- tion, and another not a frame of mind but a state of communion — results in creation. All constructions are products of Time and vanish in Time, in spite of their glitter and apparent brilliance. The creations outlive Time and make both the viewer and the creator experience timelessness.

Notwithstanding a few photographs which are simply 'scenic', many of the photographs do exhibit this 'communion', and no description in words can catch their spirit. Some examples may nevertheless indicate the marvellous range of subject matter. The opening one shows sprays of almond blossom in spring floating above the intense green of the Kashmir Valley floor; behind and above, at an indefinable oceanic depth, rises the massif that sur- rounds the Vale, topped off with a little snow. Still in Kashmir, there is an asto- nishingly lovely scene of children playing beneath the autumn chenar trees, the great plane trees first planted by the Moghul emperors 500 years ago, where the filtered sunlight playing on the greens and browns reminds one of nothing so much as a beech woodland in the heart of England.

The glory must really belong to the views of the high Himalaya, though it is surpris- ing that Mount Kailas, mentioned by Her- zog, makes no appearance and sad that some of these could be better reproduced. Mehta manages to grasp on paper much of their alien, barren but also dramatic sweep, often by contrast with their gentler lower slopes. Everest makes one straight- forward entrance taken from on high, and then again in a final inspiring performance taken from a point two days' march from Darjeeling, where four of the highest peaks in the world stand revealed in luminous golden light, while the fore- ground is forbidding with half-perceived shadows.

Goldness, curiously enough, is a feature of the photographs in Tibet. of the land beyond the Himalaya: not just in the dramatic swathes of light and dark, but in the colour of vast stretches of mountain stubble, in the barley-fields waving below snow-capped peaks, and in the mounds of tough, rancid yak-butter on sale on the pavements of Lhasa. Where one expects mainly windswept grimness, one finds an austere smile, epitomised by the intriguing cover photograph showing harvest time which has an inescapable whiff of an Impressionist cornfield about it.

It became possible for foreigners to examine the face of Tibet again only in 1980 when China suddenly lifted some of its restrictions on entry. Kevin Kling, a young American photographer, had per- mission to accompany two French geolo- gical expeditions, allowing her to travel thousands of miles in remotest Tibet by road and track, staying in Chinese military camps and small Sino-Tibetan agricultural communities.

Most of Tibet is high plateau, about 15,000 feet in the north and about 13,000 in the south before rising up to the Hima- layan ranges. Through the middle, parallel to the Himalaya, flows the valley of the Tsangpo, which eventually curves back on itself in an enormous arc and debouches into the Bay of Bengal as the Brahmaput- ra. There is a surprising amount of water on this arid Tibetan plateau, with lakes of a forbiddingly chill blue, the colour of infin- ity in Tibetan art, and more inviting tanks that suggest Tibetans do have opportuni- ties to bathe after all.

Apart from the lamas, most people appear to survive on small-scale agriculture and the rearing of sheep and yaks, the bison-like, shaggy beasts that flourish only above 13,000 feet. They are apparently very difficult to mount, so mounted Tibe- tans are generally found on horses, like their Mongol forbears and the Bolivians they resemble ethnically, though yaks are vital beasts of burden for the caravanserais that track these wastes. They are also killed for meat — by Muslim butchers, since Tibetans abhor the taking of life — and their dung is the staple fuel of Tibetan cooking and heating. Yak butter is rubbed on the face to avoid dryness and sunburn, but unfortunately Kling's introduction does not reveal if it is this that brings out the peach-like russet blush on almost every Tibetan cheek.

The introduction is a little disappointing in two important respects. It raises interest in aspects of Tibetan life, which the photo- graphs do not always fulfil, for example, 'funeral rites or tea-making. And it lacks much historical perspective. More is needed on the growth of Buddhism and the real nature of Tibetan feudalism, and, in more recent times, the Chinese invasion in 1950, the Dalai Lama's flight to India and the subsequent oppression of Tibetans and destruction of art objects. And surely Younghusband's famous, indeed notorious mission to Lhasa in 1904 deserves at least a mention?

The strengths of this informative, often beautiful yet ultimately not mysterious book lie in its big landscapes, particularly those looking across miles of flat terrain leading to distant peaks; these have the ethereal quality one expects of the 'roof of the world'. One of the finest is a magnifi- cent double-page spread of a distant but not remote Everest and its attendant en- circling ranges, taken of course from the north, a view seen by only a few hundred Westerners ever. In the middle-ground, dotting the high-altitude valley floor are enigmatic ruins that may be Mongol, and in the foreground, slightly fuzzy to the camera, is an animal grazing amongst golden grass and turquoise pools of water. The whole radiates a kind of cleansing tranquility.

Previous page

Previous page