Exhibitions

Picabia (Royal Scottish Academy, till 4 September) Lucian Freud (Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, till 7 October) Joan Eardley Retrospective (Talbot Rice Gallery, till 10 September) James Morrison (Scottish Gallery, till 6 September) Reflections of Venice (Calton Gallery, till 5 September)

Natural reactions

Giles Auty

0 ne can learn something new about human nature almost any day, often through unlikely circumstances. When I was connected finally with the British Rail office in London which deals with sleeping car reservations to Edinburgh, I remarked, more in hysterical disbelief than in anger, that it had taken 25 minutes for anyone to answer the telephone. 'That's nothing, sir,' my respondent told me cheerfully, `callers sometimes wait two hours or so.' To sit, telephone in hand, like the proverbial citrus for the time it would take to count to 10,000 or so — without the benefit even of the occasional, encouraging 'calls will be dealt with in strict rotation' or any similar palliative — strikes me as an act of superhuman self-abnegation for which one could prepare oneself only by lengthy residence on the Indian sub-continent.

In my view, the natural reaction to such treatment by British Rail is to fly to Edinburgh then and in the future even if this may, at times, be less convenient. The abandonment of natural behaviour is insi- dious in its dangers. I do not pretend to understand those who can cradle an un- answering telephone receiver for a full two hours, though probably they harm none but themselves. But other, equally unnatu- ral behaviour can have more far-reaching consequences: the supposedly 'liberal' non-upbringing of children in the Sixties, for instance, or passionate and inexplicable advocacy of ugly and vacuous vanguardist art.

It may surprise few to learn that I am no great protagonist of Dada or any of the other anti-art movements which followed in its wake. Their purposes seem to me to have much in common with a desire to pull faces at any we deem middle-class or conventional. There might be some child- ish satisfaction to be derived from this but are any of us less worthy of ridicule ourselves?

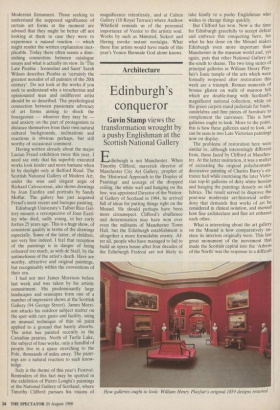

The Royal Scottish Academy puts on Picabia 1879-1953 and The Magic Mirror : Dada and Surrealism from a private collec- tion as this year's Edinburgh Festival offer- ing. The received modernist wisdom used to be that Picabia's ugly, boring and would-be-shocking early art was the pinna- cle of his achievement, from which he sharply and sadly declined. The new 'wis- dom' emanating from those no less unwill- ing than their predecessors to trust the judgment of their eyes, is that Picabia's ugly, boring and would-be-shocking late art is of the greater worth because it anticipated the ugly, boring etc. art pro- duced by Polke, Schnabel and other stars of the currently fashionable post- Lucian Freud's most recent painting, 'Two Men', 1987-88, which has just been acquired by the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Modernist firmament. Those seeking to understand the supposed significance of certain art forms at the moment are advised that they might be better off not looking at them in case they were to experience a natural reaction — which might render the written explanation inex- plicable. Today there often seems a dimi- nishing connection between catalogue essays and what is actually on view. In 'The Late Picabia : Iconoclast and Saint' Sarah Wilson describes Picabia as 'certainly the greatest moralist of all painters of the 20th century'. Do not look at the works if you seek to understand why a treacherous and opinionated man and indifferent artist should be so described. The psychological connection between passionate advocacy of art forms aiming to shock the bourgeoisie — whoever they may be and anxiety on the part of protagonists to distance themselves from their own natural cultural backgrounds, inclinations and reactions is obvious perhaps, but still worthy of occasional comment.

Having written already about the major Lucian Freud exhibition twice this year, I need say only that his superbly executed works look kinder and more humane when lit by daylight only at Belford Road. The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, under the wise and elegant aegis of Richard Calvocoressi, also shows drawings by Joan Eardley and portraits by Sandy Moffat. The gallery has just acquired Freud's most recent and baroque painting.

Edinburgh University's Talbot Rice Gal- lery mounts a retrospective of Joan Eard- ley who died, sadly young, in her early forties 25 years ago. This is a huge show, of consistent quality in terms of the drawings especially. Some of the latter, of children, are very fine indeed. I feel that reception of the paintings is in danger of being coloured too much, as with de Stael, by the untimeliness of the artist's death. Here are worthy, attractive and original paintings, but recognisably within the conventions of their era.

I had not met James Morrison before last week and was taken by his artistic commitment. His predominantly large landscapes and seascapes form one of a number of impressive shows at the Scottish Gallery (94 George Street). James Morri- son attacks his outdoor subject matter on the spot with rare gusto and facility, using an unusual technique of thin oil paint applied to a ground that barely absorbs. The artist has painted recently in the Canadian prairies. North of Turtle Lake, the subject of four works, only a handful of people live in a space stretching to the Pole, thousands of miles away. The paint- ings are a natural reaction to such know- ledge.

Italy is the theme of this year's Festival. Reminders of this fact may be spotted in the exhibition of Pietro Longhi's paintings at the National Gallery of Scotland, where Timothy Clifford pursues his visions of magnificence relentlessly, and at Calton Gallery (10 Royal Terrace) where Andrew Whitfield reminds us of the perennial importance of Venice to the artistic soul. Works by such as Monsted, Sickert and Hering invoke instant nostalgia. What these fine artists would have made of this year's Venice Biennale God alone knows.

Previous page

Previous page