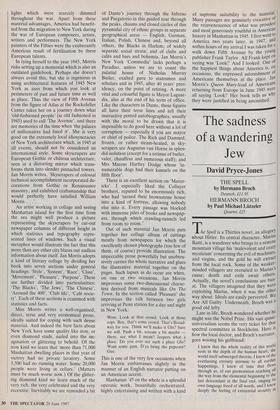

When Johnny came sailing home again

Stephen Spender

MANHATTAN '45 by Jan Morris Faber, £12.50 Manhattan '45 opens almost Whit- manesquely with a splendid prologue re- calling the arrival of the British liner the Queen Mary, painted a battleship grey, in the harbour of New York, on 20 June 1945. The passengers are 14,526 American ser- vicemen and women back from the war in Europe. They are given one of the 'historic occasion' welcomes for which that city is famous:

When she entered the wide expanse of New York Bay, treading easily towards the city with only a gentle sliver of steam from her funnels, flottillas of lesser vessels came out to greet her, milled about her passage or hastily got out of her way — a couple of aircraft- carriers, many tugs, freighters, tall-funnelled ferryboats, sludge barges, train-flats, laun- ches and lighters of every kind, the 16-knot fireboat, the Fire-fighter, most powerful in the world, enthusiastically spouting out its water plumes.

Manhattan '45 is the evocation of one triumphal year which Jan Morris sees as the culminating point in New York's his- tory. Everything before leads up to 1945 and most things after belong to its decline. History acts as a good stage-manager in supporting this view by contrasting the vitality, the prosperity, the youth of New York in that year with the poverty, the exhaustion, the wretchedness of Europe still war-wrecked, ruinous and on rations. Morris makes much of the gargantuan luminosity of the New York skyscrapers, lights which were scarcely dimmed throughout the war. Apart from these material advantages, America had benefit- ted from the migration to New York during the war of European composers, artists, writers and performers. The New York painters of the Fifties were the exuberantly American result of fertilisation by these European talents.

In tying herself to the year 1945, Morris risks setting up a memorial which is also an outdated guidebook. Perhaps she doesn't always avoid this, but she is ingenious in using architectural features of 1945 New York as axes from which you look at perimeters of past and future time as well as place. Thus the view of Fifth Avenue from the figure of Atlas at the Rockefeller Center takes her on a journey down what `old-fashioned people' (ie old fashioned in 1945) used to call 'The Avenue', and there are memories of the time when 'the palaces of millionaires had lined it'. She is very good on the extremely local idiosyncracies of New York architecture which, in 1945 at all events, should not be considered an international style. Some skyscrapers are European Gothic or château architecture, seen in a distorting mirror which trans- forms them into slender pinnacled towers. Jan Morris writes, 'Skyscrapers of colossal technical accomplishment incorporated de- corations from Gothic or Renaissance masonry, and exhibited craftsmanship that would perfectly have satisfied William Morris . .

An artist working in collage and seeing Manhattan island for the first time from the sea might well produce a picture representing the skyscrapers by cut-out newspaper columns of different height in which statistics and typography repre- sented lines of windows. Such a visual metaphor would illustrate the fact that this more than any other city blares out endless information about itself. Jan Morris adopts a kind of literary collage by dividing her book into seven sections under general headings: 'Style', 'System', 'Race', 'Class', `Movement', 'Pleasure', 'Purpose'. These are further divided into particularities: `The Blacks', 'The Jews', 'The Chinese', `Around the 400', 'Club life', 'Café socie- ty'. Each of these sections is crammed with statistics and facts.

Miss Morris writes a well-organised, direct, terse and very economical prose, ideally suited for coping with such dense material. And indeed the bare facts about New York have some quality like iron, or even diamond studs, nailed into the im- agination or glittering to behold. Of the iron kind we learn that 'more than 71,000 Manhattan dwelling places in that year of victory had no private lavatory. Some 3,500 had no running water. Some 20,000 people were living in cellars.' (Matters must be much worse now.) Of the glitter- ing diamond kind we learn much of the very rich, the very celebrated and the very eccentric. Inevitably we are reminded a bit of Dante's journey through the Inferno and Purgatorio in this guided tour through the peaks, chasms and closed circles of this pyramidal city of ethnic groups in separate geographical areas — English, German, Italian, Polish, Chinese and, beyond all others, the Blacks in Harlem; of widely separate social strata; and of clubs and cafés and bars and bohemia. Jan Morris's New York `Commedia' lacks perhaps a Paradiso, unless we are to count the palatial house of Nicholas Murray Butler, exalted guru to statesmen and scholars and in 1945, after 40 years' pres- idency, on the point of retiring. A more vital and colourful figure is Mayor Laguar- dia, also at the end of his term of office. Like the characters in Dante, these figures all have their terse lines and tell their instructive potted autobiographies, usually with the moral to be drawn that it is impossible to do good here without a lot of corruption — especially if you are mayor or chief of police. The Rich and Damned, frozen, or rather steam-heated, in sky- scrapers are Augustus van Horne in splen- did isolation (except for a retinue of butler, valet, chauffeur and numerous staff); and Mrs Marcus Hartley Dodge whose 'in- numerable dogs had their kennels on the fifth floor'.

There is an excellent section on 'Maver- icks'. I especially liked the Colluyer brothers, reputed to be enormously rich, who had 'turned their brownstone house into a kind of fortress, allowing nobody else into it. Every passage was blocked with immense piles of books and newspap- ers, through which crawling-tunnels led from room to room.'

Out of such material Jan Morris puts together her collage album of cuttings mostly from newspapers for which the excellently chosen photographs (too few of them, of course) provide illustration. The impeccable prose powerfully but unobtru- sively carries the whole narrative and glues the illustrative material together on the pages. Such lapses as do occur are when, on one or two occasions, Jan Morris improvises some two-dimensional charac- ters derived from musicals like On The Town. In the section called 'Pleasure' she improvises the talk between two girls arriving at Penn station for a day and night in New York: Wow. Look at that crowd. Look at those cops. Boy, that's some crowd. That's Broad- way for you. Think we'll make it Glo? Sure we will. Push a bit, scream a bit maybe there, see what I mean? Jeepers what a place. Do you ever see such a place Glo? Want some gum. D'ya bring the popcorn? Gee.

This is one of the very few occasions when Jan Morris embarrasses slightly in the manner of an English narrator putting on an American accent.

Manhattan '45 on the whole is a splendid operatic work, beautifully orchestrated, highly entertaining and written with a kind of supreme suitability to the material. Many passages are genuinely evocative of the rejuvenescence of what was proudest and most generously youthful in American history in Manhattan in 1945. I first went to America two years later, in 1947, and within hours of my arrival I was taken for a walk down Fifth Avenue by the young publisher Frank Taylor. All Frank kept on saying was 'Look!' And I looked. One of the happiest things about America is, on occasions, the expressed astonishment of Americans themselves at the place. Jan Morris's Queen Mary-load of Americans returning from Europe in June 1945 were all saying 'Look!' Her book tells us why they were justified in being astonished.

Previous page

Previous page